Film history according to Bergman

Having an interest in film is perhaps not so unusual for a filmmaker. In Bergman's case, however, 'interest' is a definite understatement.

'Not until 1949, when I travelled abroad for the first time and spent two months in Paris, where I raced to the Cinémathèque Française on Rue de Messine, did I begin to seriously study film.'Ingmar Bergman

Bergman's cinema

A high point in Ingmar Bergman's life took place on 14 July 1975. On this day, his 57th birthday, he indulged in his very own cinema. Since his childhood days of hurrying to Slotts Cinema in Uppsala and Fågel Blå Cinema in Stockholm, his fascination with moving imagery resembled more of a passion than just a mere interest.

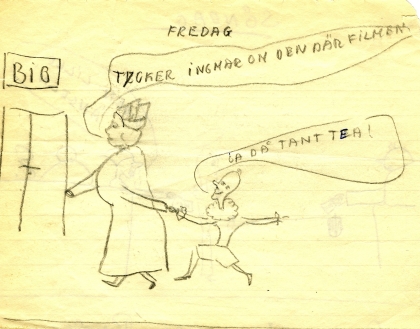

Teckning av Ingmar Bergman, c:a 1934.

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

When describing, in The Magic Lantern, how he built his first cinema in his nursery wardrobe, he becomes so excited that he loses the plot:

Then I turned the handle! It is impossible to describe this. I can't find words to express my excitement. But at any time I can recall the smell of the hot metal, the scent of mothballs and dust in the wardrobe, the feel of the crank against my hand. I can see the trembling rectangle on the wall.

I turned the handle and the girl woke up, sat up, slowly got up, stretched her arms out, swung round and disappeared to the right. If I went on turning, she would again lie there, then make exactly the same movements all over again.

She was moving.

When he did eventually build his own actual cinema as a distinguished, successful, middle-aged film director, it came as no surprise that he called it 'The Cinematograph'.

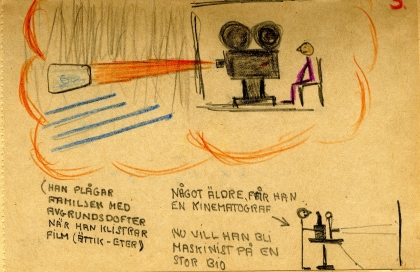

Bergmans självbiografi (i flera hänseenden) anno 1939.

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

This was not your average home cinema. In an old wooden barn in the village of Dämba in Fårö, he had a fully-functioning cinema built, equipped with two 35-mm and one 16-mm projectors.

From May to October, he watched at least one film a day, six days a week. His daughter Lena calculated that he must have logged 8,000 hours in The Cinematograph.

Bergman's housekeeper handled the logistics and worked as the projectionist. Borrowing films from various Swedish film distributors and the Swedish Film Institute, Bergman enjoyed afternoons on his own or in the company of others. Moreover, he possessed possibly Sweden's largest private cinematheque in terms of film prints in various formats.

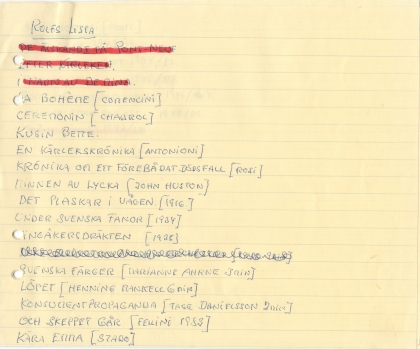

Rolfs lista 1991. Rolf Lindfors var chef för Svenska Filminstitutets filmarkiv; detta är första sida av fem av det årets önskelista.

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

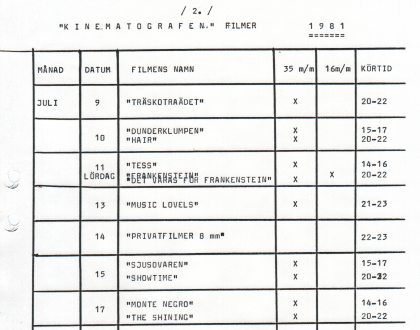

The Cinematograph's repertoire was varied, to say the least. Bergman watched everything. In July of 1981, according to his viewing journal, he watched such contemporary films as Tess, Young Frankenstein, Dressed to Kill, Stalker and The Shining, while also taking in such classics as the original Frankenstein and Love and Journalism. He also often watched his own films.

