Winter Light

A country pastor whose congregation is in decline is beset with growing doubts.

"It is satisfying to see Winter Light after a quarter of a century. I believe nothing in it has eroded or broken down."Ingmar Bergman

About the film

In January 1961 Ingmar Bergman directs Anton Chekhov's The Seagull at the Royal Dramatic Theatre and August Strindberg's Playing with Fire for Swedish Radio Theatre. He is appointed artistic adviser to AB Svensk Filmindustri (a position previously held by Bergman's mentor and idol, Victor Sjöström). He wins his first Oscar, for The Virgin Spring, voted best foreign language film. On 22 April, the première is held of his now legendary production of Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress at the Royal Opera in Stockholm. At the same time he is putting the finishing touches to Through a Glass, Darkly, the first film, along with Winter Light and The Silence, of what would later be known as a trilogy.

His success is unprecedented. Bergman's status is such that he can – as he was to do the following year – turn down a 500,000 dollar contract with MGM, 24 times more than he was earning at the time. Yet he hardly feels comfortable with all this success, quite the opposite. 'I found myself in the position of being able to do what I wanted. It was time to risk a death-defying leap.' But this defiance of death is not simply an expression of courage. At the same time as he is cashing in on increasing success – not least internationally – Bergman still appears to feel misunderstood. Swedish critical opinion, although not lacking in admiration, is still basically unreceptive to a director who appears permanently obsessed with religious broodings at a time when the country in general is secularised, modern and hungry for success. Bergman confronts these constant reservations in an uncompromising way. He plans a film that not only features a doubting clergyman, but will also be 'ugly'. No cheap aesthetic tricks like 'a lot of uncalled-for direct light in a pretty girl's hair.' Furthermore, the stars of the film - Gunnar Björnstrand and Ingrid Thulin, two of Sweden's most stylish actors of all time – will be made to appear repugnant.

During the shooting of Winter Light, the crew give the film the apt nickname 'Snotty John and the Lip Balm'. They speculate on the sequel: 'The Further Tribulations of Snotty John and the Lip Balm'. Briefly speaking, Bergman is hardly expecting a hit. It is therefore no coincidence that during the course of the year he gives two interviews in which he predicts an imminent end to his success: the weekly magazine Se publishes an article in which Bergman compares his international celebrity to an influenza epidemic that 'goes from country to country, reaches its peak and then dies away'. An article in Expressen bears the telling heading 'Foreign interest in me just a fad soon to be over'.

There is a general tendency in Ingmar Bergman to complain of being misunderstood, yet also to boast about his outsider status. This is hardly the place for a psychological analysis of what lies behind this, yet it is obvious that with such an attitude, success is a double-edged sword. Seen in this light, it is logical that the film he is currently planning seems intended to give his adversaries new ammunition with which to attack him. And perhaps it is not so much an act of 'death defiance,' as one of psychological necessity.

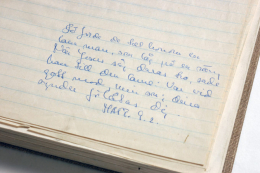

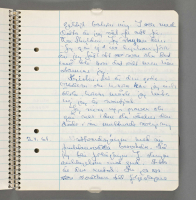

As so often in Bergman, the starting point for Winter Light was a piece of music. Whilst working on The Rake's Progress he listened to a great deal of Stravinsky, and when the 'Symphony of Psalms' was played on the radio one day over the Easter holiday, he decided he would like to make a film set in a solitary church on the plains of Uppland. In his workbook from the time, we can closely follow the film's genesis. This is the first note:

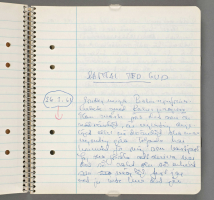

26.3.61

CONVERSATIONS WITH GOD

SUNDAY MORNING. Symphony of Psalms.

Work with Rake's progress.

One has to do what is necessary. When nothing is necessary, one should do nothing. The following has suddenly occurred to me. I shall try to write it down as starkly and simply as possible, yet I'm not sure how it will turn out.

In the next entry we find the first description of what was to become Winter Light:

This I know;

"I" go into an empty church to converse with God and to finally fall to my knees, to pray openly, to talk to God. To get answers, to give up my resistance at last or [unreadable] or this [unreadable] complication. The bond [unreadable] to the father, to the need for security or to that which does not exist which is like mice scurrying away in centuries gone by. Well now.

