Bergman och bildkonst

Essä av Egil Törnqvist om ett outforskat ämne.

Bergman och bildkonst

Sweden’s internationally best known ’visual artist’, Ingmar Bergman, did not express much interest in what we usually mean by visual art. Besides theatre and film, his own artistic fields, it was music that to him reigned supreme among the muses. Film, he has said, is above all rhythm. And film and music ”both affect our emotions directly, not via the intellect” (Bergman 1960: xvii-xviii).

Bergman’s seeming disinterest in visual art, the term here used in a narrow sense as referring to immobile art, may seem corroborated by his stagings. In his three productions of Hedda Gabler he disregarded Ibsen’s stage direction concerning the painting of General Gabler to be seen – like an altar piece – in Hedda’s private inner room. In his performance of O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night he ignored the picture of Shakespeare hanging above the bookcase in the Tyrone sitting room. And in his four stagings of The Ghost Sonata he refrained from Arnold Böcklin’s painting The Isle of the Dead (1880) which according to the author, Strindberg, should be projected at the end of the play. In the last case he gave two reasons for the omittance. On the one hand people are no longer familiar with this painting, on the other he himself found it ”an awful piece of art”.

But he added that as a child he was very fond of the painting, a big reproduction of which was hanging in his parental home (Törnqvist 1973: 226). It would be rash to conclude from this that Bergman as a director was indifferent to visual art.[1] When interviewed in 1968, he referred to the sculpture of Thalia in the Malmö City Theatre, where he had been working the decade before, as follows: “She’s wonderful – a huge, solid female of magnificent proportions […]. She’s indomitable, free; her whole face is one tremendous laugh. That’s how I see theatre at its best, at its most genuine” (Björkman et al. 116). When commenting on his work as a filmmaker, he chose to compare himself to those who rebuilt the cathedral of Chartres when it had burned to the ground. “Regardless of whether I am a believer or not,” he said, “I would play my part in the collective building of the cathedral” (Bergman 1960: xxii). In a program note for his film The Seventh Seal, Bergman similarly declared: “My intention has been to paint in the same way as the medieval church painter, with the same objective interest, with the same tenderness and joy” (Steene 1972:70-71). Making a film or staging a play is comparable to building a cathedral in the sense that all these activities depend on team work. The difference is that the medieval artists who built the cathedral of Chartres were anonymous and did their job “to the glory of God”, whereas the leader of the team today – the architect, the director – glorifies himself by signing his work. What strikes one is that Bergman in all these cases when describing his work as a director refers to works of visual art. Hardly a sign of indifference.

Early in 1960 Bergman was in fact planning a film about the renowned eighteenth century Swedish sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel (Sjöman 7ff.). Shortly after Bergman had directed Stravinsky’s opera The Rake’s Progress in April 1961, Vilgot Sjöman visited him in his home near Stockholm. When noticing a number of William Hogarth’s engravings on the wall – undoubtedly his series A Rake’s Progress (1735) – Bergman remarked that he had frequently looked at them when he was directing the opera (Sjöman 9). Eva Sundler Malmnäs (38ff.) has later convincingly demonstrated the impact of Hogarth’s series on Bergman’s staging of Stravinsky’s opera.

Granted that some of Bergman’s productions have been partly or incidentally inspired by visual art, to what extent can the sources of inspiration be ascribed directly to him? Since both theatre and film production depend on team work, it is likely that stage designers and property people have had their say in the matter. Thus Sundler Malmnäs (35) informs us that the Watteau painting used in Bergman’s Dramaten production of Molière’s Le Misanthrope was a suggestion by the stage designer. On the other hand, Bergman is known to have been a headstrong director and he often made a point of the fact that he was always exceedingly well prepared when starting rehearsals. Since there is little indication that he ever let himself be influenced by others in the production team, it is not likely that he did so in his use of art works. Especially not in his films, where he usually relied on his own scripts and not, as in the stage performances, on texts of others. Partly for this reason I shall in the following limit my examination to Bergman’s screen productions.

The early film Thirst (1949), carries the same title as Birgit Tengroth’s short story collection on which it is based; in either case the title has both a literal and a figurative meaning; in the United States it was trivially called Three Strange Loves. The script, written by Herbert Grevenius, skilfully combines the four stories of the collection. The main story, “The Journey with Arethusa”, deals with the train journey from Italy to Sweden undertaken by Bertil, an art historian, and his wife Rut, a former ballet dancer. Underway their problematic marriage undergoes a severe crisis, followed by a reconciliation.

Early in the film Bertil shows Rut the old coin with the head of Arethusa he has just bought in Syracuse. He tells her the underlying myth:

Remember the stream separated from the sea by a wall? Arethusa turned into that stream as she fled from the river god Alpheus. Greek mythology said the River Alpheus came all the way from Greece. It travelled under the seabed to rise and unite with the spring [Arethusa] in Siciliy. A crazy idea.

