Ingmar Bergman the filmmaker

One of the most noteworthy filmmakers the world over.

The history of the cinema has seen directors whose works have been more "original" or "groundbreaking" (such as Eisenstein, Ozu or Godard). And there are plenty of directors who have made as many, if not more films (Griffith, Hitchcock or Chabrol). Yet the question remains: is there anyone who so epitomises the concept of the auteur – a filmmaker with full control over his medium, whose work has a clear and inimitable signature – as Ingmar Bergman?

One of the reasons one immediately recognises a Bergman film is that he is one of those rare filmmakers who has created his own cinematic world. (This is also the reason that we have a section on this website under the heading Universe.) Through recurring environments, themes, characters, stylistic devices, actors and film crews, Bergman has created his own kind of film, almost a genre in itself. If Alfred Hitchcock is the epitome of the psychological thriller (despite the fact that he also made films in other genres), Bergman has become the hallmark for the existential/philosophical relationship drama (although he, too, has made other kinds of films).

Without underestimating the impact of Ingmar Bergman's own work, his standing has also been influenced by a number of external factors. He wrote his first screenplay at the end of the Second World War, and started to make his own films during the post war years. In terms of film history, this was a time of radical change (with prevailing styles such as Italian neo-realism and film noir in the USA) which has occasionally, somewhat lightly perhaps, been referred to as a watershed between "classic" and "modern" films. In Bergman's case, however, no such division can wholly be said to exist. His films often (yet not always) use the narrative techniques of "classic" cinema with the addition of "modern" stylistic devices.

If Bergman's debut came during a period of major change in cinema history, his international breakthrough came just prior to the start of another such period. It is hardly a coincidence that it was in France in the mid 1950s that Bergman received his first genuine recognition outside Sweden. The "New Wave" was about to break, and budding directors like Jean-Luc Godard and Eric Rohmer were influential film critics who heralded Bergman, up until then relatively unknown, as the "world's foremost director". Quite simply, Bergman fitted in perfectly with the ideal they wished to promote: the auteur who uses the film camera as a writer uses his pen.

In this mould Bergman's films rapidly came to typify the concept of "art house cinema". In a period when film was once again striving for legitimacy, Bergman demonstrated that film could be something more than entertainment: it could indeed be art. As such, it is important to remember that Bergman immediately preceded the other "modern" European directors with whom he is often mentioned: Antonioni, Buñuel, Fellini, Godard and others. The fact that film studies emerged at the end of the 1960s as an academic discipline in its own right is in many respects down to Bergman, whose films of existential exploration naturally lend themselves to systematic analysis.

To a large extent, Bergman's themes laid the foundation for his fame. His Strindberg-like conviction that marriage äktenskapet is hell on earth, and his recurring doubts about God gudstvivlet were, ironically enough, and to put it crassly, not much more than a summary of the Scandinavian cultural tradition at the time, with its budding sexual freedom and its already far-reaching secularisation. Yet abroad at the time, not least in the catholic European and South American countries, or in the morally conservative United States and Eastern Europe, Bergman's films appeared revolutionary.

Neither can one totally ignore the contribution to Bergman's success of what were, for the time, quite daring depictions of nudity and "natural" sexuality. Bergman' films, with their unfathomable language, scenes of unspoilt natural beauty orörd natur and blonde women blonda kvinnor, were widely regarded as the embodiment of a Scandinavian kind of exoticism.

If one ignores the surrounding factors that contributed to the impact of Ingmar Bergman and looks instead at what makes his films unique, one can begin to discern the thematic and stylistic developments of his career. Although any attempt to compartmentalise any artist's oeuvre is of necessity a simplification, one can nonetheless divide Bergman's film production roughly into five periods. Such a division into periods requires a certain amount of omission (and in fact, the periods are often intertwined), but it does provide a snapshot of his development.

1944–1952: Working class and young lovers

Maj-Britt Nilsson and Birger Malmsten in Summer Interlude.

Photo: Louis Huch © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Focus on young lovers, especially from the working classes. Often set in the city and its surroundings (the Stockholm Archipelago). Clear influences from neo-realism, especially Roberto Rossellini. Recollection is an important stylistic device. Frequently used actors include Alf Kjellin, Birger Malmsten, Maj-Britt Nilsson and Stig Olin. Cinematographers were usually Göran Strindberg and Gunnar Fischer. Various companies lay behind the productions: Svensk Filmindustri, Sveriges Folkbiografer and Terrafilm.

Important films of this period are Torment (for which Bergman only wrote the screenplay), his debut film Crisis, Prison (his first film with his own screenplay), Summer Interlude (which according to Bergman himself was the first of his "own" films) and Summer With Monika.