Next to this primitive altar in this deserted church, this drama about a human life is played out. Individuals materialise and fade away.

I go into the church, lock the door and remain there in a fever. Wait for the miracle which is akin to drinking from a woman's breast.

Blasphemy, contempt, hatred that knows no bounds. He encounters the altar of the church. The despairing silence of the night. The graves, the dead. [unreadable] and the rats. The smell of death and decay. The hour glass. The terror that the coming night will bring. The bottom has been reached. Gethsemane. The crucifixion. [Unreadable.]

I go out of my way, my own way from this thing, that is already obsolete and that I don't want to contemplate. With gratitude I leave my [unreadable], this grey nothing, shrunken, behind me with indifference. With this I am free to go. But Guilt. I strike it out. I will not leave the church before I have received an answer, be that as it may, but I am staying here.

Bergman's friend, the author and (later) film director Vilgot Sjöman was involved in the project at an early stage. He would subsequently become the film's assistant director, an experience he has documented in his excellent book L136: Diary with Ingmar Bergman. Yet at this early stage, he functions as someone whom Bergman bounces his ideas off: between Easter and Midsummer Bergman writes down various draft fragments which Sjöman reads and comments on. Quite quickly, the person of the initial notes becomes a pastor, and Sjöman is sceptical towards 'yet another film about a clergyman broken down by doubt in his faith' (even though he does not say so explicitly). On 14 June, however, Bergman develops his theme in a way that interests the non-believer Sjöman:

'You see, this person has a hatred of Christ that he won't admit to anyone. He is envious of Christ.'

'Envious?'

'Yes, and jealous. He feels something akin to the elder son's hatred of the prodigal son, who gets all the attention when at last he comes home: fatted calf and all the rest.'

It is also tempting to draw parallels between the clergyman in the film and Bergman's father, Erik. The pastor's name is Tomas Ericsson: Tomas (Doubting Thomas), Erik's son. Might there be an element of self portraiture in the character?

In early July Bergman and his wife go to the summer house they have rented on the island of Torö, where he quickly writes a preliminary screenplay. In the meantime, he lets Sjöman know how the work is progressing. On 20 July 1961 Sjöman receives a report from Bergman in which he confirms that he wants Gunnar Björnstrand and Ingrid Thulin to play the main parts. The pastor's wife, initially alive, is now dead:

I woke up one morning and killed her off. It was a lovely feeling. And right." He gives a loud laugh as he tells me about it.

[...]

Now the parson has a mistress instead. An hysterical, lonely, middle-aged, flat-chested school teacher in the country. So now things are moving.

Other vital elements also fall into place:

'I don't usually give a damn about world politics, but this spring I read in the papers about the Russians and the Chinese, and I discovered that it's not the Americans that the Russians are scared of, but the Chinese. The Chinese who are so regimented that you could easily imagine them starting a nuclear war. And reading all that made me very depressed.'

Bergman describes the ending of the film as the 'stirrings of a new faith'. He finds this a difficult section to write. Yet in a conversation with Sjöman he feels he has found a solution:

Have you ever heard of 'duplication'? On certain Sundays the parson has to hold two services: one in the main parish and then one in the chapelry, the sub-parish in the next district. Now it is custom in the Swedish church that if there are no more than three persons in the congregation, no service need be held. What I do is this: when Björnstrand comes to the district church, the church-warden comes up to him and says: 'There's only one churchgoer here.' Yet the parson holds the service all the same. That's all that is needed to indicate the new faith that is stirring inside the parson.

Later, in The Magic Lantern, Bergman recalls the ending as having come to him during a visit to a church in the company of his elderly father:

It was an early spring day with mist and bright light reflecting off the surrounding snow. We arrived in plenty of time at the little church north of Uppsala to find four churchgoers ahead of us waiting in the narrow pews. The churchwarden and the sexton were whispering on the porch while a female organist was rummaging in the organ loft. Even after the summoning bell had faded away over the plain, the pastor still had not appeared. A long silence ensued in heaven and on earth. Father shifted uneasily in his seat and muttered to himself and me. A few minutes later we heard the sound of a car speeding across the slippery ground outside; a door slammed, and after a minute the pastor cam puffing down the aisle.

