Strindberg in Bergman

Exclusive essay by Professor Egil Törnqvist on August Strindberg's great influence on Bergman – and (in a manner of speaking) vice versa.

Strindberg in Bergman

August Strindberg, Ingmar Bergman claimed, was his companion through life (Björkman 23). Already at the age of twelve he was acquainted with Strindberg’s oeuvre (Bergman 2001:11), and a year later he bought his Collected Works, 55 vols, in John Landquist’s annotated edition (Timm 346). Bergman soon considered Strindberg his household god. Even if he did not always share his views, he felt a great affinity with him. Strindberg, he said, “expressed things which I’d experienced and which I couldn’t find words for” (Björkman 24).

Already in the nursery little Ingmar staged plays by Strindberg in his puppet theatre. Later, as a student of literature at Stockholm University, he attended lectures on Strindberg’s dramas by Martin Lamm, the leading Strindberg scholar at the time. For him he wrote a paper comparing Strindberg’s pilgrimage playThe Keys of Heaven with his Dream Play (Timm 42f.), a paper which reads “like a prompt copy for a stage production” (Steene 70)[1] not surprisingly since by this time Bergman had begun staging plays.

In his lifetime Bergman directed eleven Strindberg plays for the stage, eight for radio and two for television. He was responsible for altogether twenty-eight Strindberg productions. Like Olof Molander, his predecessor as leading Strindberg director, he often returned to the same plays. He thus produced A Dream Play and The Ghost Sonata four times, The Pelican three times and Miss Julie, Playing with Fire and Stormy Weather twice.[2]

Like Molander he showed a preference for the late, so-called post-Inferno dramas.

Molander’s Strindberg productions made an indelible impression on Bergman:

First it was The Dream Play. Night after night I stood in the wings and sobbed and never really knew why. After that came To Damascus, The Saga of the Folkungs, and The Ghost Sonata. It is the sort of thing you never forget and never leave behind, especially not if you happen to become a director and least of all if you […] direct a Strindbergian drama. (Sjögren 38)

Aware of the cinematic qualities of The Saga of the Folkungs, he considered making a film version of the play (Timm 346). Instead of doing so he eventually made the film The Seventh Seal. Like The Saga of the Folkungs, the film is set in the 14th century. As in the drama, people are afflicted by the plague. And as there, religion plays a central role. Moreover, the film is in part rather theatrical.

Verbal echoes of Strindberg’s plays can be found in several of Bergman films.[3]

“They were down in the stable yard one evening,” Jean reports in Miss Julie, referring to the breaking of the engagement between Julie and her fiancé. “I saw them in the stable yard,”says Fredrik in Smiles of a Summer Night, referring to his wife Anne who has just eloped with his son Henrik. Miss Julie nostalgically recalls “childhood memories of Midsummer days with the church garlanded with birch trees and lilac.” Märta in Winter Light recalls summertime, ”the birch woods. The smell of jasmine” and the hymn connected with the beginning of the school vacation to all Swedes. In Strindberg’s Dance of Death I the Captain who has just suffered a heart attack asks Curt: “Do you think I’m going to die?” Curt answers with black humor: “You will as everybody. There will be no exception made in your case.” Cohen (437, note 14) has noted the similarity between this verbal exchange and the one in The Seventh Seal between Skat and Death. Skat, the actor, has climbed a tree with the intention to take a nap there, protected from animals in the forest. Suddenly he discovers that Death is sawing at the tree. Like Strindberg’s Captain he begins to fear for his life.SKAT: […] Aren’t there any special rules for actors?

DEATH: No, not in this case.

SKAT: No loopholes, no exceptions?

No, Death goes on sawing. We are all mortal. Without exceptions.

With his To Damascus Strindberg created the first subjective drama. An overwhelming part of this trilogy is a projection of the protagonist’s inner life. The varying locations and weather conditions mainly represent his varying states of mind. (Bergman combined the first two parts of the trilogy in a production at Dramaten in 1974.) The subjective scenery of To Damascus can be sensed in some of Bergman’s films, tempered by the realism of the medium. The barren island in Through a Glass Darkly and the frosty landscape in The Communicants, in the U.S. freely entitled Winter Light, are two examples.