Rut objects: “Why? It could happen.” But Bertil, interpreting the myth in universal gender terms, insists: “Wishful thinking. The two sexes can never unite. A sea of tears and misunderstanding lies between them.” Here the basic theme of the film is formulated. Characteristically, the Arethusa on the coin is compared to Rut, whose name may is not altogether unlike hers:

Bertil: She looks like you.

Rut: Exactly.

Bertil: Worn out.

The opening shot of Thirst shows a black whirlpool with the film title superimposed on it. The dark restlessness of the image is strengthened by the nondiegetic music. The whirlpool represents the turmoil characterising the disharmonic relationship between Bertil and Rut.

During their journey Rut tries to jump from the train but is at the last second saved by Bertil. A little later he has a nightmare in which he murders his wife. Before they arrive in Stockholm, a subplot demonstrates how the widow Viola, after having rejected a lesbian invitation, drowns herself. At about the same time Bertil and Rut lovingly kiss each other. The moral is explicitly pronounced: however problematic, togetherness is preferable to isolation. The Arethusa coin is superimposed on Bertil’s and Rut’s embrace which dissolves into a shot of waves washing ashore, land and sea as juxtaposed opposites inevitably interconnected.

The tragicomedy Smiles of a Summer Night meant Bergman’s international breakthrough. The unanswered question of the film, Simon (135) remarks,

is whether the three general conditions to which the three smiles address themselves are to be taken as simultaneous but separate, or […] as successive phases like the seven ages of man. Are some people happy lovers, others insouciant buffoons, and still others sad, abandoned, and lost? Or are these merely three consecutive stages of the brief summer’s night and day that are human life?

Toward the end of the film Desirée, the actress with a highly symbolic first name, sings to a select group of people in the garden pavilion : “Freut euch des Lebens, weil noch das Lämpchen glüht! / Pflücket die Rose eh’ sie verblüht!” (Enjoy life as long as the little lamp is glowing! / Pick the rose before she withers!). Then there is a shot of a big dial-plate, presumably in a nearby church, showing that it is midnight. As the bells strike the midnight hour, a row of wooden figures representing different social positions appear in a circular row, one after the other. These shots underline the reminder of the brevity of life made in Desirée’s song.

As in classical comedy, the film deals with the love between several couples from different social levels. At the end we witness the love-making in a haystack by the most lowly-stationed of the four film couples: Frid, the groom, and Petra, the maid. The film concludes with a long take showing how Petra and Frid, who enjoy the simple pleasures of life, at sunrise move from their love-making in the haystack to “coffee in the kitchen”. In the final long take we get a highly universal picture of a woman, a man and a windmill, outlined against heaven and earth, the sky above and a cornfield below.

Livingston (129) interprets the windmill in Don Quixotean terms: “No one escapes from the movement of the windmill […] Bergman’s comedy, then, is a domain where the windmills of human folly hold sway, a place where men and women become puppets as the machines ruling their lives are revealed.” Closer to home than Cervantes’ novel was for Bergman a famous 14th century limewash painting by Albertus Pictor, the most famous of the Swedish church painters, in the church of Härkeberga, not far from Stockholm, a church that little Ingmar undoubtedly visited with his clerical father more than once. Variously referred to as The Wheel of Life and The Wheel of Fortune, it shows man as an inevitable victim of the age cycle, a cycle doomed to end in death. The text – “I shall reign, I reign, I have reigned, I am powerless.” – underlines the vain struggle for power and success that seems linked to the age cycle. The jester to the left, a symbol of superbia (Harlin/Noström 33), represents the fundamental human vice: pride. The wings of a windmill, forming a ‘wheel’ when in motion, is an apt symbol of the inconstancy of man’s life and of the ever-changing nature of life generally.

Albertus Pictor, Wheel of Life, Härkeberga Church, late 15th century

In his arguably best known film, the existential The Seventh Seal, set in fourteenth century Sweden at the time of the Black Death, Bergman relies for some sequences on medieval pieces of art. In an often quoted programme note for the film he points out that they concern childhood memories:

As a child I was sometimes allowed to accompany my father when he travelled about to preach in the small country churches in the vicinity of Stockholm. [...] While Father preached away in the pulpit [...], I devoted my interest to the church’s mysterious world of low arches, thick walls, the smell of eternity, the colored sunlight quivering above the strangest vegetation of medieval paintings and carved figures on ceiling and walls. There was everything that one's imagination could desire: angels, saints, dragons, prophets, devils, humans. There were very frightening animals: serpents in paradise, Balaam's ass, Jonah's whale, the eagle of the Revelation. [...] In a wood sat Death, playing chess with the Crusader. Clutching the branch of a tree was a naked man with staring eyes, while down below stood Death, sawing away to his heart's content. Across gentle hills Death led the final dance towards the dark lands.