When he got to the altar rail, he turned around and looked at his congregation with red-rimmed eyes. He was a thin, long-haired man, his trimmed beard scarcely covering his receding chin. He swung his arms like a skier and coughed, the hair on the crown of his head curly, and his forehead turning red. 'I am sick,' said the pastor. 'I have a high fever and a chill.' He sought sympathy in our eyes. 'I have permission to give you a short service; there will be no communion. I'll preach as best as I can, then we'll sing a hymn and that will have to do. 'I'll just go into the sacristy and put on my cassock.' He bowed and for a few moments stood irresolutely as if waiting for applause or at least some sign of approval, but when no one reacted, he disappeared through a heavy door.

Father rose from his seat in the pew. He was upset. 'I must speak to that man. Let me pass.' He got out of the pew and limped into the sacristy, leaning heavily on his stick. A short and agitated conversation followed.

A few minutes later, the churchwarden appeared. He smiled with embarrassment and explained that there would be a communion service after all, and an older colleague would assist the pastor.

The introductory hymn was sung by the organist and us few churchgoers. At the end of the second verse, Father came in, in white vestments, with his stick. When the hymn was over, he turned to us and spoke in his calm free voice, 'Holy, holy, holy Lord of Hosts, heaven and earth are full of thy glory. Glory be to thee, O Lord most High.'

Thus it was that I discovered the ending to Winter Light and a rule I was to follow from then on: irrespective of everything that happens to you in life, you hold your communion.

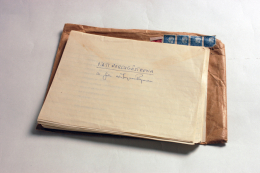

The screenplay is inscribed 'Torö, 7 August 1961, S.D.G.' S.D.G. stands for Soli Deo Gloria – 'Glory to God Alone'. Johann Sebastian Bach used to sign the bottom of each page of his compositions with the same initials.

Sources of inspiration

The immediate trigger for the film may well have been Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms, yet there were certainly other sources of inspiration. Given the film's religious theme, it has been the subject of an extensive exegesis, even by the standards of Bergman scholarship: theological interpreters have seen the film as a more or less disguised passion play. It has also been suggested that Tomas Ericsson passes through seven 'stations' which equate to Jesus' Way of the Cross. Others see Märta Lundberg as the film's Christ figure (like Jesus she is 33 years old, and has stigmata-like eczema on her hands and scalp). Bergman would later comment on this as follows:

Märta is something of the stuff saints are made of, i.e., hysterical, power-greedy, but also possessed of an inner vision. All tha business about the eczema on her hands and forehead, for example, I'd pinched that straight from my second wife. She used to suffer from it and went about with big pieces of sticking plaster on her forehead and bandaged hands. She had an allergic excema. But that it had anything whatever to do with stigmatization that's utterly wrong. For me Märta is something furious, alove, intractable, pig-headed, troublesome. A great and for a dying figure like the clergyman overwhelming person.

Yet even though Bergman has refuted certain religious interpretations, they are not without foundation: it is clear, at least, that he himself has viewed the film as a theological parable. This is especially apparent in L-136 where Bergman himself speaks of Tomas' various "stations" (something which in itself may just as likely refer to the Way of the Cross as to Strindberg's To Damascus). And Algot Frövik, the disabled church warden, is an angel. 'Really, literally: an angel. Ther is fifty times more religion in that man than in the whole character of the parson.' In various instances, Bergman interprets the film as a religious allegory: Tomas is the lame man of the New Testament, borne along by Märta and Algot. The relevant verse in the Bible was obviously of major relevance to the film: it is quoted as a motto in the hand-written screenplay:

'And, behold, they brought to him a man sick of the palsy, lying on a bed:

and Jesus seeing their faith said unto the sick of the palsy;

Son, be of good cheer; thy sins be forgiven thee.

Matthew, 9:2.'

Winter Light also has parallels with earlier, non-Bergman films. Its pared-down qualities are reminiscent of the work of Carl Theodor Dreyer or Robert Bresson. Bergman sees the latter's Diary of a Country Priest for the third time shortly before shooting began, in the company of Ulla Isaksson and Vilgot Sjöman. Dreyer's theories about 'abstraction' as a means to reach beyond the surface of things, thereby amplifying the spiritual, is also a method employed by Bergman in Winter Light. Whether or not he had read Dreyer's book About Film: Articles and Interviews, which had been published two years previously, it is clear that he adopted the method in his acknowledged admiration for Dreyer.

Shooting the film

Almost all of Bergman's films are shot during the summer, for a number of reasons. Partly, he was engaged in theatre work during the rest of the year; and partly, as he himself has said, he made films to provide his actors with work when the theatres were closed. Furthermore, summer is a theme in itself in his films: Summer Interlude, Summer with Monika, Smiles of a Summer Night, etc.

