Bergman and Sweden

The relationship between Bergman and his country of birth was a complex affair.

'I cannot imagine myself working somewhere else than in Sweden.' 'Now I leave Sweden!'Ingmar Bergman in 1960 and 1976, respectively

Bergman och Sverige

In fact, the relationship was not entirely unlike one of thosefraught marriages of his films: an explosive mixture of attraction and antagonism. In this essay, we'll look into the matter more deeply.

During the filming of Virgin Spring Bergman wrote a short piece published in English under the title A Page from my Diary, as part of the press pack for the international launch of the film. In it he tells the story of one rainy spring morning in 1959: "All were active in order to keep warm. The temperature was about freezing point, and now and then snowflakes appeared from the ice-grey mist."

The crew struggled to get the ageing camera equipment working in the harsh weather, when suddenly the clouds parted and the sun shone through. Time for a take. "But when the rays of the sun penetrated and sparkled across the mysterious darkness of this water in the forest, and through the transparent spring greenery of the Swedish birch trees, someone called out loudly and pointed to the sky."

Two cranes were flying majestically over the treetops. Everyone stopped working to admire the scene. When the birds had disappeared, Bergman mused for a moment over how pleasant it would be to have a Hollywood-like setup at his disposal:

to have a camera track that isn't buckled, a camera truck that doesn't creak, and it would be quite an event for once to make a motion picture with a budget of over two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, just for the experience. Yet despite all that I'm saying a straight no to the proposition of America. I felt a sudden happiness and relief. I felt secure and at home.

At this point in his career Bergman was indeed turning down a number of international offers on the grounds of his deep affinity with his homeland. He also doubted his abilities to make a film in a language other than his native Swedish. This attachment to Sweden did not, however, win him universal praise in his home country, far from it. Always a favourite subject for debate, he did indeed have some champions, but his detractors were becoming more vehement than ever. Olof Lagercrantz, the influential editor of the Swedish broadsheet Dagens Nyheter, concluded his review of Smiles of a Summer Nightwith the following laconic remark: "I am ashamed to have seen it." (Lagercrantz would later claim that his venomous attitude to Bergman was largely due to his own middle class upbringing: he felt too close, quite simply, to the things that Bergman was portraying.) And one critic wrote of Sawdust and Tinsel that he refused to "perform an ocular inspection of Mr Bergman's vomit."

Our Dala Horse to the World

In 1960, Bo Widerberg, who after Bergman is Sweden's most successful film director since the silent film era, wrote a pamphlet containing a number of accusations against Bergman, one of which was stagnation:

What one expects with growing impatience from this brilliant technician and director of actors is for him to move on, to grow tired of his role as our Dala horse to the world. All we expect of a Dala horse is that it should look like a Dala horse, and satisfying that demand would probably mean death for any artist in the long run.

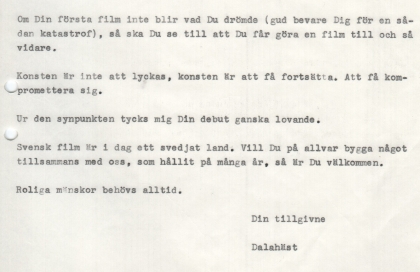

Dala horses in the stable.

Widerberg's now famous attack attracted considerable attention both in Sweden and abroad. Less well known is the fact that Bergman actually replied to Widerberg in a private letter (now in the Ingmar Bergman Archives). Courteous and encouraging (albeit somewhat patronising), the letter is signed: "Your devoted Dala horse".

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

Yet perhaps the most widespread coverage of Bergman centred on his alleged demonism demoni and his reputation as a ladies' man kvinnokarl who was obsessed with seducing his actresses. In a fascinating article on Bergman's image in Sweden, Maaret Koskinen observes:

Outside Sweden Ingmar Bergman is almost exclusively associated with the elitist world of high culture. So it always comes as something of a surprise if one points out that here in Sweden he has also been associated with the other end of the scale: popular culture, an obsessive interest in his personality and his cult celebrity status. If one takes the popular press – film and women's magazines, the tabloids – a picture emerges which is as entertaining as it is depressingly clear: Ingmar Bergman and (gossip about) his private life have constituted a veritable public soap opera, so persistent and long-lasting that it can only really be compared with the attention which nowadays is bestowed solely on film stars and royalty.