But in the other arch the Holy Virgin was walking in a rose-garden, supporting the Child's faltering steps, and her hands were those of a peasant woman. Her face was grave and birds' wings fluttered round her head. (Steene 1972: 70f.).

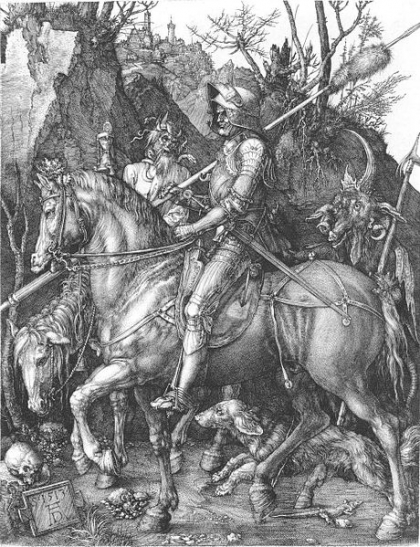

The film was originally entitled The Knight and Death (Steene 2005: 224) and it is no coincidence that this title recalls that of Albrecht Dürer’s famous copper engraving Ritter, Tod und Teufel/Knight, Death and the Devil (1513).

Albrecht Dürer, Ritter, Tod und Teufel (1513).

Wikimedia Commons.

In Dürer’s engraving we see a knight with a Christian cross on his armour riding through a narrow gorge. He is surrounded by a pig-snouted devil and the figure of Death riding a pale horse. Death holds an hourglass in his hand to remind the Knight of the shortness of his life. Both characters are threatening to the Knight, who is seemingly protected by the armour of his faith.

Early in the film we see the Knight with a huge St. George’s cross on the front of his coat of mail, the sign of the Christian crusader, as he is surprised by the sudden appearance of the figure of Death. A little later we see him and his squire as minuscule horsemen between ominous dark cliffs, as though watched by a god or by the soaring sea eagle seen in the opening of the film. Shortly after that they are confronted with the first sign of the black death: a dead man whose face has been reduced almost to a skull.

Death has come to fetch the Knight. To postpone his death the Knight suggests that he and Death play a game of chess. Outlined against sea and sky – a timeless background suggesting the universality of the situation – the two sit down on either side of the Knight’s chessboard.

Albertus Pictor, Death playing chess (c. 1485).

Foto: Håkan Svensson (Xauxa). Wikimedia Commons.

The film sequence is inspired by a limewash painting from c. 1485 by Albertus Pictor in the church of Täby outside Stockholm (Landström/Modin 53). The text of the now unreadable banderole once had the text “JAK SPELAR TIK MAT” (I checkmate you), obviously uttered by Death as he makes his final move. The painting shows us man as a young nobleman next to Death as a near-skeleton, i.e. the shape in which man will find himself immediately after death. The visualizations of two stages in man’s life confront us frontally, address us directly and thereby mirror the spectator’s will to live and his fate to die. In the film the two chess-players are seen from the side; we are clearly faced with two players struggling to beat each other; even so the struggle, as we know, is preordained: the Knight’s live face is eventually doomed to turn into a skull and become similar to that of Death.

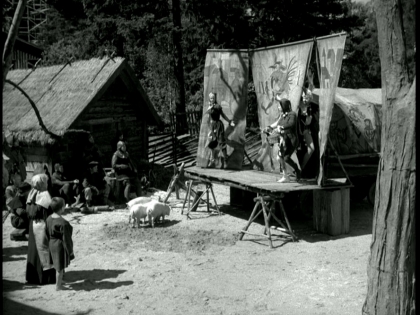

The jesters Jof, Mia and Skat perform their pantomimic farce on a simple raised stage surrounded by a rural audience which keeps mocking them. The setting has undoubtedly been inspired by the painting Peasants’ market, attributed to Pieter Balten (1540-98).

Pieter Balten (attr.), Een opvoering van de klucht 'Een cluyte van Plaeyerwater' op een Vlaamse kermis (late 16th c.).

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Part of this painting shows a farce performed on a booth stage. The husband, hidden in a baker’s basket, catches his wife flagrante delicto as she is betraying him with a priest. The erotic triangle husband-wife-lover is the same as in Bergman’s film, but in his wordless version the betrayal is indicated solely by costume, properties, gestures and mimicry.

A limewash painting by Albertus Pictor in the church of Härkeberga shows a jester in his traditional color-divided dress and horn-like cap-with-bells playing a lute. This painting has clearly served as an outward model for Jof. When playing the part of the henpecked husband Jof is dressed like the Härkeberga jester except that the bells in the flaps have been lowered to give place to two large horns.

Albertus Pictor, Jester, Härkeberga Church (late 15th c.).