1952–1955: Marriage and woman

Eva Dahlbeck and Gunnar Björnstrand in Smiles of a Summer Night.

Photo: Louis Huch © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Focus on marriage, often with the woman in the central role. Settings are often mundane, either modern cities or bourgeois environments of times past. Cinematic role models appear to be Mauritz Stiller or Ernst Lubitsch's bedroom comedies, Alfred Hitchcock's technical skills and Jean Renoir's critiques of bourgeois hypocrisy. Gunnar Fischer is almost exclusively the cinematographer of choice. Casts were recruited from his regular place of work at the time, Malmö City Theatre: Harriet Andersson, Gunnar Björnstrand, Eva Dahlbeck and Åke Grönberg. Bergman moved between two production companies: Sandrews and Svensk Filmindustri.

The most important films of the period are Waiting Women, A Lesson in Love and his first international success, Smiles of a Summer Night.

1956–1964: Metaphysics and man

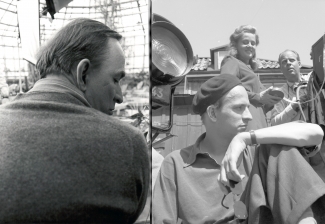

Bengt Ekerot (Death) and Bergman on set on The Seventh Seal.

Photo: Louis Huch © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Focus on angst-ridden male central characters. Settings increasingly involve barren landscapes, irrespective of whether the films are set in modern times or, as in two cases, in the Middle Ages. Despite significant differences, the religious problems presented in the films appear to be inspired by film directors Carl Theodor Dreyer and Robert Bresson. Recollection continues to play an important part, and Bergman's most important stylistic contribution to film history begins to emerge strongly: the uncompromising use of the close-up. Gunnar Fischer continues as his cinematographer until 1961, when Sven Nykvist takes over. His group of actors is now almost completely established with Malmö City Theatre continuing to supply names such as Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin and Max von Sydow. A friend from his early years, Erland Josephson begins to play minor roles. Bergman works exclusively with Svensk Filmindustri.

Almost all of Bergman's best known films are made during this period: The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries and the so-called "silence of God trilogy": Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light and The Silence. If one also adds in his extensive work in the theatre, this is the absolute creative high point of Bergman's career.

1966–1981: The role of the artist and woman

Bergman, Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann on set on Persona.

Photo: Bo Arne Vibenius © AB Svensk Filmindustri

The films are set almost exclusively on the barren Baltic Sea island of Fårö (where Bergman makes his home), and the social setting is bourgeois. The period is Bergman's most experimental, with modernist elements. Close-ups dominate the imagery in a way unparalleled elsewhere in film history. The most important actors remain, as before, Bibi Andersson, Erland Josephson and Max von Sydow, with the important introduction of Liv Ullmann. Sven Nykvist is always the cinematographer, and Svensk Filmindustri the production company until the early 1970s, when Bergman set up his own company, Cinematograph. Between 1976 and 1981 he makes films abroad (Germany, Norway), yet usually in Swedish.

The period sees the two films which many (including Bergman himself) regard as his most important of all: Persona and Cries and Whispers. Other important works include the successful television series Scenes From a Marriage and the film only recognised in recent times, the German language From the Life of the Marionettes.

1982–2003: Epilogue and autobiography

Lena Olin and Erland Josephson in After the Rehersal.

Photo: Arne Carlsson © AB Svensk Filmindustri

During Bergman's later period his films are largely concerned with a reflective summing up both of his earlier career and his own life. Previous themes such as marriage, religion and the role of the artist recur: even previous characters re-emerge. His films are made exclusively for television. Important roles are played by Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann, but also by new actors for Bergman such as Börje Ahlstedt. He also writes screenplays for other people; the subjects are his own life of those of his parents, and the directors are often people with personal connections to himself, such as his son Daniel Bergman, or his former partner Liv Ullmann.

The period's major film in all respects is Fanny and Alexander, yet After the Rehearsal, In the Presence of a Clown and Saraband also rate highly in Bergman's later filmography.

This division into periods above does have its limitations. Certain themes, for example, first appear earlier than they are mentioned above, and important films such as Sawdust and Tinsel or The Magician do not fit comfortably into the pattern. Yet as a basic overview of Bergman's film career, it also has its strengths.

A highly important director, Ingmar Bergman today seems ironically to have been virtually forgotten. His impact has been so all-pervasive, his influence so great and his films such obvious benchmarks, that his work has almost become invisible. Yet just as one occasionally has to revisit the Bible to understand something of western culture, one needs to see Bergman's films anew. For many it was a long time ago; for others it will be for the first time. Whichever it is, the films will feel familiar.

Explore the timeline that provides a handy diagram of the work of Ingmar Bergman.

Source

The Ingmar Bergman Archives.