Fanny and Alexander

When Fanny and Alexander's kind-hearted father dies, their mother marries the cruel Bishop Vergérus.

"Fanny and Alexander is like a summing up of my entire life as a filmmaker."Ingmar Bergman

About the film

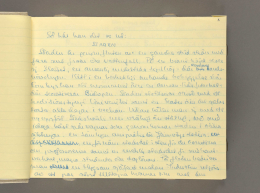

In the wake of the notorious tax imbroglio, Bergman lived in Munich between 1976 and 1982. Fanny and Alexander was to mark his return to Sweden. In 1978 he wrote in his workbook: 'There is no longer any distinction between my anxiety and the reality that causes it. And yet I thing I know what kind of film I want to make next. It is far different from anything I have ever done.'

The difference partly consisted in the fact that he was now about to portray life in a more idyllic way. It was his friend Kjell Grede (married at the time to Bibi Andersson) who had once asked Bergman why he always made such gloomy films when in fact he himself was a lover of life. Bergman's feelings at this juncture were in something approaching a state of flux, because when he finally made his mind up to display his lighter side, he was actually finding life rather difficult to bear. Writing in Images: My Life in Film:

'It was the same with Smiles of a Summer Night, which also burst forth during a time of uncertainty. I think it may be because the creative juices flow faster when the soul is threatened. Sometimes such a state brings luck and insight in its wake, as in Smiles of a Summer Night, Fanny and Alexander, and in Persona. Sometimes, as in The Serpent's Egg, all goes awry.'

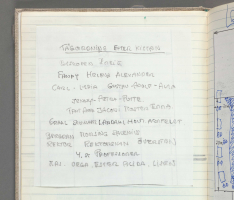

Yet when work on the screenplay got under way, Bergman's good humour returned in abundance. The tax case against him was dropped: he was acquitted on all counts. Unlike Scenes from a Marriage, for example, which was a low-budget project right from the outset, he now set to work without worrying whether his new film would be either expensive or difficult to shoot. "As a consequence, it turned out to be extremely expensive and extremely difficult!" The number of actors he initially envisaged gave a hint of what was in store. The screenplay cast list required fifty four actors (three were removed later), so that in terms of scale alone, Fanny and Alexander was set to become Bergman's biggest production by far. In writing the screenplay Bergman was at his most prolific: scene followed scene, and the volume of material simply grew and grew. 'I found a bore hole, and oil (or whatever it was) suddenly started gushing out

.'

As to the structure of the film, Bergman explained that certain parts are seen from Alexander's point of view, others more objectively. 'I've changed my viewpoint whenever it has suited me. There's no real objectivity in the pattern. Nor any given style. I bring together various styles, I'm not interested in that kind of thing. I'm telling a story.'

The British impresario and film producer Sir Lew Grade was the first potential source of finance for the film (he had previously provided part of the funding for Autumn Sonata). Grade gave Bergman a draft contract which stipulated that the film should be no more than two and a quarter hours long. When Bergman pointed out that it would be longer, Grade immediately pulled out. Bergman was almost relieved. 'I thought it was the will of God, a hint that I shouldn't take on such an extensive project. But then along came Jörn Donner who said: 'Just make the film! I'll fix the cash!'

Donner, the head of the Swedish Film Institute, had been given the screenplay to read during a visit to Munich. He read it all the way through one night, and the next morning came up with what he would later call his 'rash promise', given on condition that the film would be made in Sweden. This was a stipulation that Bergman at first opposed on the basis that, in the wake of the closure of Film City, there was no suitable studio in Sweden. Yet he soon gave way: Donner would scarcely be able to persuade the Film Institute to underwrite production without any benefit to workers in the Swedish film industry. A few days before the film's premiere Donner felt obliged to write an article in Svenska Dagbladet to justify his decision. The funding of the film and the alleged lack of it had stirred up a new debate as to whether Bergman took the bread from the mouths of his colleagues by draining the Film Institute of money. (Ten years previously, a similar debate had surrounded Cries and Whispers.)