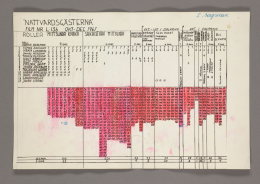

Nattvardsgästerna, (literally: The Communicants), on the other hand, given the English title 'Winter Light' for US distribution, was to take place in the winter. As Bergman much later would summarise the film: 'A Swedish man in the midst of Swedish reality experiencing a dismal aspect of the Swedish climate.'

Shooting began on 4 October 1961. 'The shooting was extremely demanding, and dragged on for fifty-six days. It was one of the longest schedules I've ever had, and one of the shortest films I've ever made.' For various reasons, shooting was beset with difficulty. The fact that only a handful of people believed in the film must have played its part: the people at SF were sceptical; the actors found it hard to get to grips with their roles; and even Bergman's wife, Käbi Laretei, declared after reading the screenplay, 'Yes, it's a masterpiece, Ingmar. But a dreary masterpiece.'

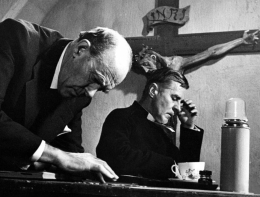

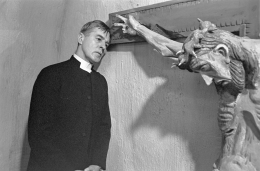

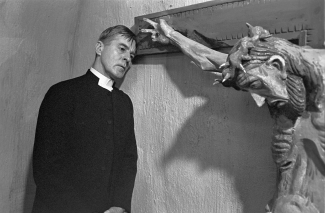

Yet the main source of concern was Gunnar Björnstrand. No other actor has taken part in so many Bergman films as Björnstrand did; no other was such a sympathetic interpreter, often of characters that bore many similarities to Bergman himself. To Swedish audiences at the time Björnstrand was best known as a comedy actor, and his collaboration with Bergman began with the comedies made in the early 1950s. Now he was set to play one of the most dour characters in cinema history.

The stylish, quick-witted comedian was to be reduced to a wreck. The fact that his character was a clergyman beset with doubt as to the existence of God cannot have helped matters for Björnstrand, a recent convert to Catholicism. But he was a thorough professional – so all of this should have been possible. Yet the problems ran deeper. In Images: My Life in Films, Bergman provides a laconic clarification of the situation: 'Gunnar found it painful to portray a person who was unsympathetic to such a degree. His inner turmoil became so acute that he had trouble remembering his lines, a problem that had never happened before. Furthermore, he had health problems, and for his sake we worked relatively short day shifts.'

These "health problems" were rather more than a common cold. On 27 September, a few days before shooting is due to start, Björnstrand goes for a medical check-up. There are many twists and turns to this story, yet according to his wife, the writer Lillie Björnstrand, the check-up was at Bergman's insistence, under the premise that the role was so demanding. Björnstrand protested that he was in robust health, but the SF company doctor prevailed and carried out the examination. The diagnosis was high blood pressure and he was placed under strict doctor's orders: no alcohol, no sex, etc. Otherwise, he warned, the actor would be at risk of cerebral haemorrhage and paralysis. On the other hand, the doctor saw no reason why he should pull out of the shooting, despite Lillie's entreaties.

'Gunnar was frightened to death. He couldn't sleep, couldn't banish the thoughts of death and paralysis from his mind. It was sheer hell. We stayed awake during the nights that remained before he was due up at the film shoot in Dalarna.' When he arrives at the studio the next day, the atmosphere is strained. In his book of interviews Vilgot Sjöman recounts a question he asked Bergman that day: 'You look so goddam smug when you speak of Gunnar's illness.' Bergman laughed and said: 'Well, of course it is wonderful that Gunnar is so off-color and unwell when heäs to play this sort of part. Imagine if I'd gotten a sun-tanned, hale-and-hearty guy to play someone worn out and ailing!'

