Family Values

The family plays a central part in most Bergman films, but happy families are rare.

"Personally I was an unwelcomed child in a marriage which was a nice imitation of hell."Evald in Wild Strawberries (1957).

Family Values

Marriage in Bergman is almost always a Strindbergesque 'dance of death', and relationships between parents, children and siblings are, to put it mildly, strained. If happy relationships do occasionally exist, they usually involve a young couple in love before that love is institutionalised by marriage or having children. Once a relationship is established in a Bergman film, a crisis is frequently in the offing.

The family is one of three recurrent motifs used by Bergman as examples of, or metaphors for, his principal theme: lack of communication. The other two are religion (in which the silence of God is a metaphor for the paucity of contact between people) and art (in which the artist is a parasite who profits from other people's charity and unhappiness). The family becomes a distillation of society and its rituals of degradation. What these three themes – religion, art and the family have in common is that they are institutions that formalise the human need for contact. They are the given pillars of society which, as Bergman often depicts with painful clarity, exercise various forms of violence, thus negating true companionship and community.

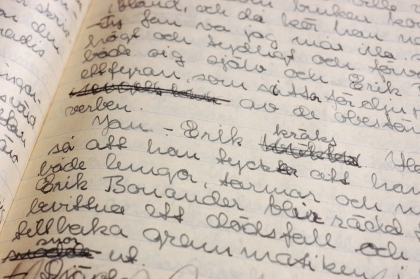

One of Bergman's first scripts, ironically entitled 'Family idyll' (1939).

© Ingmar Bergman Foundation.

It is clearly a subject close to Bergman's heart. He has often returned to his own childhood, with his strict and feared father and his beloved mother. Various forms of physical and psychological punishment were commonplace. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the earliest of his prose works to have survived written at the age of twenty and never published bears the ironic title 'Family Idyll' and is a young person's coming-to-terms with the falsity of his own childhood. (The piece formed much of the basis for his first screenplay, Torment) With a symmetry he probably never planned, his very last film Saraband is also about a rebellion against parents: Henrik rebels against his own father, and his daughter rebels against him.

In the sixty five years between these two works Bergman was to return in film after film to variants on the family theme. In broad terms this theme can be divided into four categories: the young couple (with bleak prospects); marriage; sibling conflicts and the humiliation of the child.

The Young Couple

It is in Bergman's earliest films It Rains on Our Love, Music in Darkness, Waiting Women, Summer with Monika that we most often encounter the young couple. Bergman himself was young, yet quite without illusions, it would appear (by the time he made his first film he had already been through his first divorce). The young couple, whilst happy and in love for a while, rarely have any prospects of a bright future together.

Harriet Andersson and Lars Ekborg in Summer with Monika (1953).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

What these depictions of young couples share in common is that their happiness appears to be in inverse proportion to the involvement of society around them in their relationship. As long as they are alone with their love, everything is well. It should, however, be pointed out that these films are fairly untypical of Bergman, and in many ways his early works were something of a training ground. It is when he 'matures' as a filmmaker above all when he writes his own screenplays that we discern his most manifest and important family themes.

Marriage

Depictions of marriage constitute the largest category in Bergman's family dramas: indeed, marriage is one of the themes on which his reputation is based. In the first film he both wrote and directed, Prison, we encounter a principal character whose marriage virtually drives him to murder and suicide. Bergman's early portraits of marriage sometimes reveal glimmers of hope, but the relationships either end badly, or else love itself is poisoned by what the director often claims to suffer from himself: "retrospective jealousy". In Thirst, for example, we find Rut and Bertil, whose marriage is a living hell. They finally realise that they do indeed belong together, but only after Bertil has had a nightmare in which he has murdered Rut. In To Joy the violinist Stig blames his professional failures on his wife Marta, and leaves her. When he finally decides to come back, she dies in a car accident.

The comedies of the 1950s Waiting Women, A Lesson in Love and Smiles of a Summer Night all end happily in some way or other, as one might expect. Yet even these works do not hold out much hope for marriage. Jealousy and infidelity poison relationships, and the films, in Bergman's own words, " play with the horrifying realisation that couples love one another despite not being able to live together."

Karin and David in an atypically tender moment in The Touch (1971).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

During the 1960s and 70s Bergman's depictions of marriage became increasingly desolate. Hour of the Wolf the married couple are expecting a baby when the husband attempts to shoot his wife and subsequently flees. Jan and Eva's marriage in Shame is tested to the limits during the war, and in The Touch, Karin is married to Andreas, yet drawn to her lover, David, who beats and abuses her. However, Bergman's most thorough analysis of marriage is clearly to be found in Scenes from a Marriage. Johan and Marianne appear to be happy together until Johan reveals that he is having an affair. They quarrel, fight and divorce, and are only reconciled once both of them have remarried.