It is quite clear that I overstepped my authority as head of the Swedish Film Institute. My reasoning was quite simple: if the Film Institute existed to support anything, then Swedish film was the obvious candidate. Its leading artist of modern times had written a screenplay which in many respects summed up his artistic career as an auteur and filmmaker. It would be a disgrace, I thought, if that film was never made.

The financial risk was considerable, and funding the project was a complicated affair in which the Swedish Film Institute was the main producer, sharing the burden with Sandrews, Bergman's Swedish company Cinematograph, his Swiss company Personafilm, Gaumont in France and Tobis Filmkunst in Germany. The costs and risks were the principal reason why the film was released in two versions, the 5-hour TV series originally planned, and the shorter cinema version biografversionen (197 minutes) which was primarily intended for sale on the international market.

Sources of inspiration

The poor reception of From the Life of the Marionettes appears to have acted as a spur to Bergman, inspiring in him the necessary energy to carry through the biggest film project Sweden had ever witnessed. He had been on the verge of calling it a day as a filmmaker, but found himself unable to do so. 'When you're young', he observed, 'you can tell yourself that if it goes to hell, then you can always do something else. But the older you get, the more afraid you become. Afraid of not being able to live up to your own quality demands, of not coming up to the mark.' Writing in Images:

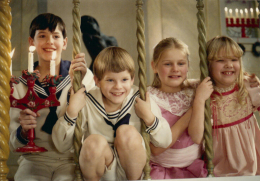

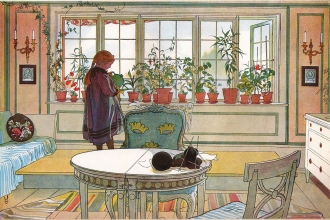

Fanny and Alexander has two "godfathers". There is [...] an illustration by E. T. A. Hoffman's stories that had haunted me time and time again, a picture from The Nutcracker. Two children are quivering close together in the twilight of Christmas Eve, waiting impatiently for the candles on the tree to be lighted and the doors to the living room to be opened. It is that scene that gave me the idea of beginning Fanny and Alexander with a Christmas celebration. The second godfather is Dickens: the bishop and his home, the Jew in his boutique of fantasies, the children as victims; the contrast between flourishing outside life and a closed world in black and white.

A third godfather, or rather father, is Bergman himself as a child. In this his most autobiographical work, he gives himself free rein with the inner and outer images of his childhood, its people and settings, and also with the young Ingmar's hopes, perceptions and imaginings.

The two poles of Fanny and Alexander, the vivacious theatre family as opposed to the strict regime of the bishop's house can be traced to Bergman's own childhood. On the one hand his early years were marked by 'good humour, plays, songs, music, poetry reading', and on the other by 'austerity, moralising, denial, rigidity, brutality'.

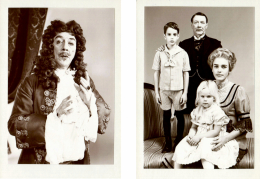

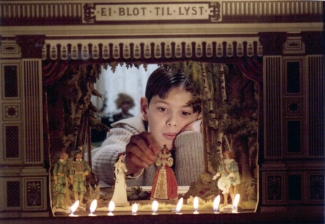

It would be an impossible task to plumb all the autobiographical details in the film. Yet the most striking of them certainly warrant a mention. The Ekdahl apartment, for example, is almost an exact copy of Bergman's grandmother's apartment in Uppsala. And the similarity of Alexander to the young Bergman, accentuated by the actor Bertil Guve's almost uncanny physical resemblance to the director as a child, is beyond doubt. His pastimes (the puppet theatre and the magic lantern) are identical with those of Bergman himself.