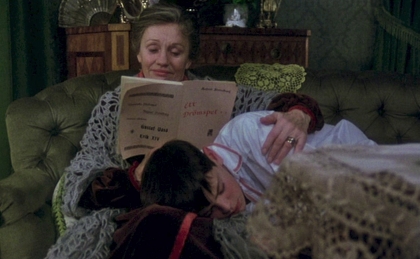

The diffuse borderline between dream and reality found in To Damascus and other plays by Strindberg, resulting in a feeling that life is a dream, is found in much of Bergman’s work as well. Bergman clearly indicates this when, at the end of Fanny and Alexander, he has Helena Ekdahl, once a praised actress, read from Strindberg’s famous “Note” to A Dream Play: “Everything can happen, everything is possible and probable. Time and place do not exist; on an insignificant basis of reality the imagination spins and weaves new patterns.” This passage is not only a key to Bergman’s last feature film. It is a key also to other works by him, on stage and screen. The interweaving of reality and fantasy, objectivity and subjectivity, runs through his entire work.

The gray crotcheted shawl worn by Helena is borrowed from the shawl the Doorkeeper hands over to Agnes alias Indra’s Daughter in A Dream Play. At the end of Fanny and Alexander Alexander’s mother Emilie suggests that she and Helena should act in this recently published drama.[4] The shawl indicates that Helena would then play the part of the Doorkeeper and Emilie the part of Agnes.

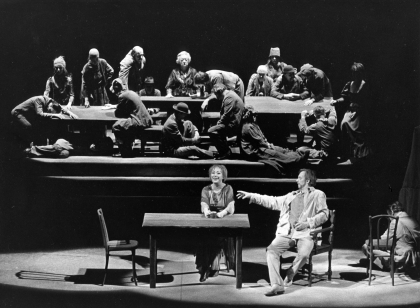

Agnes (Malin Ek) and the Mother (Aino Taube) in Bergman's staging of A Dream Play, Royal Dramatic Theatre, 1970.

Photo: Beata Borgström

Strindberg called some of his late dramas chamber plays. In drama, he writes in his Memorandum to the Members of the Intimate Theatre (1908), “we seek the strong, significant motif, but with limitations. [...] No predetermined form is to limit the author, because the motif determines the form.” In a letter the year before he spoke with regard to the chamber plays about “the intimate in form, a restricted subject, treated in depth, few characters, large points of view.”

Bergman has been called “the most energetic pursuer of the Strindbergian chamber play” (Sjöman 13). He applied Strindberg’s term to some of his films:

Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light and The Silence and Persona I have called chamber plays. They are chamber music. That is, you cultivate a number of motifs with an extremely limited number of voices and characters. You extract the backgrounds. You place them in a kind of haze. You create a distillation. (Björkman 168, trans. improved)

The Ghost Sonata ends with a ‘coda,’ a swift recapitulation of earlier themes and an execution: the belief in a benevolent God which is the prerequisite for the Student’s intercession for the Young Lady. In the same way, Through a Glass Darkly ends with a ‘divine proof’--the idea that God is love--and this, says Bergman, forms “the actual coda in the last movement” (Sjöman 24). By its very title The Ghost Sonata implies a relationship with the sonata form. The title of Autumn Sonata has the same implication, anticipated when Bergman played with the idea of calling Persona “A Sonata for Two Women” (Svensk Filmografi 6:289). Even more explicit is the title of his last teleplay, Saraband, referring to the fourth movement in Bach’s Solo Cello Suite No. 5 in C minor, a fragment of which forms the play’s musical leitmotif.

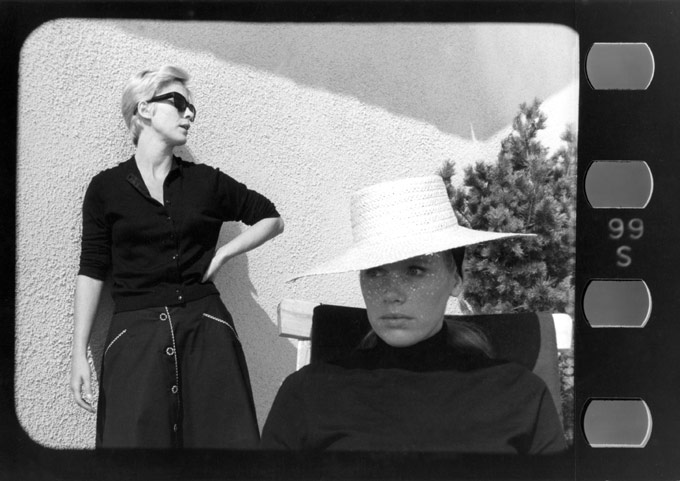

Even Strindberg plays never directed by Bergman have proved to be influential. The Saga of the Folkungs is one example, The Stronger is another. In this quart d’heure we are confronted with two actresses, one of whom refuses to speak. Miss Y, the silent character, has had and possibly still has an affair with the husband of the speaking character, Mrs X. When the play opens, Mrs X is not aware of this. But as she recapitulates past events, she gradually discovers Miss Y’s role as mistress to her husband.