It is disagreeable to think that the director to some extent welcomed the illness for the sake of the film, yet the situation was to take a further turn for the worse. Björnstrand is so upset by the news that he decides to get a second opinion, and is examined by the heart specialist Clarence Craaford. The results were the exact opposite: his blood pressure was considerably lower, there were no risks either for a heart attack or a cerebral haemorrhage. Craaford also discarded half of the medicines previously prescribed for Björnstrand and after a week he stopped taking any medicine and felt fit once again. It is impossible to apportion any blame, but is clear that Björnstrand himself believed that his director had manipulated him in some way into believing that he was ill. Although Björnstrand did not say so in so many words, the perceptive Sjöman discerned something in the relationship between the two:

There is a tension between Ingmar and Gunnar. It has evidently increased the last few days. What it consists of I dont really know yet. With Gunnar I notice a feeling of not being free; an idea that Ingmar has a deep contempt for actors, 'And when you've done a good job, you still don't get the credit for it yourself.' With Ingmar I notice an aggressiveness which he cannot camouflage: his tone is sharp, and Gunnar tightens up still more. Gunnar is silent or aggressive in return. Ingmar seems disappointed. Gunnar too. How is that tension going to affect the film?

Even after he is declared fit, Björnstrand is still shattered. The role is a difficult one, made all the more difficult by the suspicion that his friend Ingmar has deceived him. Bergman continues to appear unaffected. At one point the make-up artist Börje Lundh is worried that Björnstrand's appearance has changed; that he has become noticeably thinner. They ask Bergman what they should do, since the first half of the film is already in the can: 'It doesn't matter if he's a bit hollow-cheeked. Good thing, in fact. Lose a bit more weight!'

Accusations in respect of Bergman's role in this unpleasant story – which as far as we are aware is only down to a wrong diagnosis and a desire to smooth things over – have not ceased to flow. To coincide with the TV premiere of Saraband 2003, Björnstrand's daughter Gabrielle wrote an article for the newspaper Expressen under the heading 'Gabrielle Björnstrand on her father: Bergman psyched out his favourite actor'. She observes that 'no employer has a right to abuse people and there are no special rules for so-called geniuses.' In this context it is apt to draw attention to Bergman's recurrent notion of the artist as cannibal, whose art profits from the sufferings of others: consider David in Through a Glass Darkly, Elisabet Vogler in Persona or Elis Vergérus in A Passion. Björnstrand's performance, especially under the circumstances, is brilliant. One of Sweden's all time great actors in what is perhaps his finest ever role. In Sjöman's words: 'I see Gunnar's performace in Winter Light growing into a great performance – but it is frowing out of a press of anguish.'

The other star of the film was Ingrid Thulin, recently returned to Sweden following a spell in Hollywood, where she had been shooting The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, directed by Vincente Minnelli. Both she and Bergman were to joke that she had become 'Hollywoodified', yet the role of Märta Lundberg was far from glamorous. And ever though her part was somewhat less demanding than Björnstrand's, her performance was no less brilliant. The long scene in which she in one single take reads a letter straight into the camera, without the help of an autocue or any other props, is an acting master class. The fact that she does not blink once during the entire eight minutes of the scene is just one of the many feats of her performance. Make-up artist Gullan Westfeldt has also noted that only on one occasion during all the takes when Märta Lundberg cries, did she need to use glycerine; her tears were entirely her own.

Thulin was also subject to external pressures. Her husband Harry Schein hated the film – one of his complaints was that the lines about the Chinese were so ridiculous that they could have been lifted from Sweden's absurdly satirical magazine Grönköpings Veckoblad. 'I thought it was so bad that I tried to get Ingrid to turn down Winter Light. I intrigued as hell, but I was caught in my own trap.' In between takes Thulin often withdrew, either to her hotel room, or she would lie and rest on one of the church pews, out of sight of everybody. Bergman: 'Ingrid is like the beaver at Skansen [Stockholm outdoor museum and zoo]. Everyone stares at it but can never catch more than a glimpse. It doesn't even appear at feeding time.'

Sven Nykvist and Bergman had worked together on three films, Sawdust and Tinsel, The Virgin Spring and the preceding production Through a Glass Darkly. The latter had proved difficult, not least in terms of lighting. Much of the film took place at dawn or dusk, often giving them just ten minutes in which to shoot a scene before it got too light or too dark. So Nykvist was relieved when he read the screenplay for Winter Light:

– This'll be easy, I said to Ingmar. "Three hours in a church in the middle of the day. The light doesn't change much then.Ingmar almost flared up:

– You don't know much, do you? That's precisely what it does, and that's precisely what I'm looking for. That gradual, almost indiscernible shift, virtually without a shadow.

