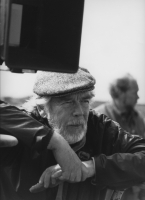

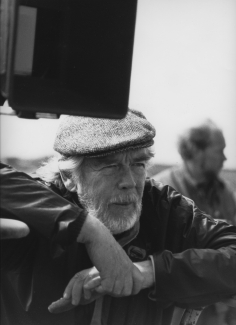

Sven Nykvist

One of the world's foremost cinematographers, whose poetic use of light illuminated many of Ingmar Bergman's greatest films, Nykvist replaced Gunnar Fischer as Bergman's cinematographer of choice in the early 1960s.

Sven Nykvist

One of the world's foremost cinematographers, whose poetic use of light illuminated many of Ingmar Bergman's greatest films, Nykvist replaced Gunnar Fischer as Bergman's cinematographer of choice in the early 1960s.

My whole young adulthood was full of dazzling cinematic images that he was responsible for. It was an honor to have worked with him and a treat to have spent time in his company.

Woody Allen

About Nykvist

Born Sven Vilhem Nykvist on 3 December 1922 in Moheda, Kronobergs län, the son of non-conformist missionaries to Africa.

Nykvist spent his childhood in Sweden whilst his parents spent four-year stints in Africa. In their parents' absence, the Nykvist children lived in a Christian children's home in Stockholm. His parents moved back to Sweden for good when Sven was ten years old, settling in Rönninge just outside Stockholm. In secondary school he met a number of people who would later make a name for themselves in Swedish theatre and cinema, including Keve Hjelm, Kenne Fant and Torsten Lilliecrona.

Having developed an interest in filming at an early age, Nykvist was just 15 years old when he bought his first 8mm camera. His father shared his interest, allowing his son to study the subject despite its somewhat suspect reputation in the nonconformist circles in which the family moved. Prior to his 20th birthday, Nykvist got a job in 1941 with Sandrews as an assistant cameraman. Thus from an early age he came into contact with many of the leading names of Swedish cinema of the day: Hasse Ekman, Alf Sjöberg (a major influence on picture composition, according to Nykvist himself), Viveca Lindfors, Lorens Marmstedt and Julius Jaenzon (the cameraman for Victor Sjöström's silent films).

Nykvist made his debut as principal cinematographer with the hugely popular Barnen från Frostmofjället in 1945. During the 1940s and 50s he made some 30 or so features with directors including Ivar Johansson, Arne Mattsson (known by Nykvist as 'the dolly' for his love of lengthy takes) and Alf Sjöberg. He also made documentaries, including one celebrated film about Albert Schweitzer that required him to spend a considerable time in the Congo, in the footsteps of his parents.

In 1953 Nykvist shot the interiors for Sawdust and Tinsel, pulling off an amazing 180-degree pan of Åke Grönberg holding a pistol. This shot made such an impression on Bergman that he is reputed to have said that he wanted Nykvist for all his films going forward. However, when Bergman was about to make Dreams, Nykvist was on Iceland working with Mattsson on Salka Valka. And by the time he came back, Bergman had left Sandrews for Svensk Filmindustri, thereby resuming his partnership with Gunnar Fischer.

Nykvist resumed his work with Bergman on The Virgin Spring in 1960, when Gunnar Fischer was on secondment to Walt Disney Pictures. Sandrews had released Nykvist to make the film on condition that they could borrow Bibi Andersson, contracted at the time to Svensk Filmindustri.

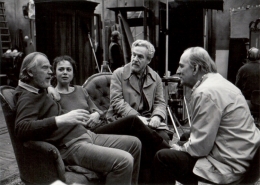

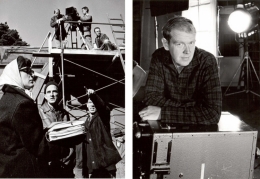

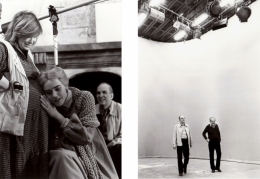

From Through a Glass Darkly onwards, Nykvist replaced Gunnar Fischer as Bergman's cinematographer of choice. Their pioneering work concentrated on the emotional impact of lighting and colour levels, Winter Light and Cries and Whispers being perhaps the most obvious examples of this approach. Having won an Oscar for best cinematography with the latter film, Nykvist, who had worked abroad only sporadically since the 1950s, found himself in increasing demand outside Sweden. The many celebrated directors with whom he worked include Louis Malle, Roman Polanski, Paul Mazursky, Volker Schlöndorff, Peter Brook and Woody Allen.

However, working in Hollywood was not so straightforward as might be expected, requiring membership of the ASC (American Society of Cinematographers). Following an interview he became the first European to be accepted into the society. Furthermore, working in America, regulations did not permit him to operate the camera himself, i.e. to sit at the camera and see the image in the viewfinder. This required a major adjustment for Nykvist, who in almost 80 films had always operated the camera himself.

His work with Bergman continued parallel to his international career, and it was another Bergman film, Fanny and Alexander, that won him his second Oscar.

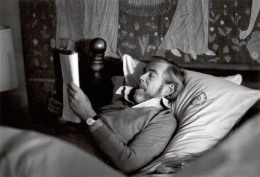

Nykvist's ability to work quickly and efficiently with natural lighting, his simple yet intensely expressive images, and his humble, reflective personality made him one of the most sought-after cameramen in the world. During the 1990s he worked with directors including Lasse Hallström in What's Eating Gilbert Grape and Liv Ullmann in Kristin Lavransdatter and Private Confessions. He was the cameraman for the directorial debuts of both Erland Josephson and Max von Sydow, and he also directed a film together with Josephson and Ingrid Thulin. Nykvist has also directed features entirely by himself, most notably the Oscar-nominated Oxen in 1991, in which Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann both acted.

In 1998 Sven Nykvist was diagnosed with aphasia and retired from the cinema. The year before he had made Woody Allen's Celebrity, his 123rd and final film. For 30 of his 55 years in the business, Sven Nykvist was one of the most celebrated and influential cinematographers in the world.

His son, Carl-Gustaf Nykvist, is himself a filmmaker who has made a documentary about his father, Light Keeps Me Company, in which several colleagues from Nykvist's films with Bergman also took part.

Sven Nykvist passed away 20 September 2006 in Stockholm.

Woody Allen commented on the death of Sven Nykvist as follows:

'I was greatly saddened to hear that Sven Nykvist died. He was a brilliant photographer and a wonderful man. My whole young adulthood was full of dazzling cinematic images that he was responsible for. It was an honor to have worked with him and a treat to have spent time in his company.'

Sources

- Sven Nykvist & Bengt Forslund, Vördnad för ljuset: om film och människor, (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1997).