Bergman’s Persona deals with an actress, Elisabet, who suddenly stops talking. Her psychiatrist makes it clear that “this silence she imposes on herself is unneurotic. It’s a strong person’s form of protest” (Bergman in Björkman 211) against role-playing on and off stage. Elisabet’s dilemma was Bergman’s own at the time. In a TV interview he later said that his distrust of words was then so deep that he felt that “the only form of truth is silence.”[5]

Alma (Bibi Andersson) and Elisabet (Liv Ullmann) in Persona.

Photo: Sven Nykvist © AB Svensk Filmindustri

In her comparison of the silent characters in The Stronger and Persona, Susan Sontag (268) writes that “the one who talks, who spills her soul, turns out to be weaker than the one who keeps silent. Language is presented as an instrument of fraud and cruelty.” John Simon (306f.), commenting on the two works, writes with regard to the silent characters: “silence is, in the final reckoning, vampirism: a vacuum into which the other person’s, the speaker’s, lifeblood ebbs as surely as if it were being sucked.” But is the silent character really more honest than the speaking, as Sontag seems to suggest? The psychiatrist in Persona questions this when telling Elisabet: “I think you should keep playing this part until you’ve lost interest in it.When you’ve played it to the end, you can drop it as you drop your other parts.” This agrees with Bergman’s own view at the time. In the interview just referred to he continued: “going a step further, I discovered that it [the silence], too, was a kind of role, also a kind of mask” (Gado 321). Whether speaking or not we keep playing roles.

In her comparison of the silent characters in The Stronger and Persona, Susan Sontag (268) writes that “the one who talks, who spills her soul, turns out to be weaker than the one who keeps silent. Language is presented as an instrument of fraud and cruelty.” John Simon (306f.), commenting on the two works, writes with regard to the silent characters: “silence is, in the final reckoning, vampirism: a vacuum into which the other person’s, the speaker’s, lifeblood ebbs as surely as if it were being sucked.” But is the silent character really more honest than the speaking, as Sontag seems to suggest? The psychiatrist in Persona questions this when telling Elisabet: “I think you should keep playing this part until you’ve lost interest in it. When you’ve played it to the end, you can drop it as you drop your other parts.” This agrees with Bergman’s own view at the time. In the interview just referred to he continued: “going a step further, I discovered that it [the silence], too, was a kind of role, also a kind of mask” (Gado 321). Whether speaking or not we keep playing roles.

In The Seventh Seal there is a character who is nameless like the Milkmaid. She is simply called “the girl.” In the film she has only one speech, close to the end when she as one of six is being fetched by Death. She then repeats Christ’s last words on the cross: “It is finished” (Joh. 19:30). Like the Milkmaid she is an altruistic woman of deeds, prepared to help even the plague-smitten thief Raval. To this we may add another aspect. It is hardly accidental that the silent character in the film is the only one who fully accepts, even welcomes Death.

Another Bergmanian counterpart of the Milkmaid is Anna, the housemaid in Cries and Whispers. Anna, it says in the script,

is very taciturn, very shy, unapproachable. But she is ever-present – watching, prying, listening. Everything about Anna is weight. Her body, her face, her mouth, the expression of her eyes. But she does not speak; perhaps she does not think either.

Kari Sylwan as the Milkmaid in Bergman's staging of The Ghost Sonata, Royal Dramatic Theatre, 1970.

Photo: Beata Borgström © Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Statens musikverk

Like the Milkmaid, Anna embodies altruism. And just as the Milkmaid’s profession as we have seen indicates her nurturing function, so Anna’s role of housemaid is a sign of her willingness to serve--feel compassion for--her fellow men. In both the play and the film, the person who is socially the most unassuming is ethically the most worthy. Characteristically, Bergman cast the same actress in both parts and provided her with virtually the same costume.

Anna (Kari Sylwan) praying for her dead daughter in Cries and Whispers (1972).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

Anna is the only one who hears Agnes’s crying; who consoles her with the warmth of her maternal bosom; and who is willing to stay with her when she is dead.

In The Stronger Mrs X suggests that Miss Y’s silence is an expression of vampirism. “You have been sitting there,” she says, “drawing out of me all these thoughts that have been lying like raw silk in the cocoon.” In Persona the vampirism is shown directly. Elisabet sucks the blood from Alma’s wrist which, however, is voluntarily offered her.

