The myth, the man

Ingmar Bergman's life and work are hard to differentiate, and that's putting it mildly.

'More or less consciously I have divided myself into three characters.'Ingmar Bergman on The Ritual (1969)

The myth, the man

The first substantial article on Ingmar Bergman appeared in the newspaper Göteborgs-Tidningen on 19 September 1943 under the heading "25 year-old director makes a name for himself in Stockholm". The heading was referring to his efforts in the world of student theatre. He was yet to make his film debut, yet he did so the following year as the screenwriter for Torment. In the same year he was also appointed by the Helsingborg City Theatre as Sweden's youngest ever theatre manager.

Within a few years he had directed a number of films and an even greater number of stage plays, and had also written and published some original plays and short stories. An image of Bergman quickly grew as a talented young artist with demonic tendencies and an insufferable temperament. He was also reputed to have an unhealthy penchant for sexual matters and psychological problems, and for the dark forces that drive them. In every way Ingmar Bergman fitted the picture of 'the young genius' that people either loved, hated, or loved to hate.

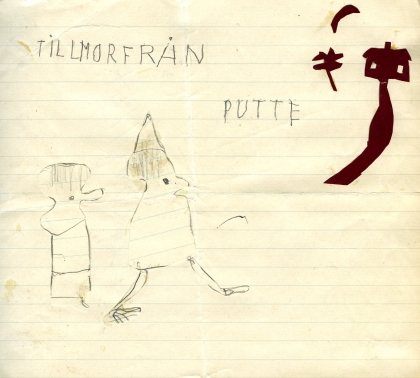

"To Mother from Putte". Mixed media. Ingmar Bergman, c:a 1923.

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

The second of three children, Ernst Ingmar Bergman was born on 14 July 1918. His father was Erik Bergman, a clergyman. His mother was Karin Bergman, née Åkerblom, a qualified nurse. In many contexts Bergman has spoken of his upbringing as strict, with occasional moments of tenderness, intimacy and love.

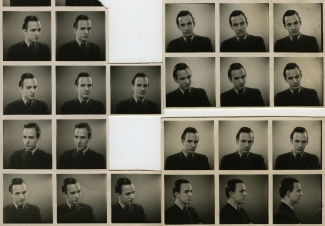

Erik and Karin Bergman, c:a 1918.

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

Nonetheless, his childhood has clearly meant much to him, not least in his professional life. In addition to his beloved mother he has also named his maternal grandmother, his nanny Mait and the family cook Malla as powerful influences on his early life. By his own admission, Bergman was "fantasy-obsessed", often escaping into a world of his own creation from a family environment which, although free from financial worries, was overridingly austere. The meeting between these two worlds was not always trouble-free:

So, when reality was no longer sufficient, I began to fantasize, entertain my playmates with tremendous stories about my secret adventures. They were embarrassing lies that hopelessly failed against the level-headed scepticism of the world. I finally withdrew and kept my dream world to myself. A young child wanting human contact and obsessed by his imagination had been hurt and transformed into a cunning and suspicious daydreamer. (The Snakeskin)

There is a general tendency in studies of individual artists to analyse their lives in detail to find keys to their works. Few artists have had to put up with such a thorough examination of their childhood as Ingmar Bergman, yet the burden is largely of his own making. In countless interviews, many of his artistic creations and not least in his autobiography The Magic Lantern, Bergman has revisited his childhood and its impact his work.

This website has no intention of adding to the many extensive surveys of Bergman's childhood, of how toys such as a puppet theatre or a magic lantern determined his future choice of profession. Nor, for that matter, of providing detailed accounts of his many love affairs, his six wives or his nine children. On the other hand, one must at least be aware of certain things in order to gain an understanding of his work, such as the parallel worlds he invented for himself as a child, or the intense focus on him as a person brought about by amazing success relatively early in his life. This scrutiny must at times have bewildered him. And yet in the case of Ingmar Bergman, scrutiny of the relationship between his life and his work, however sceptical one might be of biographical analysis or the cult of genius, is unavoidable, integral and highly interesting.

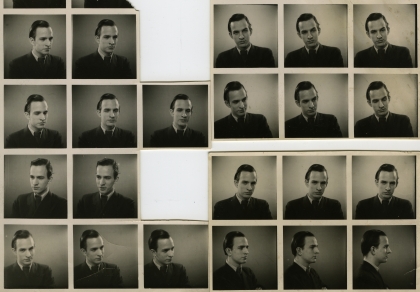

Who was Ingmar Bergman, really?

