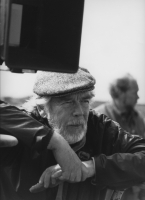

Victor Sjöström

Director, actor, scriptwriter and cultural personality, Sjöström was one of the most prominent Swedish film and theatre personalities of the 20th century and a constant source of inspiration for Ingmar Bergman.

Victor Sjöström

Director, actor, scriptwriter and cultural personality, Sjöström was one of the most prominent Swedish film and theatre personalities of the 20th century and a constant source of inspiration for Ingmar Bergman.

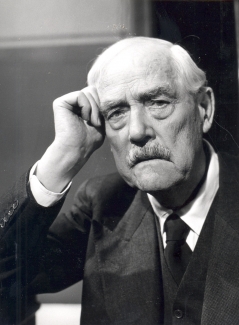

'Never before or since have I experienced a face so noble and enlightened. And yet this was nothing more than a piece of acting in a dirty studio.'

Bergman on Sjöström's performance in Wild Strawberries

About Sjöström

Born Viktor David Sjöström on 20 September 1879 in Värmland in the west of Sweden, Sjöström emigrated with his family to America (Brooklyn, New York) in 1880 where his father, Olof, who had struggled in Sweden, built up a successful shipping agency in New York. His mother, Elisabeth, a former regional theatre actress and sister of Victor Hartman of Royal Dramatic Theatre fame, died of puerperal fever in 1886, and his father subsequently married a younger woman who had previously been the family nanny. Victor had a strained relationship with his stepmother and this, alongside his father's growing religious austerity, caused the somewhat unruly Victor to be sent home alone to Sweden in 1893 to live with his aunt in Uppsala.

During his school holidays he visited his uncle, who would take him to the Royal Dramatic Theatre. As a teenager Victor developed a passionate interest in theatre, becoming the director of the Uppsala Sports Club drama section, and also its leading actor. In 1895 his father returned to Sweden and Stockholm, and Victor moved back in with his immediate family. This meant he had to break off his studies and take a job to help his father, who was once again in difficult financial straits. One of his first jobs was selling doughnuts (recently invented and highly fashionable) on the streets of Stockholm.

In 1896 Olof Sjöström died, and Victor decided to become an actor full time. Lacking the necessary funds to study at the Royal Dramatic Theatre drama school, he managed to get a job with a touring theatre company. Up until 1912 he travelled around Sweden and Finland as an itinerant actor and an increasingly successful director.

In February 1912 Sjöström was contacted by the first Swedish film producer of any significance, Charles Magnusson (1878-1948), who gave him the job of senior director at his production company Svenska Bio. There, Victor got to know Mauritz Stiller, who was also to achieve great fame as a silent film director. He also met the cameramen Henrik and Julius Jaenzon, who later worked both for Sjöström and for Stiller. To learn this new craft, Sjöström first acted in a Stiller film, yet soon made his directing debut with The Gardener in 1912. In this film, banned by the censors in its native Sweden, Sjöström played the title role alongside his second wife, Lili Beck, and Gösta Ekman (the father of Hasse Ekman).

Sjöström gained recognition as a filmmaker the following year with the social realism of Ingeborg Holm. The film created quite a stir in Sweden, both as a work of art but also as a comment on poverty. Ingeborg Holm was also a major international success. However, many of Victor Sjöström's early films were run-of-the-mill melodramas which have not survived.

Sjöström rose to prominence in the years from 1916 to 1918, which marked the start of the Golden Age of Swedish cinema, which stretches from Sjöström's A Man There Was to Stiller's Gösta Bergling's Saga. A Man There Was, starring Sjöström's third wife Edith Erastoff, and The Outlaw and His Wife, firmly established Sjöström's reputation with their 'depictions of nature, the interplay between man and nature, its lighting, photography and the sensitivity and sincerity of their character portrayals'. The latter is often regarded as a cinematic milestone. Both films were partly shot under difficult conditions in Stockholm's outer archipelago and the Abisko national park.

A Man There Was won the acclaim of Selma Lagerlöf, who gave her permission for Sjöström to make a film version of The Girl from the Marsh Croft, the first of his five adaptations of her works.

In 1919 Svenska Bio, where Sjöström had been employed since 1912, merged with Filmindustri AB Skandia to form a new company, Svensk Filmindustri. A year later the new studios at Råsunda, just outside Stockholm, were completed. The first project for the new company was Victor Sjöström's magnum opus The Phantom Carriage, based on Selma Lagerlöf's 1912 novel. Although not regarded as one of Lagerlöf's best works, the novel's theme of conversion and moral struggle fascinated Sjöström. and the supernatural elements has a special appeal to the cinematographer Julius Jaenzon, who relished the chance to experiment with special effects. In technical terms the film set new standards and was an all-round success. Ingmar Bergman regularly watched The Phantom Carriage every summer at his private cinema on Fårö:

My relationship with The Phantom Carriage is very special. I was 15 years old when I saw it for the first time. [... ] I remember it as one of the major emotional and artistic experiences of my life.