Ur visningsjournal juli 1981.

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

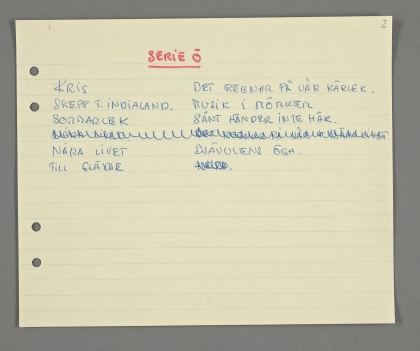

When Bergman voiced his opinions on his colleagues' work – both present and past – he was more knowledgable than most. His taste, however, can certainly be disputed. A number of his lists and other thoughts are included on the left of this page, to either agree or disagree with, quite often to marvel at. Did he like it? How could he not like it? And so forth.

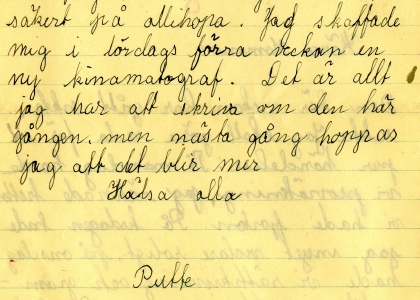

I ett brev till föräldrarna från sin sommarvistelse hos mormodern i Uppsala berättar den tolvårige Bergman att han har köpt en ny kinematograf.

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

Sources

- Ingmar Bergmans Arkiv

- Jan Aghed, "När Bergman går på bio", Sydsvenska Dagbladet, 12 maj 2002.

- Stig Björkman, Torsten Manns och Jonas Sima, Bergman om Bergman.

- Ingmar Bergman, "Filmen om Birgitta-Carolina", Stockholms-Tidningen, 18 mars, 1949.

- Olivier Assayas och Stig Björkman, Tre dagar med Bergman.

- Ingmar Bergman, Laterna magica, Stockholm: Norstedts, 1987.

- Bergmans lista / Bergman's List, Göteborg: Filmkonst, 1994.

- Bergmans 1900-tal: En hyllning till svensk film, från Victor Sjöström till Lukas Moodysson, Göteborg: Göteborg Film Festival, 2000.

- Ingmar Bergman, Bilder, Stockholm: Norstedts, 1990.

- Ingmar Bergman, Kommentar till Serie Ö, Cinemateket/Svenska Filminstitutet, 1973.

Some of the directors Bergman has voiced a public opinion (there are more of course – Fassbinder, Renoir, von Trotta ... we'll expand the list as we go along).

Michelangelo Antonioni

The fact that Antonioni passed away the same day as Bergman, 30 July 2007, was not the only thing they had in common. Other comparisons would be similar themes such as the role of women in urban upper middle class, or Monica Vitti's and Gunnel Lindblom's hairdos in the sixties. Bergman's own relationship to Antonioni was two-edged:

He's done two masterpieces, you don't have to bother with the rest. One is Blow-Up, which I've seen many times, and the other is La Notte, also a wonderful film, although that's mostly because of the young Jeanne Moreau. In my collection I have a copy of Il Grido, and damn what a boring movie it is. So devilishly sad, I mean. You know, Antonioni never really learned the trade.

Robert Bresson

With his ascetic style and interest in religious matters, Bresson is a filmmaker with which many Bergman critics have wanted to compare him. When Bergman himself compared Prison with Bresson's Mouchette, the score Bergman–Bresson was 0–1:

But while Prison is full of quirks and divagation and coquetry and jumps about all over the place, Mouchette is clear as daylight. It’s a pure work of art.

And he continues:

I'm also tremendously fond of The Diary of a Country Priest, one of the most remarkable works ever made. My Winter Light was very much influenced by it.