Many of the other characters also reflect Bergman's childhood. The grandmother and matriarch Helena Ekdahl is in essence an affectionate portrait of Bergman's own beloved grandmother. And her son Carl appears to have much in common with Bergman's own "Uncle Carl", whose eccentricities are described in particular detail in The Magic Lantern. The nanny Maj bears a more than passing resemblance to Bergman's own nanny Mait. And so on. The most objectionable character, Bishop Edvard Vergérus, shares not only the profession of Bergman's father, but also what Bergman perceived as his austerity and uncompromising nature. However, Bergman has stated that: 'there is more of me in the bishop than in Alexander, he is afflicted by his own demons.'

Bergman also enjoyed a few 'in-jokes' in the cast list. A minor character, for example, is one Mikael Bergman, described in the screenplay as 'young, promising, plays Hamlet'. Here, the director clearly appears to have sneaked in yet another alter ego. As the enfant terrible of Swedish theatre in the 1940s, Bergman was often described as 'young and promising', and at the outset of his career he was known to try his hand as an actor. Admittedly, he never played Hamlet, but he did play Duncan in his own production of Macbeth in 1940. Another character is Tomas Graal, a passing homage to two silent classics by Mauritz Stiller Thomas Graal's Best Film and Thomas Graal's Best Child. And the family name Ekdahl is a reference to the Ekdal family in Henrik Ibsen's The Wild Duck. When a journalist asked Bergman if this was a conscious reference, he confirmed that it was, adding 'but I didn't think anyone would notice!'

Fanny and Alexander has often been regarded as a summary of Bergman's entire career, and it undoubtedly contains most of the familiar elements from his other works: religion, the family, the role of the artist, etc. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that a number of familiar characters and names reappear: Vergérus is one of the recurring names in Bergman's films, and the Ekdahl family friend Isak Jacobi is almost identical to a character in an earlier play Unto My Fear, an 'ancient rabbi type'.

In the light of all this, it is fascinating that so much of Fanny and Alexander should be played out in a theatre environment, and with references to dramatists so close to Bergman's heart, such as Ibsen, Shakespeare and Strindberg. Despite his outstanding achievements as a filmmaker, Bergman has consistently maintained that he is first and foremost a theatre director, and much of Fanny and Alexander gives additional weight to his claims.

Shooting the film

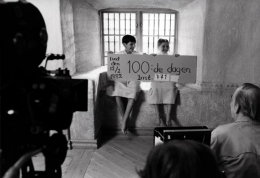

On 23 October 1980 the Swedish tabloid newspaper Expressen announced that 'Ingmar Bergman, 62, is once again to make a film in Sweden. Five years after the tax wrangle which caused him to leave Sweden he is planning his biggest ever production. The film is to be called: 'Fanny and Alexander' and will star Max von Sydow, Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann. Production costs: 35 million Swedish kronor.'

It was almost accurate. No news had yet been issued about the casting, so one can assume that the journalists had indulged in a spot of qualified guesswork. But of the actors they tipped, only Josephson actually played in the film, and then only in a minor role. And nobody at the time had any idea that production costs would exceed the figure that Expressen announced.

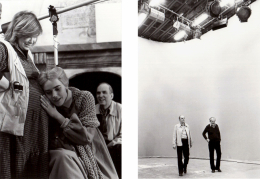

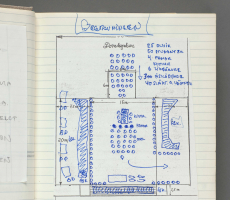

Shooting began on 7 September 1981 in the studios of the Swedish Film Institute in Stockholm's Filmhuset. It was to go on longer than any other of Bergman's films. Things got off to a good start, but then a series of catastrophes struck. Sven Nykvist and Bergman came within inches of their lives when an overhead crane came crashing to the floor. On another occasion the chief electrician broke both his legs. The makeup artist suffered a back injury and was unable to work. A stuntman caught on fire. And then came the influenza outbreak: it knocked out half the crew, director and cinematographer included!

Yet the shooting schedule had to be met, so the crew carried on with assistant director Peter Schildt and the cinematographer Tony Forsberg, a man who, according to Bergman was "underrated but first class". One of the scenes shot in the director's absence was the funeral of Oscar Ekdahl. Bergman, who had left detailed instructions, was pleased with the result.