© Stiftelsen Ingmar Bergman

In 1946 Bergman left the Helsingborg City Theatre, publishing in the programme for his production of Requiem, a "Farewell Interview" with himself. This was the first time he used this type of literary device, one to which he would return many times: either, as here, staging an interview with himself, or by writing (often critical) articles about himself under a pseudonym. A literary highpoint in Bergman's efforts in this vein is a curious piece of writing, Ingmar's self-portrait, from 1957.

This short piece relates an anecdote from the Cannes Film Festival, where Bergman was staying, and where his Smiles of a Summer Night picked up an award. One evening a Russian artist arrived at Bergman's hotel room asking if he would agree to sit for a portrait. "He positioned me by the window, half turned away. To the right there was a large free-standing mirror." Clearly uncomfortable with the role reversal of being directed, Bergman nonetheless posed politely. When he saw the finished result he discovered that the artist had portrayed him in two versions, "one direct, so to speak, the other in the mirror." What is more, the two likenesses appeared to differ in age: One was like a little boy, whilst the mirror showed the image of an old man, "a ghost with a tired expression". Bergman's reaction was to produce a third image, complete with an egg-shaped head, long nose and protruding ears. Now there were three portraits of Bergman, all "uncomfortable truths": the boy, the old man and the figure he had drawn himself.

Three portraits of Bergman.

Illustration: André Wachholz

Suddenly the old man in the mirror started talking; naturally it was a trifle surprising, but at a festival, anything can happen. The old man said: Admit that you were flattered when the artist wanted to draw you. You love thinking about yourself, talking about yourself, looking at yourself in the mirror. You're a vain bastard.

The boy replied that he whilst did indeed have his moments, his desire to please his audience should not be mistaken for vanity. After a brief argument between the two of them, the third figure, the one that Bergman had drawn, began to try to mediate between them. The argument continued until the three different Bergmans appeared to change places and take on each other's "masks" (as he puts it). It was no longer possible to follow the discussion. He tore up the pictures and the voices fell silent. Bergman concludes that "self-portraiture is something one should never get involved in, since it is wrong to lie even though one endeavours to tell the truth."

Although one should be wary of reading too much into this minor piece, it does, for all its absurd comedy, seem to provide a key to a fuller understanding of Ingmar Bergman. He presents us with an obviously made-up story about an artist portraying another artist with the result that the creation assumes a life of its own. A more pertinent portrayal of the cult of genius, as suffered by many artists, especially Bergman himself, is hard to imagine. Worthy of note too is that one of the artists in the story borrows stylistically from the other. The presentation of a character and his or her mirror image is typically Bergmanesque. And the situation in which various characters glide and out of each other's roles is also something that we recognise from later films like Persona.

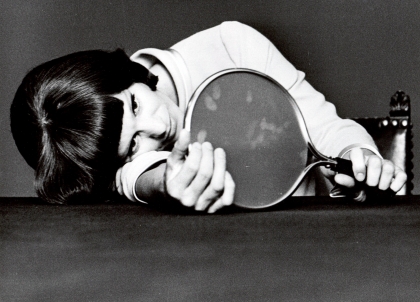

Ingrid Thulin in The Ritual (1969).

Furthermore, the fact that he divides himself into a several versions is a stylistic device which might possibly be explained by Bergman's lifelong habit of creating fantasy worlds, or perhaps as a reaction to the manifold descriptions of himself that he must have read and mulled over by the time he wrote this piece. Irrespective of such musings, we recognise the same device in films such as Cries and Whispers and Fanny and Alexander, where various characters are aspects of one and the same ego.

Ingmar's self-portrait shows us Bergman commenting on his public position, his status and the relationship between his life and work in a way that is both complex and subtle. The large canon of Bergman research (some of which he himself has conducted) has often focused on biographical details, analysing his films, stage productions and writings as the products of his life. Yet perhaps one might also take the opposite view: that Ingmar Bergman's "life" – as we know it – might be regarded as an extension of his work.