Marcel Carné

It's not hard to see how the young Bergman was deeply influenced by the foremost director of French film noir. Le Quai des Brumes is on Bergman's list of best films of all times. Of all his many statements on Carné, we choose an unpublished journal entry from 1945:

Have been to the movies and seen Le Quai des Brumes, Marcel Carné's profound and bitter masterpiece. Feel like flyspeck on a window. This is cinema when it is art. How has he done it? Simple, almost meagre, but it is alive, alive and vibrating each second, it is cinema in its highest and purest form where everything is working.

Federico Fellini

Fellini and Bergman were supposed to make an omnibus film together once. Of this, nothing came out (more than a script which, however, is preserved in the Ingmar Bergman Archives). But they remained friends and were obviously deeply sympathetic to one another.

I spent a lot of time in the studio and saw him work. I loved him both as a director and as a person, and I still watch his movies, like La Strada and that childhood rememberance – what's that called again?

Jean-Luc Godard

By many (including, though it seems like professional misconduct, parts of the editorial staff of ingmarbergman.se) praised as the greatest filmmaker of all times. Not so by Bergman:

I've never gotten anything out of his movies. They have felt constructed, faux intellectual and completely dead. Cinematographically uninteresting and infinitely boring. Godard is a fucking bore.

Alfred Hitchcock

Possibly the most well-known filmmaker of all times and definitely one of the most influential. Bergman's admiration of him began early, actually before he was canonised by the French.

Hitchcock har gjort en vägande insats då det gällt att revolutionera filmens teknik inåt mot ett ändamålsenligare och mer komprimerat förfarande. För min del tror jag att hans resultat på detta område så småningom ska gå upp för filmens teoretiker för att dessa må placera honom på rangplats bland föregångsmännen där han rätteligen hör hemma.

Akira Kurosawa

As Fellini part of Bergman's generation, and another of those filmmakers he is often compared. Perhaps not in terms of style or subject as much as both are examples of the director as star in the 50s and 60s. Bergman admired him a lot.

Now I want to make it plain that Virgin Spring must be regarded as an aberration. It's touristic, a lousy imitation of Kurosawa. At that time my admiration for the Japanese cinema was at its height. I was almost a samurai myself!

F. W. Murnau

One of the silent eras most celebrated directors, both for his German and American works. Bergman agrees.

Then you have Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and his "The Last Laugh" with Emil Jannings, which doesn't have any titles but tells the story in images altogether, with a wonderful dynamics and sensualism in the imagery. And his "Faust" with Jannings and Gösta Ekman in the title role and the masterpiece "Sunrise". Three remarkable films telling us that Murnau [...] had come a long way creating an original and unique way of making movies.

Roberto Rossellini

Many of Bergman's early films were markedly influenced by neorealism in general and Rossellini in particular. But Rossellin's somewhat later work, such as the low key marriage drama Viaggio in Italia (1954), also seem to have been important sources of inspiration throughout Bergman's career.

Rossellini's films were a revelation – all that extreme simplicity and poverty, that greyness.

Victor Sjöström

The most well-known filmmaker of the Swedish silent era was also an actor, not least in not one but two of Bergman's films. He was also Bergman's absolute idol. Besides The Phantom Carriage (often nominated by Bergman as best film of all times), he often mentions another of Sjöström's films:

Ingeborg Holm is still true and gripping; remarkably modern. If run at its proper speed, which is 16 frames a second, it is photographic and scenically quite perfect.

Andrei Tarkovsky

Another of those filmmakers with which Bergman is often compared. And for good reasons; they were also each other's idols.

When film is not a document, it is a dream. That is why Tarkovsky is the greatest of them all. He moves with such naturalness in the room of dreams. He doesn't explain. What should be explained anyhow? He is a spectator, capable of staging his visions in the most unwieldy but, in a way, the most willing of media.

Orson Welles

Best known for his debut Citizen Kane, and by many hailed as one of the greatest directors of all times. As in the case of Godard, Bergman doesn't agree:

For me he's just a hoax. It's empty. It's not interesting. It's dead. Citizen Kane, which I have a print of – is all the critics' darling, always at the top of every poll taken, but I think it's a total bore.

Bo Widerberg

Second most well-known of Bergman's contemporary Swedish colleagues. Never too impressed with the more successful Bergman, who replied with patronising, fake high-mindedness.

