A matter of principle

[Update 12 June: upon publication of this post yesterday, a paragraph was missing, rendering the whole business with the rubbish bin below incomprehensible. Sorry about that.]

Now that this blog has been up and running for quite a while, it’s high time to inject a bit of formality into it. After numerous posts on look-a-likes and the outfit of the day, you rightfully deserve something a bit more substantial every now and again. Well then. As this is an archive blog, let us speak of archival matters. The lesson of the day: What is the principle of provenance?

If you’ve ever watched the Antiques Roadshow, then you know all about provenance, as regards previous ownership. For example:

This rubbish bin may not look like all that much, but it did belong to Ingmar Bergman and was therefore sold at auction for 22,000 crowns (2,500 euros), with the starting bid at 300–400 crowns (30–40 euros).

The principle of provenance (Fr. respect des fonds) is a bit more up-market when it comes to the archive branch, stating that an archive shall retain the articles and intentions of the original archivist.

In order to understand why this principle came about, we head back to the year 1194, when Philip II Augustus of France, upon returning from various plundering escapades, was ambushed by Richard I of England. Nowhere in all the schoolbooks of my childhood do I remember Richard the Lionheart as being so nasty, but the fact of the matter is that during this ambush, his soldiers ran off with not only all the loot that the French king had just laboriously stolen, but also the tax register and royal seal as well.

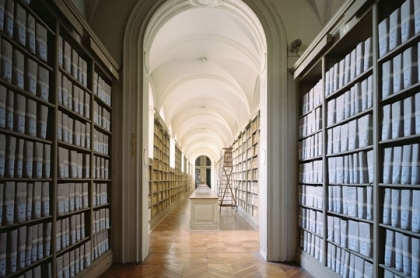

Philip II (probably not him, but more likely our ancient archive servicemen colleagues) had no choice but to rebuild the monarchy’s registers. This is a task one does not wish to undertake very often, and so the king decided to establish a central register containing his public records. This task was assigned to the monk Brother Guérin, who established Le Trésor des Chartes in 1195, the first proper archive system in the French kingdom. The archive maintained its name even when it was moved from Chartres to the Louvre, and on to La Sainte-Chapelle, where Louis IX already housed his prized relics including Christ’s Crown of Thorns. Difficult to imagine better company for any archived item.

The French National Archives fared rather well for a few hundred years, until events at the end of the 18th century shook the shelves at La Sainte-Chapelle, unsettling the dusty back catalogues. As is common knowledge, many things came to pass during the French Revolution, yet for those of us in the industry perhaps the greatest achievement was the establishment of the Archives Nationales in 1790. All private and public archives throughout the country (besides various smaller Le Trésor des Chartes’ document collections held by different political bodies, monasteries and country seats) were merged into one giant national archive.

To unify all these different collections, to sort and catalogue them according to varying guidelines, was presumably no simple task. After half a century of the, albeit, downright turbulent times of the republic–Reign of Terror–empire–monarchy, the poor archivists got fed up with cleaning up after the mess. In 1841, under the so-called July Monarchy, a commission of historians was founded, who established that the unity of the archive took precedence over the material objects.

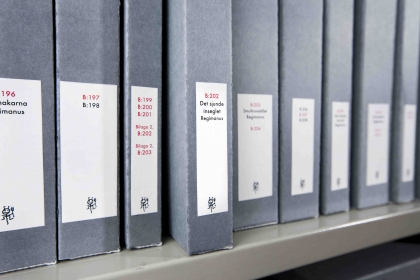

The principle of provenance was founded. The belief is that even when an archive changes owners, it should in principle appear the same. Say that an authority has an archive, grows tired of it and grants ownership of it to the National Archives. According to the principle of provenance, the National Archives must maintain the archive in the same order as established by the original archivist.

Ingmar Bergman established the Ingmar Bergman Archives. We have sorted, classified, catalogued and digitised the collection, but it is still in its original form. We occasionally acquire new objects, but these are not added to the Ingmar Bergman Archives (except in a few cases, depending on the type and provenance of the article) but rather construct their own small archival territories within our archives. The word ‘archive’ has two meanings: the actual physical place, building, institution in which the collection is stored; and the actual objects from the original archivist’s collection. Ingmar Bergman’s archives (the materials he accumulated and collected) are stored in the Ingmar Bergman Archives (owned by the Ingmar Bergman Foundation).

For example, we have letters from Käbi Laretei and Liv Ullmann, sketches and models made by Göran Wassberg – these are not part of the Ingmar Bergman Archives, even though they are stored in the Ingmar Bergman Archives. This is all in accordance with the principle of provenance. Because of this guiding principle, the archive itself is fairly indifferent regarding its collection. In other words, those of us who work in the archive may have our favourite pieces, but we have no say when it comes to what is perhaps requested by visitors and researchers or considered valuable from a financial or culture-historical perspective, as compared to those items which no one ever requests nor are considered to be of any research or public worth whatsoever. If the original archivist placed an object in the collection, so shall it remain.

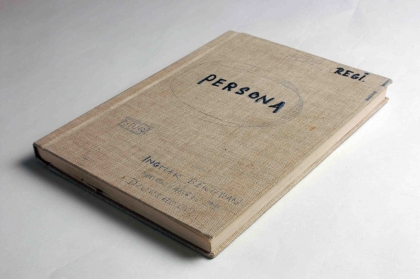

Considering the fact that a simple rubbish bin once owned by Bergman sold for over 2,500 euros at an auction, how much would the shooting script of Persona go for? Or original handwritten notes for The Seventh Seal?

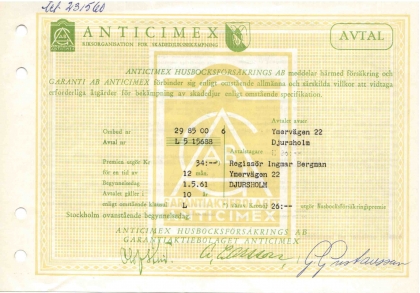

How about an invoice from Bergman importing Swedish sour milk to Germany during his Munich years, or his contract with Anticimex for longhorn beetle insurance? In the eyes of the archive, all items possess the same value.

As if the objects in the archive were well-aware of the historical circumstances which led to the founding principles of their organisation, a dull humming emanates from the archive boxes stored within the shelves late at night. Should you happen upon this room, listen carefully and you will hear the sound of an original manuscript whispering to a Post-it note, a laundry list mumbling to a Golden Lion, ‘Liberty, equality, brotherhood!’