Foto: Bengt A Lundberg

In the church of Tensta, not far from Uppsala, there is a limewash painting of a splendidly dressed man sitting in a tree, representing (his) life. He is counting his treasure. On the banderole he speaks of his wealth and power. Below Death, in the form of a thinly skin-covered skeleton, is sawing at the trunk of the tree (Fehrman 126). ‘Treasure’, Gado (200) points out, in Swedish is skatt; hence the name Skat for the jester who plans to sleep in a tree and suddenly discovers that it is about to be felled by Death.[2] When Skat is about to fall from his tree of life, his face is seen in close-up from below, that is, from Death’s optical point of view. His mouth is open and we expect to hear him cry out. But we hear nothing. We have to substitute the sound we only ‘see’. It is as though Skat has already taken a first step into the mute realm of the dead. The effect is similar to that in Edvard Munch’s famous engraving Skrik, sometimes rendered as Scream, sometimes as Cry. The latter rendering recalls the death of Christ: “And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying […] My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me” (Mat. 27:46). This is relevant in our context, since Skat’s mute dying is preceded several times in The Seventh Seal by Christ’s:

The slanted, from-below angle of the close-up of the man of sorrows, presumably at the moment of dying returns in that of Skat as he faces his own death in anguish. In either case no audible, only a visual cry. Ironically, Christ’s wreath of thorns has its counterpart in Skat’s jester’s hood – note the bells below his chin – which is remarkably like the Knight’s in the Härkeberga chessboard painting.

Close to the end of the film Death comes to fetch six of the characters we have earlier been familiarized with: the knight, his wife and his squire, the smith and his wife, and the young girl. In one of Bergman’s best known images, they are seen in a low angle extreme long shot treading a solemn “dance in a long row” – Jof’s words - guided by Death with his scythe. The human figures move like tiny creatures in the metaphysical borderland between heaven and earth. As silhouettes, the six have been deprived of their live individuality and transformed into dead representatives of humanity.

Ironically, this famous shot has nearly always been reproduced wrongly, showing the dancers moving downhill to the right instead of uphill to the left. In medieval drama the saved souls were always placed to the right of God. The mouth of hell and the condemned souls were placed to the left of God. From the spectator’s point of view this is reversed: heaven is to the left, hell to the right. In the film we see the six as it were dancing up into heaven. However, unlike the medieval mural paintings that have inspired it, Bergman’s dance of death is not an objective picture of what is going to happen to the six characters. It is a subjective vision by Jof expressing his hope for a happy ending on their part. Objectively, their final fate is left open.

Limewash paintings representing the dance of death were rather common in medieval Europe. But since none of them have been preserved in Swedish churches, Bergman cannot have seen them there as a child. The one closest to Sweden, preserved until recently, was the one in the church of St. Mary in Lübeck (1463), destroyed in World War II. Bergman could possibly have seen it when he was in Germany as a youngster in the early thirties. But it is more likely that he was inspired by the reproduction of part of it in Fehrman’s informative study Diktaren och döden (The Poet and Death), published just a few years before Bergman wrote the script for The Seventh Seal.

In Fehrman’s reproduction of part of the Lübeck dance of death, the “long row” is formed by alternating living and dead figures holding hands. The costumes of the living figures indicate their often high social positions. The corpse-like figures all look the same. The message is obvious. Each living character has his or her counterpart in a corpse. However different we may be in life, when we die we become all alike. The medieval dance of death has possibly emerged from the legend about the three living and the three dead, where the latter tell the former: “Quod fuimus estis, quod sumus eritis” (You are what we have been; what we are, you will become). It is likely that Bergman had this in mind when he opted for six characters (three men and three women) in his dance of death.

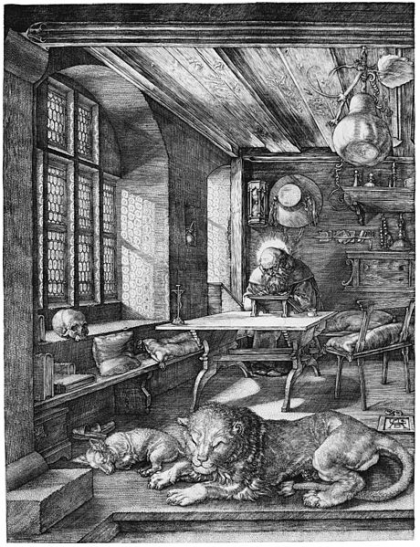

Dürer’s impact can again be sensed in the opening of Bergman’s next film, Wild Strawberries. This time it concerns the engraving St. Jerome in his Study (1514).[3] The learned scholar and translator of the vulgate bible is seen sitting behind his desk, engrossed in work. To mark his holiness his head is encircled by a halo. He is surrounded by vanitas symbols - skull and hourglass - and by two creatures: the lion whose paw he once freed from a thorn and a dog symbolizing loyalty. The leaded windows limit the amount of light let in and make the room reminiscent of a monk’s cell.