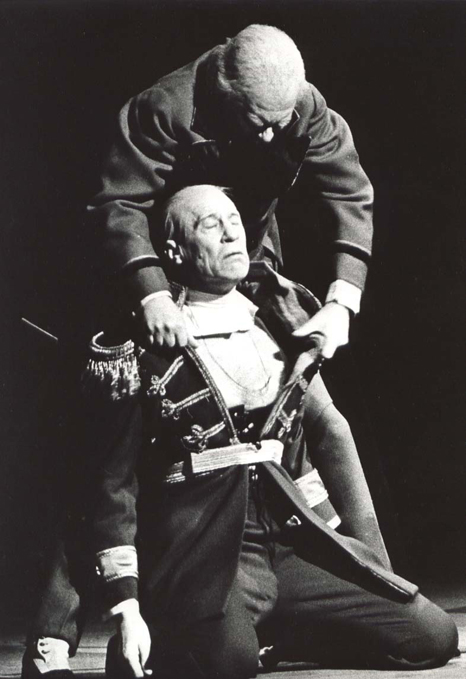

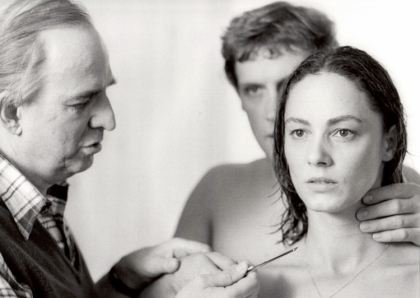

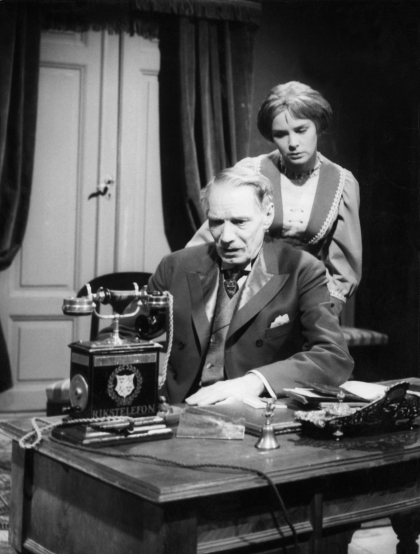

Bergman giving hands-on instruction to Toivo Pawlo (playing Hummel) in how to grasp The Student's (Mathias Henrikson) hand. Ghost Sonata, Royal Dramatic Theatre, 1973.

Photo: Beata Bergström.

The vampirism in Persona visualizes Elisabet’s mental attitude as experienced by Alma. A passage in The Ghost Sonata may have been a source of inspiration. As the Old Man, Hummel, early in this play takes hold of the Student’s hand, the latter cries out: “But let go of my hand, you’re taking all my strength away, you’re freezing my blood.” When Bergman rehearsed this sequence for his 1973 production of the play, he called Hummel’s gesture vampiric and demonstrated how the Old Man is here figuratively sucking the Student’s blood.

Scenes of unmasking occur in several of Strindberg’s dramas. In Creditors Gustaf, who has been married to Tekla, visits Adolf who is now married to her. For a long time Adolf remains unaware that his visitor is his wife’s former husband. When he shows Gustaf a photo of Tekla, Gustaf remarks: “Do you see the cynical expression about the mouth--which she never lets you see? Do you see the glances in search of a man who is not you?” In Bergman’s Cries and Whispers, Marie and the Doctor, her lover, are at one point standing before a mirror. Says the Doctor: “Your eyes cast quick, calculating glances. You sneer too often, Marie.” The two situations are quite similar. The photo and the mirror serve the same revelatory purpose.

A very spectacular scene of unmasking is found in the second act of The Ghost Sonata, where Hummel, after he has unmasked the Colonel, tells him: “Here come the guests--keep calm, now, and we’ll go on playing our old roles.”

Hummel literally unmasking the Colonel (Anders Ek) in Bergman’s 1973 production of The Ghost Sonata at the Royal Dramatic Theatre.

Photo: Beata Borgström © Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Statens musikverk

A similar pattern is found in Persona, where the blunt confrontation between Alma and Elisabet is followed at the end of the film by their return to a normal ‘masked’ existence. Elisabet, who has refused to speak for months, returns to her role as an actress, Alma to hers as a nurse when she puts on her uniform again.

The most common way to establish contact with our fellow men is through language. Yet like Strindberg, Bergman distrusts language as a means of communication in any deeper sense. We have already seen how Elisabet in Persona chooses muteness in the conviction that words equal lies. Taking Hummel’s remark in The Ghost Sonata to heart that languages are “codes” invented “to conceal the secrets of one tribe from the others,” Bergman often demonstrates how language rather than serve as a means of communication serves as a conscious or unconscious barrier. This idea is fundamental in The Silence, where the main characters are confronted with a language, construed by Bergman, which is as unintelligible to them as to us. The inability to understand the foreign language is here a metaphor for our inability to understand one another truly. While Anna in The Silence tries to communicate via the senses, her sister Ester, a professional translator, tries to do so via reason. In her attempt to understand the foreign language she is, like the Student in The Ghost Sonata, a seeker who tries to understand life intellectually.

