Still among the living, Max von Sydow had received the most extraordinary accolades –‘the world’s greatest’ and such – and now, upon his death, these are repeated and new ones keep coming in. I will, then, be brief, but let me start by saying that Max von Sydow has earned all the praise he got and keep on getting. He was a unique actor who to all his characters brought integrity, presence and dignity, whether his roles deserved it or not. After all, he made well over a hundred and fifty films; not all of them unforgettable, though von Sydow’s performances almost always were.

Much has been said about his collaborations with Jan Troell, William Friedkin, Woody Allen, Lars von Trier, Steven Spielberg and many more – here, I would like to say something about his significance for the cinema of Ingmar Bergman, in which von Sydow had his breakthrough.

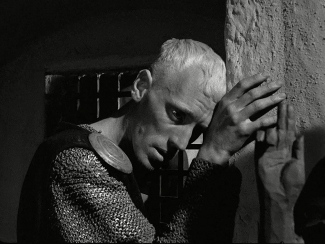

Not only cinema, by the way. Bergman and von Sydow started working together at the Malmö City Theatre in the mid 1950s, and their special relationship was shaped for and on the stage. When someone once told Bergman how great Max von Sydow was in his films, he replied: ‘Well, then you should see him on stage!’ The colossal production of Henrik Ibsen’s allegedly ‘unperformable’ Peer Gynt 1957, directed by Bergman and with von Sydow in the title role (on stage for five hours!), ranks among the greatest moments in the history of Swedish theatre. The very same year, he performed in his first two Bergman films, and these two performances alone demonstrate the remarkable range of Max von Sydow’s acting skills. The small role as a cheerful petrol station manager in Wild Strawberries grew in von Sydow’s performance to something great – the short screen time he has could alone have suffice for a complete work of art. And, incredibly enough, in the same 1957, Max von Sydow played the leading role which defined both his and Bergman’s career: Antonius Block in The Seventh Seal. The tormented knight, torn by doubt and self-loathing, struck a disharmonious chord upon which his later roles would be amazing variations.

There are two kinds of ‘Bergman men’. One is the ridicule misanthrope who tries to disguise his shortcomings behind an affected self-irony. This type is performed, often with comedic effect, by the likes of Gunnar Björnstrand or Erland Josephson. The other Bergman man is the genuinely depressed, lacking even the means to shield himself from the world by a mask. The melancholic Henrik Vogler in The Magician, the grief-struck Mr. Töre in The Virgin Spring, the suicidal Jonas Persson in Winter Light, the miserable Jan Rosenberg in Shame or the depressed Andreas Winckelmann in The Passion of Anna … No one – no one! – could play these roles apart from Max von Sydow.

With his demise disappears one of the last links to a cinema and a time so unlike ours, and yet so similar. For Antonius Block it was the plague, for Jonas Persson the nuclear bomb. For us, it may be something else, but we share the basic fear of what will happen to us, to our children, to our planet. No one – no one – could like Max von Sydow embody this fear and in doing so, offer some paradoxical solace. Now he is dead.

Jan Holmberg, CEO at the Ingmar Bergman Foundation