Albrecht Dürer, Der heilige Hieronymus im Gehäus (1514).

Wikimedia Commons.

In the opening of Wild Strawberries we see a another dark study with lead windows and with another learned old man engrossed in work: emeritus[4] professor Isak Borg, here too with a ‘halo’. A bitch is resting on the carpet behind him; a little later she will loyally accompany her master out of the room. On the desk is an hourglass. The ticking of a clock, another vanitas symbol, can be heard. But unlike Saint Jerome, Isak Borg is turned away from the spectator. His position reveals his misanthropic attitude to his fellow-men. Characteristically, his professorship concerns bacteriology. Suddenly the door to his study is opened and an elderly woman, his housekeeper Agda, announces that dinner is served.

At the end of the film Isak is promoted jubilee doctor at the university of Lund. This very Swedish ceremony allows those who received their doctor’s degree fifty years earlier to return to their alma mater and receive their doctor’s insignia once more. After the ceremony Isak and Agda spend the night in the house of Isak’s son Evald and his wife Marianne. When wishing Isak goodnight Agda, on her way to her own room next to his, adds: “I’ll leave the door ajar.” She seems to suggest that if Isak would feel unwell – his heart is weak – she will be nearby to help. But shortly before she says this, we see in her bedroom a painting of a reclining nude woman and in his room the small sculpture of a cock, properties which combined with her line reveal that Agda has for many years been much more than a housekeeper to Isak, that she has been his sexual partner, a hint that strangely enough seems to have escaped the critics.

Immediately before this happens Isak suggests to Agda that they start using the intimate form du to each other. Agda refuses. “A woman is jealous of her reputation”, she says, and adds: “At our age we should know how to behave.”

The irony of these lines cannot be fully understood unless we realize the true nature of the relationship between the two.

On their way to Lund Isak and his daughter-in-law Marianne visit the place where he used to spend his summer vacations as a child. He immediately looks for the wild strawberry patch of his childhood, which has given the film its title. Via the wild strawberries a flashback takes him back to the time when the house was full of life. The wild strawberry patch is Bergman’s counterpart of the biblical apple tree of knowledge. In the script it says that Isak sits down “next to an old apple tree that stood alone and ate the berries, one by one” (1960:182).

The small apple tree bears a striking similarity to the one in Edvard Munch’s painting Adam and Eve (1908). Like Munch’s couple, Bergman’s appear close to the apple tree (and the strawberry patch), dressed in early 20th century fashion. Munch’s Eve is eating the fatal apple and obviously telling her Adam how delicious it is. Between themselves the black tree worms itself, serpentlike. It is the moment of the Fall, the moment when our original forefathers lost their innocent nakedness.

Bergman’s couple are named Sigfrid and Sara. Sara is secretly engaged to Isak. Sigfrid is his brother. When Sara willingly lets herself be kissed by Sigfrid, she drops the basket in which she has gathered the wild strawberries and discovers that she has got a stain on her apron, significantly where the fig leaf belongs. The Fall in the film consists on an individual level in Sara’s betrayal of Isak. Beyond this, it signifies the Fall of man, a repetition of the Original Sin. It is an image of paradise – the innocence of childhood – lost, both with regard to the individual and to mankind.

Isak has never witnessed the betrayal. But he has undoubtedly heard about it from the gossipy twins. And he may well have imagined the way it was done. In that respect the situation recalls another Munch painting, Jealousy (1895).

Edvard Munch, Jealousy (1895).

This painting refers to the affair the artist had with the Polish writer Stanislaw Przybyszewski’s wife Dagny Juel, represented in the background as a semi-nude Eve tempting Adam alias Munch with the apple. “The deviation from biblical nudity serves, of course, to restate the old theme in a contemporary context” (Messer 82). The jealous head in the foreground corresponds well with Isak’s jealous reliving of his fiancée’s betrayal of him with his brother.

During his journey to Lund Isak makes a short visit to his old mother. In the drawing room is a big painting of an old man with a long beard sitting at his desk (as we have earlier seen Isak sitting at his).[5] It presumably represents Isak’s deceased father. If so, the picture adds to the line of male Borgs represented by Isak and his son Evald.

The significance of the grouping appears later when Marianne, referring to the three Borg generations she has now become familiar with, comments: “there is only coldness and death, and death and loneliness, all the way.” If the bearded old gentleman on the painting resembles a child’s imaginary picture of God, it is no coincidence. Shortly before the visit to his mother Isak has quoted from hymn 564: “Where is the Friend, whom everywhere I seek”. In the film’s last flashback Isak is desperately looking for his absent father. Finally he finds him in a vision that is at once a nostalgic remembrance of a childhood situation and a hopeful wish for reunion in life hereafter. To the child the earthly father plays the same role as the heavenly father does to the grown-up. The painting of the old bearded man on the wall is a visualization of this doubleness of the father figure on Isak’s part.