The exam sequence in Wild Strawberries, where Sten Alman (Gunnar Sjöberg) is flunking Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström).

Photo: Louis Huch © AB Svensk Filmindustri

In the nightmarish exam scene of Wild Strawberries, professor emeritus Isak Borg, who has been a harsh examiner, finds himself in the position of his former students. It is now his turn to be harshly examined and to fail his exam. His failure is serious since the blackboard text Isak is unable to decipher tells what a doctor’s—read: man’s--primary duty is: to care for your fellow men. The sequence is a contamination of the Asylum scene in To Damascus I and the school scene in A Dream Play. In the former the Stranger is condemned for the wrongs he has done to his fellow men, in the latter the Officer, recently conferred doctor, finds himself returned to primary school. In Wild Strawberries we have a thematic counterpart of the school scene when young Sara tells Isak, as she holds a mirror in front of his face, that although he knows a lot, he knows in fact almost nothing—that is, about the essentials of life. When Tomas, the doubting priest in Winter Light sits down at one of the pupils’ desks in the local school, it is a discreet reminder that he, like Isak Borg and the Officer, needs to “mature” as it says in A Dream Play.

The unknown (Jan Olof Strandberg) in Bergman's 1974 staging of To Damascus, with beggars and cripples in the background.

Foto: Beata Bergström © Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Statens musikverk

The Officer in A Dream Play is intrigued by a door in the Theatre corridor “with airholes in the shape of a four-leaved clover.” What can be behind it? Noone has seen the door open and when it finally is opened, there is nothing to be seen behind it. The door separates the known from the unknown, this life from what is beyond it. Is there anything beyond life? Does the four-leaved clover promise a happy existence after death? Or is it treacherous? The Officer’s curiosity is universal. When the door in the Church scene leads to the sacristy, the four airholes are seen not as a four-leaved clover but as a cross. Suffering gives hope for heaven. As it says on Strindberg’s gravestone: “O crux ave spes unica” (O hail to the cross my only hope).

The four-leaved clover door has its counterpart in the leaf-patterned wall in Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly. Intrigued by the wallpaper, the mentally unstable Karin peeps through a rift in it and listens to angelic voices behind it indicating a benevolent God.

Karin (Harriet Andersson) hears voices behind the wallpaper in Through a Glass Darkly.

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

She becomes brutally disillusioned when the ‘God’ appears in the form of a spider-like helicopter which comes to fetch her to the mental hospital.

The connection between The Ghost Sonata and Cries and Whispers, by Bergman considered one of his best films, is striking. In the centre of the film, we find Agnes, “the intended owner of the estate” which is visualized in the film. In the script it says that Agnes, Christlike like her namesake in A Dream Play,

has vague artistic ambitions--dabbling in painting, playing the piano a little; it is all rather touching. No man has turned up in her life. [...] At the age of thirty-seven she has cancer of the womb and is preparing to make her exit from the world as quietly and submissively as she has lived in it. [...] She is very emaciated, but her belly has swollen up as though she were in an advanced stage of pregnancy. [...]

Agnes's painting is generously colorful and somewhat romantic. Her main subject is flowers.

Agnes resembles the Young Lady in The Ghost Sonata, the intended owner of the building seen on the stage. Like Agnes, the Young Lady suffers from cancer of the uterus (Törnqvist 2000:50f.). The Young Lady’s illness indicates that she is ”sick at the source of life,” to quote the Student, a victim of Original Sin. Just as the Young Lady is “withering away in [an] atmosphere of crime, deceit and falseness of every kind,” so Agnes is surrounded by faithlessness and emotional chill. Neither her mother, now dead, nor her sisters have given her the warmth she has longed for. Both Karin and Maria are unhappily married, both are unfaithful to their husbands, and both are anxious--as are their husbands--to show an immaculate social persona. Agnes cannot thrive in such surroundings. Her consolation is the servant Anna.

When Agnes has died the Chaplain, “enclosed in the black uniform of office,” prays for her. The opening is rhetorical:

May your Father in Heaven have mercy on your soul when you step into His presence. May He let His angels disrobe you of the memory of your earthly pain.