The leaden-grey, contrast-free tones of Through a Glass Darkly were to be maintained and the demand for realistic light intensified. In common with everyone else, Nykvist recalls that the shooting was very demanding:

In itself it was no light-hearted film and I have no wish to hide the fact that I went into the project under strong protest. Afterwards, I remember shooting as having been difficult – with lots of irritation between Ingmar and myself. Yet at the same time, we gelled together in a strange kind of way, and for me as a cinematographer that film was probably the major turning point, the one in which I learnt the major significance of reduction, of cutting out all artificial lighting, all illogical lighting. Ingmar quite literally forced me to be one hundred per cent realistic in my lighting.

There is, however, one scene in which Bergman abandons his principles on what he refers to as 'logical' light, and this occurs in one of the last scenes, during Algot Frövik's discussion with Tomas about the suffering of Christ. 'Make a beautiful light, Sven', he had said, 'Frövik is an angel.' Nykvist also recalls that virtually all of the film was shot in cloudy weather.

'Only in one scene, with Gunnar Björnstrand kneeling at the altar rail, was the sun to break through the clouds, God's mercy! It was the most difficult scene of all. In one pan we were supposed to follow the ray of sunshine that breaks through from the darkness of the church entrance, gliding slowly over the windows and finally coming to rest at the altar.' And, as he sums up: 'In terms of light, Winter Light is one of Ingmar's most striking films, yet something that few people think about when they are watching it. Plainness is more thankless than picturesque lighting. Nobody appreciates the work that lies behind it.'

Epilogue

Winter Light is the first of Bergman's films for which editing begins while the film is still being shot. A room in the hotel in Rättvik where the crew is staying serves as a makeshift cutting room. On 22 November 1961, Bergman, Nykvist and the editor Ulla Ryghe run through all the takes of the church interiors that have been shot in the church at nearby Skattungbyn. Scrutinising these takes, Bergman and Nykvist decide that the images are too beautiful: 'All that brilliance! All that charming light, don't you think it's wrong, Sven?'

They resolve that the scenes have to be shot again, and they decide to reconstruct Skattungbyn church in the Råsunda Film Studios. Later, Ulla Ryghe tells Vilgot Sjöman that during the conversations between the cinematographer and his director she sat in silence, hoping they would re-shoot the scenes, otherwise for the rest of the filming they would have plagued themselves and everyone around them over the takes that were not quite right.

Shooting comes to an end on 14 January 1962. The actors are probably relieved that the ordeal is over, but for Bergman, Nykvist and Ryghe the work continues relentlessly. For the mixer Olle Jacobsson and sound engineer Evald Sandersson it has only just begun. During the editing Bergman contemplates cutting down the introductory communion scene. It is one of the most uncompromising scenes in his entire filmography; the original idea being that this consciously deathly-dull scene would take up half the film.

Sjöman is opposed to the idea on the grounds that they have put so much work into the scene. Bergman's response: 'Do you think that is an obstacle? Never. If it's wrong, it's wrong; and it must come out. However hard you have worked on it.' Ulla Ryghe is also sceptical of editing down the scene: a certain inexorability would be lost, she feels. Bergman, however, believes that there might be an audience-related reason to shorten the scene. 'People can get so exhausted by it that they are not receptive to the rest of the film. If they are bored at the beginning, they won't listen to the rest.' Even in this, his most uncompromising film to date, he cannot disregard public demand – the 'audience whore' – as he has mockingly referred to himself, is still present within him.

The letter scene had been a baptism of fire during the shooting, not only for Thulin, but also for the sound engineer who had had great difficulty in placing the microphone so that all the nuances of sound were picked up, but not the whirr of the camera. With a certain degree of bitterness Bergman remarks when they are mixing the sound that nobody will understand what a technical challenge the scene was: 'They think all you have to do is stick a camera straight in front and that's it.' He also regrets what an international audience will miss in the scene: 'The entire letter will be ruined in the international market, because the spectator's eyes will move up and down between the subtitle and Ingrid's eyes. Pity. It will spoil the whole fascination with her eyes. This is indeed a specifically Swedish film.'

There is no place for sentimentality when editing the sound. The scene where Märta comforts Tomas at the altar had been extremely moving during the shooting (as it is in the finished film), but right now Bergman is fairly brusque, as he orders the mixer and sound technician to "Keep the dialogue down, boys, so we get all these nasty, messy kisses it must be so that we want to spew on the woman

"

Later on in the mixing process, a dog is supposed to bark in the Persson's yard ('and none of your dachsuhunds, it must be a Lapland spitz'). New barks are attempted by the unfortunate sound engineer Evald Andersson: 'That's a dog from the sound effects department. We can't have that! [...