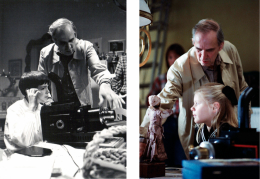

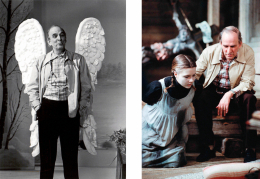

Universally hailed as an expert at getting the best out of a cast, Bergman has, along with W.C. Fields, admitted to having problems working with two types of actors, children and animals: 'they don't do what you say'. Yet Pernilla Allwin and Bertil Guve handled the title roles in exemplary fashion. Guve, a 'complete rascal' according to Bergman, had landed the role as Alexander thanks in no small measure to the fact that during the screen tests, when all the young hopefuls were asked to come up with something terrible that they had done, he had extravagantly claimed that: 'I murdered my grandfather!'

Although the children were excellent, the animals remained true to form. One of them, at least, found it hard to accept direction. Outside the bishop's house, a large black cat was supposed to stand guard. Anyone wanting to see what happened when the cat refused to obey the director can view entire incident in the behind-the-scenes film, Document Fanny och Alexander.

Originally Fanny and Alexander were to have had an older sister (sometimes called Amanda, sometimes Amalia), who was to be played by Bergman's daughter Linn Ullmann. But when she was refused time off school, the director scrapped the role entirely.

However, no fewer than three of Bergman's other children did take part in the film. Best known for his stage roles at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, Mats Bergman played only his third film role as Aron Retzinsky, the nephew of Isak Jacobi. His sister Anna, the model and actress, took the small part of Hanna Schwartz. And Daniel Bergman, who would later become a film director himself (of works including Sunday's Children), was one of the grips on the set.

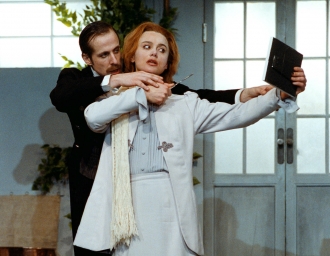

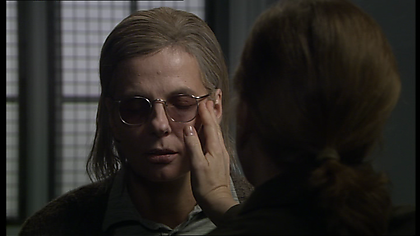

The role of the children's mother went to Ewa Fröling, who had recently enjoyed her breakthrough in the title role of Gunnel Lindblom's Sally and Freedom, a film which Bergman produced. Two years later she played Regan in Bergman's highly-acclaimed stage production of King Lear. The part of her second husband, Edvard Vergérus, was originally intended for Max von Sydow, yet his agent scuppered things by attempting to negotiate an unreasonably high fee. In his own opinion, it was the biggest ever mistake of von Sydow's career. The role went instead to Jan Malmsjö, whose only previous collaboration with Bergman had been in the small, yet eminently memorable role of Peter in Scenes from a Marriage. He would later play key roles in Bergman's valedictory stage productions, those of Strindberg's Ghost Sonata and Ibsen's Ghosts.

Jarl Kulle had previously played two unforgettable parts in Bergman's films: Count Malcolm in Smiles of a Summer Night and Doctor Farell in Alf Sjöberg's Last Couple Out, with a screenplay by Bergman. In his role as the hearty Gustaf Adolf Ekdahl, Kulle was in his element. So much so that many reviews considered it the best role of his career. It led to a renewal of his theatre career, including leading roles in Bergman's productions of King Lear and Long Day's Journey into Night. Gustav Adolf's brother Carl was played by Börje Ahlstedt, whose previous collaborations with Bergman had been modest to say the least (a part in the TV film The Lie, for which Bergman only wrote the screenplay, and a couple of stage roles). From Fanny and Alexander onwards, their relationship grew closer. Ahlstedt would later play the same part as Uncle Carl in The Best Intentions, Sunday's Children and In the Presence of a Clown, not to mention the principal role in Saraband. Bergman's close friend, Erland Josephson, the actor with whom he has worked most of all (twenty stage roles since 1940 and fifteen in films) played Isak Jacobi, a minor yet key part in the film.