But he soon drops the traditional pattern, and despite the rhetorical anaphorae, the rest of his speech carries the note of sincere despair at the human condition:

If it is so that you have gathered our suffering in your poor body, if it is so that you have borne it with you through death, if it is so that you meet God over there in the other land, if it is so that He turns His face toward you, if it is so that you can then speak the language that this God understands, if it is so that you can then speak to this God. If it is so, pray for us. Agnes, my dear little child, listen to what I am now telling you. Pray for us who are left here on the dark, dirty earth under an empty and cruel Heaven. Lay your burden of suffering at God’s feet and ask Him to pardon us. Ask Him to free us at last from our anxiety, our weariness, and our deep doubt. Ask Him for a meaning to our lives. Agnes, you who have suffered so unimaginably and so long, you must be worthy to plead our cause.[6]

The end of the first part of the speech resembles the Student’s intercession for the dead Young Lady at the end of The Ghost Sonata: “may you be greeted by a sun that does not burn, in a home without dust....” The main part resembles the Poet’s appeal to Indra’s Daughter in A Dream Play: “Child of the gods, will you translate / our lament into language / the Immortal One understands.” The Chaplain’s prayer is crammed with questioning ‘ifs’ - as if he doubts the existence of a benevolent god. In line with this, the perspective of the introductory part is reversed. No longer praying that God take mercy on the dead woman, the Chaplain asks her to intercede by Him for the living. As for the author of A Dream Play, it is not the dead but the living who are pitiable.

In After the Rehearsal, Bergman’s alter ego Henrik Vogler is rehearsing his fifth Dream Play. The piece opens with a shot of the director seen from above. On the table in front of him is a green lamp, his prompt book and a green copy of A Dream Play in the familiar first Collected Works edition. In A Dream Play the green colour represents the hope mankind is constantly nourishing, a hope that always proves to be deceptive—until we are faced with the ultimate question: will our hope for a heaven after death come to nought or come true? The initial shot imitates the Prologue of the play that is on Vogler’s mind: Indra’s Daughter’s descendence to Earth. Likewise, his turning the light of the lamp next to him on and off reveals that the following passage of the play he is rehearsing is on his mind:

Officer sits down. [...] So! Rehearsals have begun! -The stage is now illuminated intermittently as if by the beam of a lighthouse.- What’s this? –In time with the flashes of light.- Light and dark; light and dark?

Daughter imitates him. Day and night; day and night!

In all its simplicity a striking image of life!

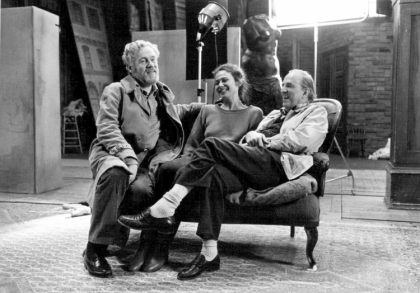

Erland Josephson, Lena Olin and Ingmar Bergman between takes in Bergman's 1983 television play After the Rehearsal.

Photo: Arne Carlsson © AB Svensk Filmindustri

In 1981 Bergman staged Miss Julie—then called merely Julie--together with Ibsen’s Doll’s House, called Nora, and his own Scenes from a Marriage at the Residenztheater in Munich. Jean and Julie, Torvald and Nora, Peter and Katarina represented three kinds of man-woman relations in what soon became known as the Bergman project. The part of Julie was intended for Bergman’s favourite actress, Christine Buchegger. But she fell seriously ill and had to be replaced by another actress. One year before this happened Bergman’s film Aus dem Leben der Marionetten (From the Life of the Marionettes) premiered. The secondary couple in Scenes from a Marriage, Peter and Katarina, now became the primary couple, with Christine Buchegger as Katarina.

Strindberg’s Miss Julie ends with Julie’s suicide offstage, most clearly indicated when Jean shows her how to do it.

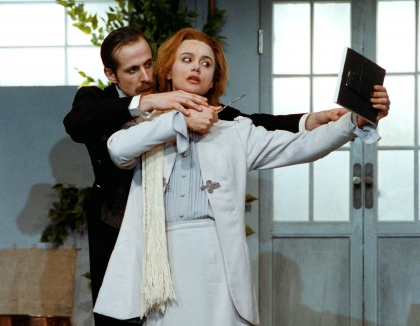

Julie (Lena Olin) and Jean (Peter Stormare) in Bergman's staging of Miss Julie, Royal Dramatic Theatre, 1985.

Photo: Bengt Wanselius

In From the Life of the Marionettes Peter and Katarina are about as unhappy in their marriage as their namesakes in Scenes from a Marriage. Seeking help, Peter sees a therapist, Mogens Jensen, who without his knowing it is Katarina’s lover. (We are reminded of the triangle in Creditors.) He tells Mogens of his recurrent dream in which he kills his wife. At the end of the film he kills a prostitute named Katarina. Like Jean in Miss Julie and Gustaf in Creditors he commits murder by proxy.