One of the opening scenes, in which the main characters have invited their friends round for dinner, is among the funniest and most disturbing that Bergman has ever filmed. The mutual humiliation rituals performed by Peter and Katarina make Strindberg's marriage depictions in Married ('Giftas'; the Swedish word 'gift' literally means both 'married' and 'poison') or A Madman's Defence ('En dåres försvarstal') appear harmonious. Bergman's own words aptly sum up the scene, and also his own view of most marriages:

Peter and Katarina cannot live with each other or apart. They commit cruel acts of sabotage against each other, actions that only two individuals this close could invent. Their time together is a sophisticated and destructive dance of death. (Images)

A de-humanising process: it would appear that Bergman's pessimistic view of marriage could be summed up with these words. When love is formalised and sanctioned by the rituals of society, the predicament that affects so many of Bergman's characters arises: they cannot live with or without each other. This applies not only to marriage. The human condition, Bergman seems to imply, is characterised by a need for closeness with others, but all attempts to get close, to express that need, fail, and in the process one harms both oneself and others.

Sibling conflicts

Although not so common in Bergman's films, sibling conflicts certainly deserve a mention. The eponymous Fanny and Alexander appear to be the only siblings in his work whose relationship is relatively problem-free: their mother and father's relationship is plagued by jealousy and their stepfather's relationship with his own sister appears unhealthy. The two sisters in The Silence torment each other in a similar way to Peter and Katarina in Scenes from a Marriage: with "cruel sabotage" that always finds the weak spots.

Anna with her son Johan and her sister Ester in The Silence (1963).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

Cries and Whispers is perhaps the most bitter of all Bergman's depictions of siblings: when Agnes is dying her sisters react with disgust and abhorrence. Her anguish on the point of death is intensified by her sisters' lack of love. Her only solace comes from the servant, Anna, not a member of the family: indeed a person whose services are bought.

The Humiliation of the Child

One only has to look at his later works, especially the autobiographical ones like Fanny and Alexander, The Best Intentions and Sunday's Children, to see how Bergman's frequent punishments as a child have left an indelible impression that he has grappled with in his later professional life.

Yet, as mentioned elsewhere, the humiliation of the child is present even in his earliest writings. However, in early Bergman the children in question have usually grown up and started to revolt against their parents.

During the 1960s – heralded by the almost cameo depiction of Evald in Wild Strawberries – the vulnerability of children reappeared with greater intensity. In The Silence, the boy Johan appears to be completely left to his own devices while his mother occupies her time with erotic escapades. And never having wanted any children, Elisabet in Persona consequently neglects her son.

It is in Autumn Sonata, however, that the child/parent theme finds a new emotional intensity in Bergman, and once again the children have grown up: Charlotte is a self-obsessed, dominant mother with little interest in her two daughters. The films centres on Eva's confrontation with her mother, who refuses to appreciate what she has subjected her children to.

Otherwise Fanny and Alexander is probably the most well known of Bergman's depictions of the vulnerable child. On a number of occasions Alexander is caught lying by his stepfather, and the ritual of punishment and apology becomes increasingly refined.

Alexander's stepfather, Bishop Edward Vergérus, disciplines the eponmymous hero of Fanny and Alexander (1982).

Photo: Arne Carlsson. © AB Svensk Filmindustri.

Those who have read The Magic Lantern will recognise these rituals from the director's own childhood experiences. Yet Bergman's own memories may well have been fuelled by August Strindberg, who, in a famous passage from Son of a Servant Woman writes:

Splendid, moral institution, holy family, irreproachable and divine foundation for bringing up citizens in the ways of truth and virtue! Reputed seat of virtue, where innocent children are tortured into their first lie, where willpower is crushed to pieces by despotism, where self-esteem is suffocated by selfishness. Family, the home of all social evil, a charitable establishment for all comfortable women, an anchorage for bread-winners, and a hell for children!

Strindberg's rant against the family quoted, incidentally, in a scene from Bernardo Bertolucci's Last Tango in Paris (1973) is one with which Bergman appears to identify. It serves rather well to sum up his own views on the institution.

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives

- Images, Ingmar Bergman

- The Magic Lantern, Ingmar Bergman