The Ghost Sonata

'It seems that Bergman has finally done Strindberg complete justice and reached his own goal.'Henrik Sjögren

About the production

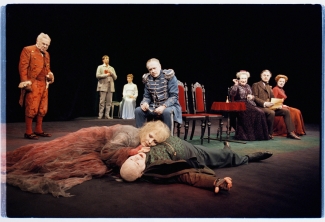

Bergman's fourth production of Strindberg's play. Bergman presented Old Man Hummel as the mastermind in a web of crimes and lies. His hands covered in bloody rags, perhaps a reference to the murder he once committed and possibly also to Strindberg himself, who suffered from psoriasis while writing the play.

There were other biographical allusions in the production: an image of the house at Karlavägen 10, were Strindberg once lived (at the time it was also Bergman's Stockholm address) was projected on the black cloth that framed the stage, and the sparse décor included a statue whose features were somewhat reminiscent of the actress Harriet Andersson.

The production was staged without intermission on The Royal Dramatic Theatre's small Målarsalen. In the programme Bergman referred to The Ghost Sonata as 'a piece of fantasy', a term Strindberg had used in a letter to theatre director Victor Categren in 1908. Musically, the play has usually been associated with Beethoven's 'Gespenstersonal' but Bergman used Bela Bartok as musical accompaniment, though his fourth reading of Strindberg's play had the dark mood of Beethoven's piece.

Almost all of the reviews were struck by the mercilessness and morbidity of Bergman's fourth The Ghost Sonata, referring to it as a depressing existentialist Strindberg compendium; a Judgment Day drama. 'It is a heavy, black and anxiety-ridden world that Ingmar Bergman depicts. A synopsis of a whole Swedish tradition but painted in a dark vision of sulphur and vitriolic'.

Swedish reviewers have tended to keep Bergman's theatre productions separate from his filmmaking. But a review of The Ghost Sonata said, '[The performance] begins altogether magically; as in a slowly rewound film, the actors step out from the wings. All enter with their backs to the audience, as if they had just exited and the director in the editing room had said "Stop! Rewind!"' Foreign critics who attended the Stockholm opening talked about it as a historical murmur. 'It is like a link back to Strindberg himself'.

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Birgitta Steene, Ingmar Bergman: A Reference Guide, (Amsterdam University Press, 2005).

- Ben Brantley, New York Times, 22 June 2001.

- Birgitta Steene, Ingmar Bergman: A Reference Guide, (Amsterdam University Press, 2005).

Ben Brantley, New York Times, 22 June 2001:

Decay is an irresistible force in Ingmar Bergman's exquisite, hideous and altogether stunning production of August Strindberg's The Ghost Sonata, currently haunting the Brooklyn Academy of Music. You can almost smell the flesh rotting in this fantasia on mortal corruption and deceit from The Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden. Yet even as you flinch, you are unlikely to look away. How could you, when the images are so sensuous and stark at the same time, so lush and still so disciplined in their composition? Seldom has cosmic disgust filled a stage so ravishingly.

[...] This is Mr Bergman's fourth interpretation of Strindberg's self-described chamber play, which occupies that intersection of dreams and reality that has long been this director's special province. At 82, he is dazzlingly confident in his command of the artifice and exaggerations required to render this singular work's grotesque comedy and steady undercurrent of pain. To put it more bluntly, he is a consummate showman who, dealing with uncomfortable and abstruse material, knows how to hook us and keep us hooked.

[...] The work's bleak vision may be baffling in its particulars, but it's not particularly subtle. The plot, if that word can be used, follows the perverse sentimental education of a student (Jonas Malmsjö), who is seduced into a web of relationships centered on the truly spiderlike old man in the wheelchair. This elderly character is played with a succubuslike passive vitality by Jan Malmsjö.

The play is divided into three scenes, or movements, that progress from exterior to interior, literally and otherwise. The first, set in the street, introduces the Student to the conniving Old Man and his world of lost souls, living and dead. [...] The second portrays the death-courting dinner party, the Ghost Supper, set to the fatal ticking of a clock and presided over by the Colonel (Per Myrberg) and his wife, known as the Mummy (the remarkable Gunnel Lindblom). The third finds the Student paying court to the daughter of the house (Elin Klinga), a rite compellingly staged here as a Bergmanesque wrestling match of the sexes.

Everyone has his or her nasty secret. And what seems glamorous from a distance is in close-up obscene. The elegant Dark Lady (Gerthi Kulle) lifts her veil to reveal an immense pustulant growth on her left cheek; her suitor, the Posh Man (Anders Beckman), dangles what looks like a loose vein from his mouth. (The essential wigs and masks are by Leif Qviström and Barbro Forsgardh.)

The Old Man's Fiancée of long ago (Margreth Weivers-Norström), a pathetically flirtatious specimen, has an oversize red ear. Then there is the Mummy, with her inflamed scalp and shrouds of lace, who moves and talks like a parrot. Standing in eternal reproach is a nude statue of the Mummy as a young woman. Like most other figures in the play, it will be stained with blood before the evening ends.