A more emphatic use of a work of art is found in the innovative The Silence. Two sisters, Anna and Ester, and Anna’s ten-year old son Johan are on their way home to Sweden from a visit abroad. They make a brief stopover in an unnamed country whose language is unintelligible both to them and to us. In their hotel there is a huge painting: Rubens’ Deianeira Abducted by Nessus:

The motif is an episode in Graeco-Roman mythology. Hercules and Deianeira, recently married, suddenly arrived to a river. The centaur Nessus offered to ferry them across. While midstream with Deianeira, Nessus tried to rape her. But Hercules answered her screams by shooting an arrow in Nessus’ heart. In Rubens’ painting we do not see Deineira screaming and we seem to witness a seduction rather than an abduction.

Like most cinema viewers, Johan would be ignorant of what the painting mythologically represents. What he sees is, in the words of the script (Bergman 1970:114f.),

a fat, entirely naked lady, fighting with a man in hairy fur pants and with hooves in lieu of feet. The lady is very pink, and the dark brown man is covered with hair. On closer inspection the lady, to judge from her stupid smile, doesn’t seem altogether displeased by his attentions.

Johan has earlier told Ester that he is afraid of horses. Significantly, Nessus’ left side with the wound in his heart is shaded, hardly visible, in Bergman’s shots. It falls outside Johan’s scope of attention or, alternatively, hides his oedipal wish to kill the horse-man. “The naked, fleshy woman and the fearsome horse-man heighten the hypersensitive Johan’s anxieties and oedipal fears, even as the arrow represents his hostility” (Cohen 214). More closely, the painting foreshadows the doggy style intercourse between Johan’s mother Anna and her waiter pickup. Characteristically, Johan eavesdrops as the two move into an empty room in the hotel; once they are inside, he puts his ear to the door. As in art, so in life. But unlike Hercules, little Johan may not understand what is happening and if he does, he lacks the power to revenge himself.

There are no less than four shots of the painting. In the first one which is a long shot we see Johan from behind, a pistol in his hand (cf. Hercules’ bow), watching the painting. Whereas he sees it in its entirety, a column in the foreground prevents us from seeing the Deianeira part of it; it is in other words at this point still unclear to us what the painting actually represents.[6] The second shot, which is a close-up from Johan’s point of view, focuses on the sexual relationship between Deinaeira, now visible also to us, and the horse-man, whose subhumanness agrees with Johan’s oedipal imagination. In the third shot the painting is for the first time seen in its entirety also by us. In the fourth and final shot we have moved slightly closer to the painting and watch it along with Johan whose head is seen in front.

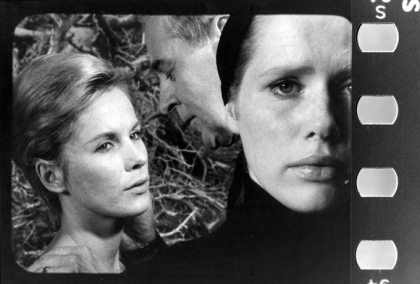

Persona deals with the relationship between Elisabet Vogler, an actress, and Alma, a nurse. Elisabet experiences language as false. Suddenly, in the middle of a stage performance, she chooses to turn mute. Her doctor asks Alma, to help Elisabet overcome her muteness. When it appears that Elisabet has rejected her child, Alma who has undergone an abortion, begins to identify herself with her patient. She becomes her confidante with her. When Elisabet betrays her confidentiality, Alma takes revenge by dreaming of herself in a liaison with Elisabet’s husband.

“During Alma’s conversation with Mr. Vogler,” Cohen (243) points out, “Elizabet’s back – she is facing us – is to the couple, but because this is a dream, Alma can see her face just as we do; in fact, we are made conduits of the dream.” The composition, he adds (245), seems to have been inspired by Munch’s Jealousy, earlier reproduced here.

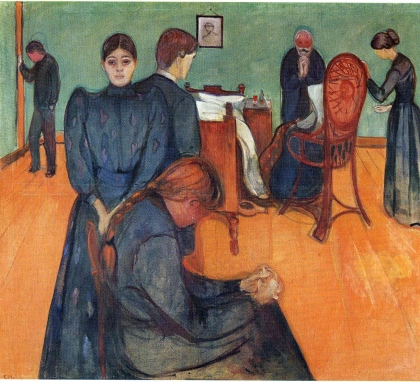

Cries and Whispers describes the suffering and death of an unmarried young woman, Agnes, probably in her early thirties. In a few shots we see her sisters Karin and Maria and her housemaid Anna waiting in the room next to her death-bed. The arrangement is simlar to that in Edvard Munch’s Death in the Sick Room (1893); even the period agrees with that in the film.

Edvard Munch, Death in the sickroom (1893).

© Munchmuseet, Oslo.