The first time I saw Elvira Madigan when it came out in 1967 I actually didn't think it was anything special. I think it had a lot to do with the fact that Bo Widerberg at that time couldn't open his mouth without saying something disparaging about me. We had practically never met. But he wrote a book where he aggressively attacked me and I could never understand why. I actually thought he was an extremely good director, not for theatre but for film.

I saw Elvira Madigan again last summer when the newly restored version was ready and I saw it was a masterpiece. It is a film that is alive at each moment.

[…]

I could naturally choose Raven's End (Kvarteret Korpen). That is his masterpiece, an impeccable film. But it is Elvira Madigan because it is such a beautiful film. I think it is a pity that Bo and myself were never on speaking terms and that Bergman and Widerberg remained an unsolved complication.

World's greatest films according to Bergman (1994)

The Circus (Charles Chaplin, USA 1928)

Port of Shadows (Quai des brumes, Marcel Carné, France 1938)

The Conductor (Dyrygent, Andrzej Wajda, Poland 1979)

Raven's End (Kvarteret Korpen, Bo Widerberg, Sweden 1963)

The Passion of Joan of Arc (La passion de Jeanne d'Arc, Carl Th. Dreyer, France 1927)

The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen, Victor Sjöström, Sweden 1921)

Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, Japan 1951)

The Road (La Strada, Federico Fellini, Italy 1954)

Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, USA 1950)

Two German Sisters (Die bleierne Zeit, Margarethe von Trotta, BRD 1981)

Andrei Rublev (Andrei Tarkovsky, Soviet Union 1969)

Sweden's greatest films according to Bergman (2000)

The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen, Victor Sjöström, 1921)

The Atonement of Gosta Berling (Gösta Berlings saga, Mauritz Stiller, 1924)

Rågens rike (Ivar Johansson, 1929)

Söderkåkar (Weyler Hildebrand, 1932)

Karl Fredrik Reigns (Karl Fredrik regerar, Gustaf Edgren, 1934)

Karriär (Schamyl Bauman, 1938)

Dollar (Gustaf Molander, 1938)

Ett brott (Anders Henrikson, 1940)

Pengar - en tragikomisk saga (Nils Poppe, 1946)

Den allvarsamma leken (Rune Carlsten, 1945)

Only a Mother (Bara en mor, Alf Sjöberg, 1949)

Flicka och hyacinter (Hasse Ekman, 1950)

The Flute and the Arrow (En djungelsaga, Arne Sucksdorff, 1957)

Elvira Madigan (Bo Widerberg, 1967)

My Sister My Love (Syskonbädd 1782, Vilgot Sjöman, 1966)

Here's Your Life (Här har du ditt liv, Jan Troell, 1966)

Som natt och dag (Jonas Cornell, 1969)

Harry Munter (Kjell Grede, 1969)

Äppelkriget (Tage Danielsson, 1971)

Vem älskar Yngve Frej? (Lars Lennart Forsberg, 1973)

Det sista äventyret (Jan Halldoff, 1974)

The Magic Flute (Trollflöjten, Ingmar Bergman, 1975)

Giliap (Roy Andersson, 1975)

Långt borta och nära (Marianne Ahrne, 1976)

A Decent Life (Ett anständigt liv, Stefan Jarl, 1979)

Children's Island (Barnens ö, Kay Pollak, 1980)

Our Life is Now (Mamma, Suzanne Osten, 1982)

The Simple-Minded Murderer (Den enfaldige mördaren, Hans Alfredson, 1982)

Midvinterduell (Lars Molin, 1983)

My Life as a Dog (Mitt liv som hund, Lasse Hallström, 1985)

Amorosa (Mai Zetterling, 1986)

The Miracle in Valby (Miraklet i Valby, Åke Sandgren, 1989)

Spring of Joy (Glädjekällan, Richard Hobert, 1993)

Potatishandlaren (Lars Molin, 1996)

Show Me Love (Fucking Åmål, Lukas Moodysson, 1998)

Bergman's best according to Bergman (1990)

Today, I feel that in Persona – and later in Cries and Whispers – I had gone as far as I could go. And that in these two instance, when working in total freedom, I touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover.

Bergman's worst according to Bergman (1974)

Ship to India

Summer Interlude (later reassessed)