As a group, these ungodly creatures -- rounded out by two dusty servants (Örjan Ramberg and Ingvar Kjellson) -- bring to mind one of Goya's depictions of simian aristocrats, cancerous with vanity, or a tableau of upper-crust gargoyles out of Dickens. To tell the truth, as an assembly of tic-riddled, hollow poseurs and desiccated beauties, The Ghost Supper isn't so different from some Park Avenue dinner parties I've attended.

And the manipulative Old Man evokes any number of contemporary powermongers. It is Strindberg's contention, after all, that hell is nothing more than life on earth. And despite the period costumes (the stunning work of Anna Bergman) and the dialogue spoken in Swedish (there is, as usual, simultaneous translation through headsets), the self-devouring world conjured here can seem mighty close to that of Tom Wolfe's Bonfire of the Vanities, as read on a rainy day with a hangover.

All aspects of the physical production combine to create an environment that is both otherworldly and entirely too worldly. Göran Wassberg's set looks so spare and simple at first, yet as the evening continues, it seems to acquire by stealth richness and detail. The palette shifts from the urban blacks and grays of the street to the jewel tones of the interior of the Colonel's house. Pierre Leveau's wonderful lighting appears to translate surfaces into everything from grit to velvet.

Every detail counts heavily and often insinuates its way into your subconscious: the motif of light reflected on glittering objects; the botanical health of the hyacinths in a window box. There are moments when you may not trust your senses, as when the breathtakingly beautiful Ms Klinga first opens her eyes to reveal -- can it be? -- only blank white beneath the lids. She looks, in fact, like the marble statue of her character's mother. This Young Lady is deeply contaminated in ways the Student may not see at first, but that we certainly do. Ms Klinga [...] gives an astonishing physical performance, in which balletic grace suddenly degenerates into tics and spasms.

[...] Then there is Jonas Malmsjö's appealing Student, a sort of stand-in for the audience, who gradually exchanges his robustness for a more feverish energy. In the play's first 15 minutes or so, just after he has encountered the Old Man, he keeps saying he has to leave, and there are moments when you think -- and half hope -- that he might really escape.

Not a chance. Strindberg's house of horrors is, to borrow from Henry James, ''no evil dream of a night'. It is a reality from which no one awakes, at least in this world. Of course Strindberg isn't going to let the Student walk out. Through pure artistry, Mr Bergman exerts a similar hold on those watching these souls in captivity.

The Ghost Sonata was awarded the first annual Scandinavian Theatre Prize, a prize instituted to honour the best stage production of a Scandinavian play, put on by one of the three Scandinavian national stages.

Norway, Oslo Nationalteatret, Back Stage, 31 May-1 June 2001

Many reviewers had already written about the performance when it opened in Stockholm. One of the remaining wrote about the connection between the parasitical theme of Strindberg's play and the rationale behind the Attac movements struggle against global capitalism

Denmark, Copenhagen, Det Konglige, 9-10 June 2001

Three performances were held. Bergman was considered a director 'who unites, without much ado and with no self-adulation, his life-long experiences in the theatre and his self-evident genius. And the actors will follow him like angels in both farce and tragedy'.

USA, New York, Brooklyn Academy of Arts (BAM), 20-24 June 2001

Five performances were held and the critics were lyrical. 'Every few years Ingmar Bergman electrifies the Brooklyn Academy of Music with a bolt of his visionary theatre. And in the zap of an evening, we are stunned yet again with the power of a permanent acting ensemble, with the importance of marrow-deep understanding of style and master to transform theory and text into living, breathing, sweating stage genius'. Another critic compared the quality of Bergman's performance with the ordinary New York performances and was 'as ashamed of New York today as Hummel's victims are of their guilty secrets. The city's theatre, like the living-dead household where Arkenholz find himself, is poisoned at the very source of life'.

Collaborators

- Jan Malmsjö, The old man

- Jonas Malmsjö, The student

- Gertrud Mariano, The milkmaid

- Nils Eklund, The dead one

- Gerthi Kulle, The dark lady

- Per Myrberg, The colonel

- Gunnel Lindblom, The mummy

- Elin Klinga, The young lady

- Anders Beckman

- Örjan Ramberg

- Erland Josephson

- Margreth Weivers-Norström

- Gerd Hagman

- Margareta Hallin

- Peter Kleve, Props

- Per Cederin, Props

- Ulla Åberg, Dramaturgy

- Bengt Wanselius, Stills photographer

- August Strindberg, Author

- Tomas Wennerberg, Stage manager

- Virpi Pahkinen, Choreography

- Anna Bergman, Costume design

- Jan-Eric Piper, Sound

- Pierre Leveau, Lightning

- Béla Bartók, Music

- Leif Qviström, Make-up and wigs

- Barbro Forsgårdh, Make-up and wigs

- Sofi Lerström, Producer

- Ingmar Bergman, Director

- Ulph Bergman, Assistant director

- Anders Olausson, Props

- Claes Snell, Master carpenter

- Roland Åblad, Master carpenter

- Göran Wassberg, Designer

- Ulrika Behrenfeldt, Stage technician

- Hanna Pauli, Prompter