Go, Bergman!

During the 1960s and 70s Sweden's cultural climate became conspicuously politicised (in a radical, left-wing sense). Bergman was accused of being a fossil, a highbrow, and worst of all, a bourgeois. His artistic production did not suffer especially, apart from some disruption to the shooting of A Passion. Bergman's prime audience lay abroad, and was large enough to provide well for him. Yet he appears bitter about Sweden's left wing uprisings of 1968, "our provincial cultural revolution" as he calls it, which carried with it the demand that: "Dramaten should be burnt to the ground himself and Sjöberg and Bergman should be hanged from the Tornberg clock outsido in Nybroplan". The passage, from The Magic Lantern, continues:

It is possible some brave researcher will one day investigate just how much damage was done to our cultural life by 1968 movement. It is possible, but hardly likely. Today, frustrated revolutionaries still cling to their desks in editorial offices and talk bitterly about 'the renewal that stopped short'. They do not see (and how could they!) that their contribuition was a deadly slashing blow at an evolution that must be never separated from its roots.

The somewhat vexed relationship between Ingmar Bergman and Sweden came to a head in 1976, when he was arrested by the police in the middle of a rehearsal at the Royal Dramatic Theatre and accused of tax evasion. It turned out that he was innocent (the inquiries were soon dropped), but in the public consciousness he cut a tainted figure. Bergman suffered a nervous breakdown, and after a short stay in hospital he fled the country with newspaper headlines such as "Go, Bergman, we won't miss you" ringing in his ears. Despite cranes flying over treetops, Bergman finally felt obliged to terminate his relationship with Sweden. Yet after six years of voluntary exile in Germany, he returned to his homeland in 1982.

Regardless of Bergman's fluctuating fortunes in his homeland, he has been a major Swedish 'brand' ever since his international breakthrough in the 1950s. Ingmar Bergman is just as much a symbol of Sweden as Volvo, IKEA, Björn Borg or ABBA.

In his critical article, Bo Widerberg also claimed that you need to be a foreigner in order to appreciate Bergman, or at least to appreciate his dialogue: "I wonder to what extent Bergman's foreign language translators have a hand in his success, and whether people quite simply speak less strangely in the American versions of his films."

Whatever the reason, attitudes to Bergman outside Sweden, especially in the USA, have bordered on the adulatory. And this is probably not entirely due to the quality of his films. Scandinavian exoticism, scantily-clad, outspoken women and the odd helping of fashionable pessimism are equally important factors. Rightly or wrongly, Bergman has, in essence, become synonymous with a certain international view of Sweden.

Savouring the prospect of Bergman retrospective in New York in 2004, the New Yorker magazine's film critic wrote.

There is no mistaking the look of a Bergman picture, or even the sound of it. Close your eyes, or avert them from the subtitles, and you find yourself swept up afresh in the sway of his dialogue. It may be unintelligible, but, like the libretto of an opera in an unfamiliar tongue, it makes a mysterious music of its own, and the blend of clucking and lulling in the Swedish voice seems wonderfully apt to Bergman's mood.

Anguish is my inheritance

In Woody Allen's Manhattan (1979), Diane Keaton's character Mary wants to put Ingmar Bergman in her "Academy of the Overrated". The main character, Alvy (played by Allen himself) protests: "Bergman? Bergman is the only genius in cinema today, I think." To which Mary replies:

God, you're so the opposite, I mean you write that absolutely fabulous television show, it's brilliantly funny and his view is so Scandinavian, it's bleak, I mean all that Kierkegaard, right? It's really adolescent, you know, fashionable pessimism, I mean The Silence, God's silence, OK, OK, OK, I mean I loved it when I was a graduate but I mean alright, you outgrow it, you absolutely outgrow it!

