Behind the Mirror

As subject matter, metaphors and symbols, mirrors abound in Bergman.

"Look at yourself in the mirror. You are beautiful. Perhaps more so than in our time. But you've changed."The doctor in Cries and Whispers (1973).

Behind the Mirror

In a scene from Wild Strawberries (one of the best-known of all Bergman scenes) the elderly professor Isak Borg lies semi-recumbent among grass and wild strawberries in a forest grove. As if in a dream, he sees first love Sara sitting in front of him, holding a hand mirror up to his face. He doesn't want to look, but she insists:

The mirror here is a painful vehicle of self awareness: the glass mercilessly reflects the aspects of the self that the person reflected wishes to ignore. There are many similar scenes in Bergman, not only in his films. For example, in the article Ingmar's Self-Portrait (written in the same year Wild Strawberries was premiered) Bergman describes a situation in which he himself undergoes a similarly uncomfortable experience to that of Isak Borg: the mirror shows parts of ourselves that we are unwilling to acknowledge. As the early Bergman interpreter Marianne Höök so finely puts it: "The mirror is an opening in the wall of reality."

It is Maaret Koskinen, Professor of Film Studies at Stockholm University, who in her dissertation Spel och speglingar (Mirrors and Mirroring, Stockholm University, 1993), has demonstrated how the mirror motif is recurrent in Bergman. Others had noticed it before her, but only Koskinen has looked at (and into) all the mirrors that Bergman holds up for his characters and audiences.

The motif begins, as Koskinen observes, as early as Bergman's first film. In Crisis we see the middle-aged, impenitent Jenny observe her mirror image with the words: "You can't see from the outside, but beneath this face ... oh, my God!" Bergman's mirrors have already acquired x-ray qualities: they see more than we see – what lies behind the facial mask.

There are similar scenes in almost every Bergman film. In Thirst mirrors acquire their most important role thus far in his work, but it is in Summer Interlude that we find the first truly famous of Bergman's mirror scenes. There are many mirrors in the film, which according to the critic Leif Zern in his book Se Bergman (Stockholm: Norstedts, 1993) perform a double function: they enable the main character Marie to view herself, thereby also allowing the audience to see her from within.

The mirrors replicate Marie's feelings of emptiness and her striving to discover the cause of this emptiness, but they also place the audience in a situation where they can see through her eyes and experience her character. Bergman the director is a link between the actor and the audience.

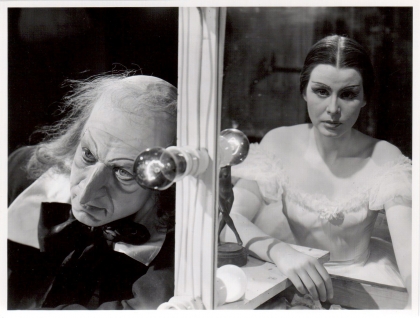

In the best-known mirror scene in Summer Interlude, the ballerina Marie is sitting taking off her makeup. Despite her tiredness she scrutinizes herself carefully. Her ballet-master then enters the dressing room. A fairly typical device of the 40s and 50s in aesthetic terms was to allow mirrors to assume a place in the composition such that the observer can hardly distinguish between reflections and the actual person. It was a recurrent feature of American film noir, one of the most famous examples being the final scene of Orson Welles' The Lady from Shanghai (1947). Bergman's variant of the device is just as effective as Welles', albeit not as obvious. When the ballet-master and Marie start to speak, we first see him from behind in the foreground, his face visible in the mirror. Marie is sitting in the background of the shot. One cut later they have changed places: now Marie is in front of the mirror in an exact replication of the previous image.

These intricate mirror effects are fascinating in their own right, but it is the ongoing dialogue between Marie and the ballet-master that cements the device. Marie complains that she feels as if her costume has been welded onto her: she finds it hard to distinguish between her true self and her professional performances "Do you really think I don't understand", the ballet-master replies: "You daren't remove your make-up and you daren't be made up." The mirror images, which the characters move in and out of, become a metaphor for the various states of the self which may be either true or illusory. It is hard to say which state the mirror image presents. The ballet-master's lines also look forward to Persona, in which the mirror theme is fundamental, but in which the mirror itself is represented in a more subtle way, often as the film camera itself. Early on in the film the doctor says to Elisabeth: "Don't you think I understand? The hopeless dream of being, not seeming, but being."

In one of Bergman's last films, After the Rehearsal, Rachel, the ageing alcoholic actress is sitting in the theatre in front of a rudimentary mirror in which her reflection is very murky indeed. Her reaction is an almost direct repeat of Jenny's lines to her reflection in Crisis: "Oh, my face ... God, my God!" From Bergman's first film to one of his absolute last, the mirror is a device in which people – irrespective of what is reflected – see themselves in more ways than one.

Bergman's characters often find themselves in such states, between seeming and being, made-up or not, and the mirror becomes (as it does for Alice in Wonderland) a portal between fantasy and reality. For a director so concerned with the question of who he "really" is, and who others "really" are, the obscuring and illuminating reflection of the mirror becomes the complete picture.

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives

- Marianne Höök, Ingmar Bergman (Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1962).

- Maaret Koskinen, Spel och speglingar: En studie i Ingmar Bergmans filmiska estetik (Stockholms universitet, 1993).

- Leif Zern, Se Bergman (Stockholm: Norstedts, 1993).