Once dead, Agnes is laid out for a final leave-taking. Here another Munch painting, By the Death Bed (1895), seems to have inspired Bergman.[7]

Edvard Munch, By the Deathbed (1893).

© Munchmuseet, Oslo.

Unlike Karin and Maria who shie away from the dead Agnes, Anna tends her the way a caring mother would.

In Michelangelo’s famous Pietà (1498-99), in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, Virgin Mary is miraculously young. There are different interpretations why this is so. One is that her youth symbolizes her purity. Another is that it indicates that she is not only holding the recently dead Jesus in her arms but also the recently born Jesus. Her youthful appearance and serene facial expression, coupled with the position of the arms may suggest that she is seeing her child, while the viewer is seeing the crucified Christ.

Michelangelo, Pietà (1498–99).

Wikimedia Commons.

Since Anna as a single mother has earlier lost a dearly loved child, her caring for Agnes is clearly substitutive. Since Agnes, similarly, has lost a dearly loved mother, Anna is as clearly substitutive to her. In this sense the two are mother and child, an impression strengthened by their biblical names, Anna being the mother of Mary and Agnes’ name (from Greek ἁγνῶς , chaste) reminding us of Agnus Dei, God’s lamb.[8] There are various signs in the film that Agnes’ suffering and death are modelled on that of Christ (Törnqvist 1995:153). Both in its mother-child connotations and its religious overtones Bergman’s pietià recalls the numerous lamentations of the dead Christ, of which Michelangelo’s is the most famous.

The TV opera The Magic Flute, based on Schikaneder’s libretto and Mozart’s music, was shot in a studio modelled on the 18th century Drottningholm theatre. The drop curtain of the theatre, attributed to the court painter Johann Pasch, shows Minerva, sitting on a cloud. A plumed helmet on her head, she holds in one hand the festooned monogram of Queen Lovisa Ulrika, founder of the theatre, in the other a spear.

Minerva’s plumed helmet is not unlike the helmet worn by the militant Queen of the Night at the end of the opera. And the way in which the goddess holds her spear is echoed in the way the three ladies, who serve the Queen, hold theirs when killing the dragon. By relating the curtain in this manner to what is behind it, Bergman makes us experience it, not as a separating but as a unifying fourth wall providing a premonition of what is to come.

Sundler Malmnäs (41-45) sees similarities between the temple priest scene in Bergman’s Magic Flute and Rembrandt’s huge painting The Conspiracy of the Batavians under Claudius Civilis (1661-62) in the National Museum in Stockholm.

There are indeed striking similarities in the grouping of the characters around the table and in the chiaroscuro lighting. But thematically the pagan chieftain and his conspirators have little in common with Bergman’s benevolent ruler Sarastro and his brethren. In this respect their gathering is more resemblant of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting The Last Supper (1498) that shows the last meal shared by Jesus and his twelve disciples.

The painting catches the commotion after Jesus has said “one of you shall betray me” (Mat. 26:21). It is no coincidence that a tall Sarastro, like Jesus in da Vinci’s fresco, is placed exactly in the middle at the table; that his hands are raised to prayer; that he is surrounded by six brethren to the left and six to the right; and that the halbards of the three guards behind them bring to mind the three crosses of Golgotha – all resemblances that give Bergman’s Sarastro the status of a Christ figure.

In Johan Tobias Sergel’s marble group Mars and Venus (1770) the wounded Venus, goddess of love in Roman mythology, is rescued by her lover Mars, the god of war. The goddess sinks upon the knee of Mars who, with a gaze of defiance and concern, raises his helmeted head to the world around him as he clasps the falling Venus in his arms. The sculpture expresses anxiety and pain but with an erotic undertone.

In the TV series Face to Face (1976), the psychiatrist Jenny Isaksson discovers that she cannot relate emotionally to other people, that she is a psychological cripple. Her grandfather is decrepit and totally dependent on the care of his wife, Jenny’s grandmother. At one point Jenny is seen standing behind a curtain watching the two communicating silently.

The shot reveals how the traditional relationship between the sexes, visualized in the replica of Sergel’s marble group in the background, is reversed by the couple in front. Positioned as two equals, it is here the woman who represents the stronger sex. It is she who consoles the weak, sobbing man. Unseen by them Jenny watches the two from behind a hanging. What she witnesses is a love for the other which has been lacking in herself but which eventually gives her faith in life and courage to go on living.

The first part of the tv-series Fanny and Alexander (1982) is set in Helena Ekdahl’s huge and sumptuous apartment. In the drawing room there is a sculpture of a semi-nude woman. Suddenly, as sunlight enters the room, the sculpture miraculously raises her left arm. The subjective shot shows that the woman has come alive in Alexander’s imagination.