] Another recorded dog. Now look here, boys, you'll damn well have to get a real dog. We can't go on like this.'

When the work is finally finished and the premiere is approaching, Bergman observes once again, as he did while writing the screenplay, that this will hardly be a blockbuster. Kenne Fant and the director estimate that the film will make 400,000 kronor in Sweden, the lowest sum for very many years in Bergman's film career. Yet they also count on receiving a quality subsidy of 200,000 kronor. International rights to the film have already been sold for half a million kronor ("poor bastards, they don't know what they've bought!"). So in financial terms, the film should pay for itself. But only just.

The film has its public premiere in Stockholm on 11 February 1963 (the evening before there had been a special preview in Falun for the benefit of the church in Skattungbyn, where shooting originally took place). Press reactions can be summed up in the telegram that Kenne Fant sent to Bergman, on holiday in Switzerland: 'Two for. Two against. An in-betweeny.' Robin Hood, writing in Stockholmstidningen was decidedly against: 'What, to me as an individual, are Bergman's religious introspections hither and thither? A person's dealings with God should be kept private and behind closed doors, not charged for via an admission ticket weighed down with entertainment tax.'

Lill in Svenska Dagbladet was for, but notes that she could well be alone:

Ingmar Bergman puts his audience to the ultimate test. If they take on board this doomsday sermon without grumbling and with an open mind, he will have definitively won them over and likewise won a victory over all conventional opinion regarding the cinema. Personally I was, as always, a helpless victim of Bergmanesque suggestion, of the energy that certainly does not lie in surface events and devices, of the seriousness and urgency whereby he conveys his Jacob-like struggle and demands participation. I can imagine that many people will be bored and unreceptive, that they will oppose, criticise, make fun of and deride the film.

She was right. The film was seen by a considerably smaller audience than Bergman was accustomed to (even if his subsequent film The Silence would have them flocking back again in ever greater numbers, but probably for dubious reasons: the film attracted the label 'pornographic'). Bergman's predictions, when on the second day of shooting he observed: 'This morning I got stuck in a goddam great traffic jam. I sat there looking at the drivers in the other cars. And thought: You won't come and see Winter Light, and you won't come and see Winter Light, and you won't come and see.' were to come true.

Winter Light sparked off a theological debate, not least because a number of daily newspapers sent questionnaires to clergymen asking their opinion of the film. As Vilgot Sjöman points out, the film, through no fault of its own, was used as a weapon in the debate raging at the time between the high and low church, the former of which saw the film, to quote Bishop Bo Giertz, as: 'a mighty and upsetting document about the Swedish church in its deepest abasement'. As expected the film was quite badly received abroad . It would have been convenient to blame this on the notion expressed by Bergman that the film was so typically 'Swedish' as to make it incomprehensible for an international audience, were it not for the fact that the Swedes did not understand it either. 'Boring" was the general opinion, both at home and abroad. Newsweek carried a telling heading for its review: 'Wake Up, Ingmar'.

Winter Light picked up a couple of awards at minor festivals, yet the contemporary view was that this was an 'in between' film. It would take time before it came to be regarded as a masterpiece (if indeed it ever truly has).

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern.

- Stig Björkman, Torsten Manns and Jonas Sima, Bergman on Bergman (New York: Da Capo P., 1993).

- Gabrielle Björnstrand, "Gabrielle Björnstrand om sin far: Bergman psykade sin favoritskådespelare", Expressen, 12 January 1963.

- Lillie Björnstrand, Inte bara applåder, (Stockholm: Tiden, 1975).

- Sven Nykvist, Vördnad för ljuset: om film och människor, red. Bengt Forslund, (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1997).

- Vilgot Sjöman, L 136: Diary with Ingmar Bergman (Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers, 1978).