As previously stated, "Ingmar's self portrait" concludes with a warning that one should never become involved with self-portraiture since it is wrong to lie. Some thirty years later he decided to go against his own advice. And yet when setting about his autobiography he was still tentative about the task at hand. In a short, undated and unpublished draft for The Magic Lantern he wrote:

I'm planning, you see, to try to confine myself to the truth. That's hard for an old, inveterate fantasy martyr and [illegible] liar who has never hesitated to give truth the form he felt the occasion demanded.

Bergman certainly appears to have a healthy scepticism towards his capacity for the truth. This is also a recurrent theme in his films, with Elisabet Vogler's radical decision in Persona as the most obvious example: rather than lie she opts to remain completely silent. For Bergman, the fear of falsehood is rooted in a mistrust of language itself. But the question as to what constitutes truth or falsehood is seldom simple, especially when it comes to the distinguishing between Bergman's life and work: what we presume to be true in relation to what is fictitious.

Barbro Hiort af Ornäs and Bibi Andersson in The Touch (1971).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

The Bergman expert Maaret Koskinen has brilliantly demonstrated how one scene from end of The Magic Lantern, in which Bergman bids farewell to his dead mother, reveals interesting similarities with a scene in The Touch. The film appeared after his mother's death, so one's immediate reaction might be to regard the event as the trigger for the scene. Yet as Koskinen concludes:

Here it does not appear to be simply the case that a starkly real event, so to speak (or rather the memory of it which, strictly speaking and at any given moment, is all we have to go on) has preceded and in any linear sense provided the material for a film scene. Furthermore, it might well be the case that the writer of the autobiography has allowed a fictitious film scene to intervene in, or 'contaminate' (the memory of) an event that took place in real life.

Any close examination of Bergman's "pure" works of fiction and what one might term his "autobiographical projects" (not only The Magic Lantern and Images - My Life in Film, but also works like Fanny and Alexander, The Best Intentions, Faithless and countless interviews) quickly reveals that a simple division between fact and fantasy is not possible. Just like everyone else – perhaps more so – Bergman is hard to pin down, multifaceted and complex, as evinced by his tendency to present various versions of himself and his characters, and his apparently compulsive habit of regarding the self as a divided entity.

Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann in Persona (1966).

© AB Svensk Filmindustri

In an interview in the 1960s Bergman was asked if he cared about his fame and all the things that were written about him, to which he replied: "Not especially. Sometimes articles are sent to me directly, and then I read them, but I never seek them out. And it always feels as if they're about someone else, a relative perhaps." Long before he donated his private archives to The Ingmar Bergman Foundation he would employ the same evasive tactics. If someone asked him whether he had kept any of his workbooks or other material (which he had, in fact), he would either answer that they had disappeared, or that "some distant relative" had taken charge of them. Once again one is reminded of his story of the portraits and the mirrors: different personae, same person.

In Summer Interlude Marie's ballet-master, himself in full make-up, speaks of how it feels neither to dare to remove one's make-up nor to be made up. In Hour of the Wolf, Baron von Merkens remarks to Johan, having made him up to be unrecognisable: "There. Now you are yourself, yet not yourself. The ideal state for a romantic encounter." In his production of The Ghost Sonata Bergman allowed Hummel, in Maaret Koskinen's words, "to brutally unmask the Officer: forcing him to remove his wig, his false teeth, his moustache and the truss he wears under his uniform, and then to crawl around putting his social masks back on in full view of the audience." All throughout Bergman's works, in his films, plays and writings, he returns to the subject of masks, in which every human being's "self" is prey to the forces that control the eternal to and fro between several possible "selves".

Though highly self-revealing in his films and writings, Ingmar Bergman was a reclusive man who seldom appeared in public. This fascinating combination made him into a person about whom many people feel they knew a great deal, yet who nonetheless remained a mystery. The question as to who Bergman actually was can only be conclusively answered as he answered it throughout his life: he was one and many at the same time.

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives

- Ingmar Bergman, Images

- Ingmar Bergman, Laterna magica

- Ingmar Bergman, Ingmars självporträtt

- Stig Björkman, Torsten Manns och Jonas Sima, Bergman on Bergman (Stockholm: P.A. Norstedts & Söners Förlag, 1970).

- Jan Holmberg, Ingmar Bergman as 'Ingmar Bergman', Film International (nr. 3, 2005).

- Maaret Koskinen, Ingmar Bergman: Allting föreställer, ingenting är - filmen och teatern - en tvärestetisk studie (Nora: Nya Doxa, 2001).