To the right, behind an indoor palm tree, in an even more subjective shot, a skeleton with a scythe is slinking silently in the direction of the woman sculpture[9]; unwittingly she is being threatened by Death. Already in these early shots we enter Alexander’s mind, his awareness that life is constantly being threatened by death. We are not far from the confrontation between the Knight and Death in The Seventh Seal.

The Ekdahl apartment bears witness to the family’s sensual enjoyment of life. When Emilie, after her husband’s death, is married to bishop Vergérus, she and her children are confronted with the opposite view of life, life as a preparation for life hereafter. The contrast is expressed in that between the exuberant Ekdahl interior and the one of the ascetic Vergérus.

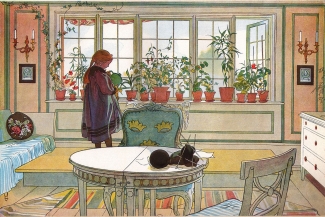

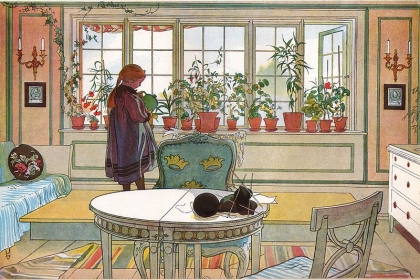

Act III of the series is set in the drawing room of the Ekdahl summer home. The light interior reflects the family’s esthetic refinement and positive attitude to life. Presumably located in the province of Dalecarlia where little Ingmar spent his vacations in the summer home of his maternal family, the interior strikingly resembles Carl Larsson’s water-color The Flower Window (1894), one of the pictures in the artist’s book A Home, depicting his own home in Sundborn.

Carl Larsson, Blomsterfönstret (1894).

Wikimedia Commons.

The book was published in 1899, a date that agrees well with the time in which Fanny and Alexander is set: 1907. Carl Larsson is still enormously popular both in and outside Sweden as the painter of idyllic family life.

The preceding examination has dealt with some works of art in their relation to Bergman’s screen productions in two different ways: as possible inspiration for certain screen elements and as visualized parts of the productions. As visualized parts they sometimes appear already in the scripts, as in the case of the Rubens painting in The Silence. In other cases they have been added afterwards, as in the case of the Sergel group in Face to Face. Some of the screened art pieces are to be found in a public space; this goes, for example, for the medieval church paintings in The Seventh Seal. Others, such as the paintings in the Ekdahl home in Fanny and Alexander belong to the private space. A third aspect has to do with the relationship between the visible works of art and the characters in the productions. As we have seen, the Arethusa coin in Thirst is related both to Bertil and Rut, whereas the Rubens’ painting in The Silence is connected only with Johan and the woman scultpure in Fanny and Alexander only to Alexander.

A more interesting aspect – and the main purpose of this essay – concerns the affinity between certain works of art and particular sequences of the screen productions. Whenever such an affinity seems convincing, the result is a broadening and enrichment of the viewer’s experience of such sequences.

Egil Törnqvist är professor emeritus vid institutionen för skandinavistik på Universiteit van Amsterdam. Han är författare till ett dussintal böcker om i synnerhet Ingmar Bergman och August Strindberg, senast den tvåspråkiga Drama as Text and Performance: Strindberg's and Bergman's Miss Julie / Drama som text och föreställning: Strindbergs Fröken Julie och Bergmans (Amsterdam: Pallas Publications, 2012).

[1] Peter Cowie’s claim that Bergman at the end of the 1930s chose “literature and history of art” for his study at Stockholm University is, however, probably incorrect with respect to the latter subject. Cowie provides no source for this claim. And we lack further evidence that Bergman’s study concerned anything but literature.

[2] The name is also reminiscent of Swedish skata (magpie), the bird notorious for its thievishness.

[3] Mats Rhodin (11f.) has interestingly analysed the similarity between this engraving and the picture of Isak Borg in his study.

[4] There is a striking similarity in Swedish between the words emeritus and eremit (hermit). As Rhodin (11) notes, both words apply to Borg, whose surname, meaning ‘fortress’ indicates his egocentric, self-protective nature.

[5] The painting, from 1923 by David Wallin, portrays the literary historian Henrik Schück (1855-1947). In the fall of 1940 Bergman attended the Strindberg lectures of prof. Martin Lamm, one of Schück’s pupils, another generation triad.

[6] Koskinen (120) gives a somewhat erroneous description of the painting squence when she writes: “The first time [Johan sees it], the focus is on the center of the painting […]. The second time, the painting is seen in its entirety […].“

[7] I am indebted to Cohen (254) for the reference to these two Munch paintings. A rehearsal shot from the film reproduced by him (255) shows dead Agnes in exactly the same position as the dead person in Munch’s painting.

[8] Indra’s Daughter, the Christ figure in Strindberg’s Dream Play, is named Agnes once she takes human form. Bergman produced this play four times.

[9] In the much shorter film version of Fanny and Alexander this bit is alas omitted.