Bergman instructing Katarina (Christine Buchegger) and Peter (Robert Atzorn) in From the Life of the Marionettes (1980).

Photo: Lars Karlsson © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Wild Strawberries had its premiere in December 1957. A little more than two years later, on 22 January (Strindberg’s birthday) 1960 Bergman’s TV production of Strindberg’s Stormy Weather was broadcast in Scandinavia. Already in the documentary opening shots Bergman makes it clear that the chamber play is set in Östermalm, the opulent part of Stockholm where Strindberg lived when he wrote it—and where Bergman came to live many years later.[7]

Like the Gentleman in Stormy Weather, Isak Borg in Wild Strawberries is an old, self-centered man. Both men have unhappy marriages behind them. Both imagine that they have reached a stage in life where loneliness can be calmly accepted. Isak claims that he has voluntarily withdrawn from social company and for the Gentleman the expression “the peace of old age” has become a mantra. Yet neither of them has chosen to live as a hermit. Both live in apartment houses and are consequently surrounded by other people. And both have a housekeeper who functions more or less as a substitute wife. In short, both men lead an existence wich is bordering on but not identical with that of a hermit, a choice indicative of their vacillating attitude to loneliness and togetherness respectively. Like the Gentleman, Isak has the habit of strolling “along a broad, tree-lined boulevard,” an indication that both men cherish an existence of observation and independence.[8]

Uno Henning as The Gentleman and Mona Malm as Louise in Bergman's 1960 TV production of Stormy Weather.

© SVT Bild

Occasionally a piece of property called for in a Strindberg play is recycled in a Bergman film. We have already seen how Agnes’s shawl in A Dream Play returns in Fanny och Alexander. Similarly, the chess-table and the mantelpiece with its candelabra in Stormy Weather—both highly symbolic-- return in Isak Borg’s study in Wild Strawberries. The first act of The Ghost Sonata shows an apartment house as seen from the street. In one of the windows of the drawing-room “a white marble statue of a young woman […] surrounded by palms, lit by sunlight” is seen. The statue represents the Mummy as a young woman and suggests a virginal Eve in the garden of Eden. In his 1973 production of the play at Dramaten Bergman had the same actress, Gertrud Fridh, play the Young Lady and the Mummy. By this arrangement the idea that the Mummy has once been a beautiful young woman was linked with the corresponding idea that the Young Lady is doomed to end up as a ‘mummy.’ The idea was accentuated by placing both women next to the statue in contrasting light.

Gertrud Fridh as The Young Lady in Bergman's staging of The Ghost Sonata, Royal Dramatic Theatre 1973.

Photo: Beata Borgström © Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Statens musikverk

The statue in The Ghost Sonata later appears in Helena Ekdahl’s elegant drawingroom in Fanny and Alexander, here again sunlit and surrounded by palms. The symbolism is the same as in The Ghost Sonata. In either case we are confronted both with individual youth--in this case the Mummy’s--and collective youth, of mankind: Eve before the Fall. Suddenly the statue moves its left arm. It has come alive. In the next shot a skeleton—you see only a skull--is stealing behind the palms towards the statue. Via Alexander’s imaginative mind we witness how the human body will eventually become a skeleton, how life will turn into death.[9]

Moving statue in Fanny and Alexander (1982).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

At the end of Strindberg’s The Pelican Fredrik sets fire to the apartment where he and his sister Gerda have been virtually locked up and starved by their mother. As they succumb to he flames warming them after a life in the cold, Fredrik hallucinates that his family is leaving for the annual summer vacation in the archipelago. Like the dead Young Lady’s voyage at the end of The Ghost Sonata, Fredrik’s voyage will this time take him to the Isle of the Dead. The play’s final line is his ecstatic ”Now summer vacation begins!”, a line that symbolically expresses his hope for a better existence after death.

To Strindberg the Stockholm archipelago was as close as you could get to paradise on earth. Bergman too loved islands; during the latter part of his life he was to live on one, Fårö, which for him has literally become an Isle of the Dead; both he and his beloved Ingrid rest there together in a grave. When Isak Borg at the end of Wild Strawberries after a long day’s journey is about to fall asleep, he has a vision of his parents welcoming him from an environment reminiscent of an archipelago. As in the end of The Pelican, this vision signifies not only a happy childhood memory. It also expresses Isak’s hope for a reunion with his parents in after-life.