Distribution titles

Les communiants (France)

Los comulgantes (Spain)

Goscie wieczerzy panskiej (Poland)

Hasté vecere páne (Czech Republic)

Licht im Winter (West Germany)

Luci d'inverno (Italy)

Luz de inverno (Portugal)

Luz de invierno (Uruguay)

Lys i mørket (Denmark)

Nattverdsgjestene (Norway)

Pricastie (Soviet Union)

Pritjastie (Soviet Union)

Talven valoa (Finland)

Winter Light (Great Britain)

Winter Light (USA)

Production details

Production country: Sweden

Swedish distributor (35 mm): Svensk Filmindustri, Svenska Filminstitutet

Laboratory: FilmTeknik AB

Production company: Svensk Filmindustri

Aspect ratio: 1,37:1

Colour system: Black and white

Sound system: AGA-Baltic

Original length (minutes): 81

Censorship: 099.920

Date: 1962-11-19

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2215 metres

Release date: 1963-02-11 Cosmorama, Göteborg, Sweden, 81 minuter

Kaparen, Göteborg, Sweden

Fontänen, Stockholm, Sweden

Röda Kvarn, Stockholm, Sweden

Skandia, Uppsala, Sweden

Filming locations

Sweden (1961-10-04-1961-11-01) (studio)

(1961-11-08-1961-12-01) (exteriors)

(1961-12-05-1961-12-13) (studio)

(1962-01-08-1962-01-17) (studio)

Filmstaden, Råsunda, Stockholm, (studio)

Skattunge kyrka, Orsa kommun

Ungsjöbodammen (near by Skattungbyn), Orsa kommun

Skattungbyn, Orsa kommun

Finnbacka, Rättviks kommun

Norrboda, Rättviks kommun

Rättvik, Rättviks kommun

Music

Title: O Guds Lamm, som borttager världens synder Alternative title: Agnus Dei

Singer: Erik Sædén

Title: Herren vare tack och lov!

Singer: Erik Sædén

Title: Sist, min Gud, jag dig nu beder

Lyrics: Gustaf Ållon (1694)

Arrangement: Jan Arvid Hellström (1979)

Singer: Erik Sædén

Title: Lova Herren Gud, min själ

Lyrics: Jakob Arrhenius (1694)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Postludium (Morén)

Composer: John Morén

Comment: Instrumental.

On a cold winter's Sunday, the pastor of a small rural church (Tomas Ericsson) performs service for a tiny congregation; though he is suffering from a cold and a severe crisis of faith. After the service, he attempts to console a fisherman (Jonas Persson) who is tormented by anxiety, but Tomas can only speak about his own troubled relationship with God. A school teacher (Maerta Lundberg) offers Tomas her love as consolation for his loss of faith. But Tomas resists her love as desperately as she offers it to him. This is the second in Bergman's trilogy of films dealing with man's relationship with God.

Collaborators

- Ingrid Thulin, Märta Lundberg, teacher

- Gunnar Björnstrand, Tomas Ericsson, priest

- Gunnel Lindblom, Karin Persson

- Max von Sydow, Jonas Persson, fisherman, Karin's husband

- Allan Edwall, Algot Frövik, sexton

- Kolbjörn Knudsen, Knut Aronsson, churchwarden

- Olof Thunberg, Fredrik Blom, organist

- Elsa Ebbesen-Thornblad, Magdalena Ledfors, widow

- Tor Borong, Johan Åkerblom, freeholder

- Bertha Sånnell

- Helena Palmgren, Doris, Hanna's daughter

- Eddie Axberg, Johan Strand, boy in classroom

- Lars-Owe Carlberg

- Ingmari Hjort, Persson's daughter

- Stefan Larsson, One of Persson's sons

- Johan Olafs, The superintendent's assistant

- Lars-Olof Andersson, Fredriksson's boy

- Christer Öhman, Fredriksson's boy

- Karl-Arne Bergman, in för Allan Edwall

- Sirkka Jehkinen, Stand-in (for Gunnel Lindblom)

- P.A. Lundgren, Art Director

- Brian Wikström, Boom Operator

- Sten Lindén, Driver

- Gerhard Carlsson, Gaffer

- Sven Nykvist, Director of Photography

- Rolf Holmqvist, Assistant Cameraman

- Peter Wester, Assistant Cameraman

- Ulla Ryghe, Film Editor

- Max Goldstein, Costume Designer

- Evald Andersson, Supervising Sound Editor

- Stig Flodin, Production Mixer

- Börje Lundh, Make-up / Hair

- Olle Jakobsson, Re-recording Mixer

- Yngve Söderlund, Key Grip

- Rune Håkansson, Key Grip

- Allan Ekelund, Production Manager / Production Coordinator

- Lenn Hjortzberg , Assistant Director

- Vilgot Sjöman, Assistant Director

- Katinka Faragó, Script Supervisor

- Gullan Westfelt, Make-up Supervisor

- Ingmar Bergman, Screenplay

- P A Lundgren