"All that Kierkegaard", together with Scandinavia's cultural heritage (Pär Lagerkvist's lines "Anguish, anguish is my inheritance", Edvard Munch's painting "The Scream", etc.) seems for many to sum up the Nordic temperament. Films by Bergman or, for that matter, the Finnish Kaurismäki brothers have no doubt played a part in this. That a philosopher like Schopenhauer makes Kierkegaard seem quite a cheerful chap, or that films by Todd Solondz make Bergman seem like an optimist, does not seem to have registered: the Germans and Americans are not universally regarded as a gloomy bunch. Rightly or wrongly, the Scandinavians find it hard to escape their image as potential suicide victims.

Edvard Munch, Skriet (1893). Image cropped.

These and other myths have been taken so seriously that Sweden's official website, feels obliged to tackle them head on, insisting that Sweden is down at the bottom of international statistics tables for suicide, sexually transmitted diseases and teenage pregnancies. And that thanks to the Gulf Stream, Swedish summers can be very pleasant indeed.

Swedish Sin

Of all these "myths" the notion of Swedish sin has been a particularly important component in Ingmar Bergman's international popularity. Swedish films of the 1950s and 60s set the bandwagon in motion. Arne Mattson's One Summer of Happiness (1951) contained a naked bathing scene which in its own right made the film an international success. Other films followed, including works by Ingmar Bergman. Summer with Monika, The Virgin Springand The Silence were all the subject of intense censorship debates, and their success outside Sweden cannot entirely be put down to their artistic qualities. Swedish sin on celluloid reached new heights (plumbed new depths?) with two New Wave-inspired films by Vilgot Sjöman, I am Curious – Yellow (1967) and I am Curious – Blue (1968) (yellow and blue being the colours of the Swedish flag). Both films contained explicit sex scenes within a sophisticated meta-cinematic framework. The first of the two is still reported as being the most popular foreign film ever in the USA, yet this is probably due less to its modernist style than to a few short scenes of nudity.

'Filmed in Sweden' probably said it all...

Despite their obviously serious subject matter, Ingmar Bergman's films have undoubtedly benefited from these associations, especially in terms of international marketing. In America some of Bergman's films were promoted with dubious titles that had little or nothing to do with the films' content, or indeed their original titles. Thus Summer Interludebecame "Illicit Interlude" and Summer with Monica became "Monika – The Story of a Bad Girl". Bergman himself appeared to play along. In a programme notefor the latter film he insisted, albeit not entirely without irony, that naked bathing should be compulsory in all Swedish films:

In a country whose climate seldom gives rise to anything other that hot baths, ice baths or saunas more than possibly once or twice a year, we should, through the agency of film, maintain the illusion that there exists an idyllic clime where shapely young girls splash around as God has created them without getting goose pimples right down to their very toes.

Finally, the American advertisements for two of Bergman's most demanding and uncompromising films speak for themselves. One ad for Persona quotes a review of the film from the New York Post: "Ingmar Bergman has followed the Swedish freedom into the exploration of sex". And the distributors of The Silence must also have been grateful to the New York Post for its review of that particular film, from which they quoted: "Bergman at his most powerful! A sexual frankness that blazes a new trail."

Accordingly, it is hardly surprising that the German and French expressions 'Schwedenfilm' and 'films suédoises' still remain synonymous with pornographic films, or that the US distribution company, Swedish Erotica, has nothing whatsoever to do with Sweden.

Sources

- Ingmar Bergman Archives

- Ingmar Bergman, "Ingmar Bergman intervjuar sig själv inför premiären på 'Sommaren med Monika'"

- Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern

- Birgitta Steene, Ingmar Bergman: A Guide to References and Resources

- Maaret Koskinen, "Från erotisk ikon till klanhövding", Dagens Nyheter, 2 januari, 2004.

- Anthony Lane, “Smorgasbord: An Ingmar Bergman retrospective”, The New Yorker, 14 juni, 2004.

- Bo Widerberg, Visionen i svensk film (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 1962).

- Svensk Filmdatabas

- www.sweden.se