In Saraband, Bergman’s last screen production, Carl expresses the hope that he and his dead wife Anna will reunite in an after-life. Carl voices Bergman’s own hope that he would meet his deceased wife Ingrid in a life after death. Carl’s and Ingmar’s hopes hark back not only to Isak Borg’s final vision in Wild Strawberies but also to the Student’s intercession for the dead Young Lady and his vision of the blessed Isle of the Dead at the end of The Ghost Sonata as well as to Fredrik’s vision at the end of The Pelican. Rarely has the intense existential feeling expressed in Strindberg’s two plays found such a sonorous reverberation as in Bergman’s two screen works.

Bergman once pointed out: “Between my job at the theater and my job in the film studio it has always been a very short step indeed” (Björkman 99). The step seems to have been particularly short between Strindberg’s plays and Bergman’s films.

Egil Törnqvist is Professor Emeritus at the department of skandinavistics, Universiteit van Amsterdam. He is author of a dozen-odd books on Ingmar Bergman and August Strindberg. His latest monography is the bilingual Drama as Text and Performance: Strindberg's and Bergman's Miss Julie / Drama som text och föreställning: Strindbergs Fröken Julie och Bergmans (Amsterdam: Pallas Publications, 2012).

[1] For ample references to the Strindberg-Bergman relationship, see the index, 1125. See also Törnqvist 2003 (under Strindberg in index) and 2009.[2] He also began rehearsing The Dance of Death I but the production broke down when Bergman was arrested because of suspected tax fraud. (The case was later dropped.) A plan to resume the production was aborted because of the terminal illness of one of the leading actors (Steene 952ff.).

[3] Cohen has listed some of them. See his index under Strindberg, 507.

[4] Bergman here deviates from reality. The end of Fanny and Alexander takes place in May 1909. A Dream Play was published already in 1902 together with two other Strindberg plays and was first produced in 1907. The play did not exist as a separate publication in 1909.

[7] Strindberg lived for some years in a modern apartment house facing Karlaplan and Karlavägen. The address was Karlavägen 40. This house was pulled down in 1969 when it was replaced by an apartment house where Bergman came to live during his stays in Stockholm. In his radio production of Stormy Weather 1999 Bergman refers, for the initiated, to this spatial connection when he has the Brother call for a taxi to “Karlavägen 40.”

Sources

- Bergman, Ingmar. 1960. Four Screenplays: Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, The Magician. Trans. Lars Malmström and David Kushner. London/New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Bergman, Ingmar. 1963. En filmtrilogi: Såsom i en spegel, Nattvardsgästerna, Tystnaden. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Bergman, Ingmar. 1966. Persona. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Bergman, Ingmar. 1973. Filmberättelser 3: Riten, Reservatet, Beröringen, Viskningar och rop. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Bergman, Ingmar. 1994. Femte akten. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Björkman, Stig, Torsten Manns, Jonas Sima. 1970. Bergman om Bergman. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Cohen, Hubert I. 1993. Ingmar Bergman: The Art of Confession. New York: Twayne.

- Cowie, Peter. 1992. Ingmar Bergman: A Critical Biography. London: Andre Deutsch.

- Gado, Frank. 1986. The Passion of Ingmar Bergman. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Johns, Marilyn E. 1978. Journey into Autumn: Oväder and Smultronstället. Scandinavian Studies, Vol. 50, No. 3.

- Simon, John. 1972. Ingmar Bergman Directs. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

- Sjögren, Henrik. 1968. Ingmar Bergman på teatern. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Sjöman, Vilgot. 1963. L136: Dagbok med Ingmar Bergman. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Sontag, Susan. 1975. Persona: The Film in Depth. I Stuart M. Kaminsky, ed. Ingmar Bergman: Essays in Criticism. London: Oxford University Press.

- Steene, Birgitta. 2005. Ingmar Bergman: A Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Strindberg, August. Samlade Verk. 1981– . Red. Lars Dahlbäck/Per Stam. Stockholm: Almqvist&Wiksell/Norstedt.

- Svensk filmografi. 1977. Vol. 6. Stockholm: Svenska Filminstitutet.

- Timm, Mikael. 2008. Lusten och demonerna: Boken om Bergman. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Törnqvist, Egil. 1973. Bergman och Strindberg: Spöksonaten – drama och iscensättning, Dramaten 1973. Stockholm: Prisma.

- Törnqvist, Egil. 1994. Long Day's Journey into Night: Bergman’s TV Version of Oväder Compared to Smultronstället. I Kela Kvam, ed. Strindberg's Post-Inferno Plays. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

- Törnqvist, Egil. 2003. Bergman’s Muses: Æsthetic Versatility in Film, Theatre, Television and Radio. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Compan, Inc.

- Törnqvist, Egil. 2009. Bergman’s Strindberg. I Michael Robinson, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Strindberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.