In 1923 Sjöström was invited to Hollywood, where he worked with Louis B Mayer and Irving Thalberg. The first major director to be employed by the newly-formed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio, Sjöström, unlike many some other Swedes who tried their luck in Hollywood, including Mauritz Stiller and Hjalmar Bergman, enjoyed both major commercial and artistic success. In 1928 Mauritz Stiller died in Stockholm, and Victor Sjöström visited him on his death bed. This was one of the events that prompted Sjöström and his family, which now comprised his wife Edith and two daughters, to move back to Sweden in 1930. Following his return, he only directed two more films, neither of which was a particular success. He did, however, make a number of films in front of the camera, and he also returned to the stage.

Between 1939 and 1943 Sjöström worked almost exclusively in the theatre, but in 1942–43 he was called back to Svensk Filmindustri by the new head of the company Carl Anders Dymling, as artistic director responsible for all film production. In this role he was inspired by Irving Thalberg, becoming heavily involved in screen writing ('If you've got a good screenplay you can assume that any film is 75 per cent home and dry') and to a certain extent in editing, but he stayed away from the actual film shoots. During this period he first came into contact with Ingmar Bergman, who was working in the company's script department. He steered Bergman's first screenplay Torment through to production, and when Bergman himself got to direct Crisis, Sjöström was the young director's only ally in a company in which Bergman made himself so unpopular that he ended up getting the sack.

In 1945 his wife Edith died, and four years later Sjöström left Svensk Filmindustri. He played only a handful of film roles during this period, the most notable of which was as the ageing orchestra leader in Bergman's To Joy.

In the 1950s Victor Sjöström went back to his life in travelling theatre. His roles included Willy Loman in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, the title role in Swedenhielms (Max von Sydow played one of the sons when Sjöström made a guest appearance at the Helsingborg City Theatre), his last part being the title role in Johan Ulfstjerna (1957–1958).

In 1957 Ingmar Bergman repaid his indebtedness to Sjöström by giving him the main part in Wild Strawberries, which alongside The Phantom Carriage is the for film which Sjöström is best remembered. Bergman adapted the role specially for the great man, whose first inclination was to decline a part he thought too difficult to play. Yet Bergman prevailed:

Victor was in a bad mood, saying, 'I don't want to do this, I don't think you're right'. We clashed because I wanted Victor to do certain things that he didn't want to do, or rather he was tense and wanting to do too much and I didn't want him to do anything at all. But then he was amazing to work with as long as he was home by quarter past five sharp in time for his daily whisky.

During the filming Ingmar Bergman gave an 18-year old director's assistant the sole task of looking after Victor. This 18-year old was Hasse Ekman's son Gösta Ekman, grandson of the very Gösta Ekman who played Sjöström's son on his debut in The Gardener in 1912.

Just one day after the premiere of Wild Strawberries, Victor Sjöström was taken ill and rushed to hospital in Stockholm with heart trouble. During the course of 1959 his general condition declined and by December he was once again in hospital. Three weeks later he suffered from a blood clot and died on the evening of 3 January 1960.

Following Sjöström's death, Ingmar Bergman read out the following extract from the diary he kept during the filming of Wild Strawberries at a memorial ceremony organised by the Swedish Film Academy on 20 February 1960:

We had just shot the final scenes to round off Wild Strawberries [Smultronstället] the final close-ups of Isak Borg when he feels the sense of clarity and reconciliation. His face became illuminated with an enigmatic light, reflected from another reality. His facial expressions suddenly became mild, almost serene. His expression was open, smiling, full of love. . .

It was a miracle. . .

Such total tranquillity; a soul that had found peace and lucidity. Never before or since have I experienced a face so noble and enlightened. And yet this was nothing more than a piece of acting in a dirty studio. And it had to be acting. This exceedingly shy human creature would never have shown us bystanders this deeply buried treasure of compassion and purity had it not involved of a piece of acting, a performance .

Sources

- Ingmar Bergman, 20th Century of Bergman, editor Gunnar Bergdahl, (Göteborg: Göteborg Film Festival, 2000).

- Bengt Forslund, Victor Sjöström: his life and his work, translated by Peter Cowie with the assistance of Anna-Maija Marttinen and Christer Frunck, (New York: New York Zoetrope, 1988).