Helena Ekdahl was played by one of the grand old dames of Swedish stage and film, Gunn Wållgren, an actress who had only worked with Bergman once before, way back in 1947, when she played the part of Kerstin in his production of Playing With Fire for Swedish radio theatre Radioteatern. Wållgren was seriously ill and in chronic pain throughout the shoot, "

and yet," as Bergman affectionately recalls, 'she managed a smile and a sprightly dance through the studio apartment, take after take.' And Gunnar Björnstrand, who had a very minor role, was suffering from the onset of Alzheimer's Syndrome, which gave him big problems remembering his lines. He managed in the end, and his role, though small, seems a fitting end to a long and shared professional career: 'My partnership with Gunnar,' Bergman has remarked, 'was one of the great experiences of my life.'

With 250 costumes for the actors and more than a thousand more for the extras, this was the biggest project ever for designer Marik Vos. She was especially appreciative of Bergman's commitment: every fabric sample was test filmed since they can appear differently on the screen from in the hand, and the director never tired of viewing all the small clips of film. On the contrary, he got angry when they neglected to show him Emilie's dressing gown. 'The costume is the actor's second skin' Bergman had insisted to Vos. And the costumes in Fanny and Alexander would later be recognised with an Oscar.

A further testament to Bergman's eye for detail during the shoot came when one of the props assistants produced an antique breakfast cup. Bergman praised this initiative with an enthusiastic exclamation: 'Yes, it's very classy, very dramatic too, bloody stylish!'

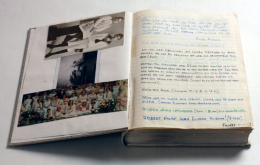

In all, the filming was extremely demanding both for the director and the entire crew. Yet nobody seems to recall the event with anything other than pleasure. Some fascinating insights into the filming can be gleaned from Bergman's small and carefully dated notes on a number of pages of the screenplay. They represent his potted version of the film shoot, its triumphs and setbacks:

God, let me not lose my joy. (3 Oct.)

Now I really yearn to stand protected by benign powers, if I am to complete my task. (15 Nov)

The night of Friday 27 Nov: I wake at half past one from a very deep and disagreeable sleep and don't know where I am. Suddenly start to feel as if I'm coming down with an infection. Relentless and total anguish. How can I protect myself from this horror! which is virtually suffocating me. Good God preserve my senses. (No basis, or at best a very scanty one, in reality!)

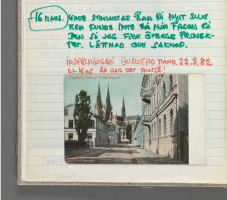

Bold and cheerful. (Saturday 19.12.81, at 13.50)

May I now come through this. May I have strength and joy. (Thursday 7 January after a dreadful night)

Bloody, bloody flu' (7 Jan 21 Jan) and other ailments.

Job fun once again good spirits have returned! (7 Feb)

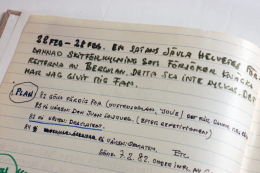

22 Feb 28 Feb. A bloody fucking hell of a bastard cold that's trying to destroy all that remains of Bergman. It will not succeed. I'm damned if it will.

Plan:

82 finish (The School for Wives, Julie) That's should bloody well be enough

83 spring: Don Juan Salzburg. (After the Rehearsal)

83 autumn: Royal Dramatic Theatre

84 spring: Royal Dramatic Theatre. Etc.

Sun. 7.2.82. under the influence of a good mood

16 March.

Had grand plan for a new ending but couldn't get to grips with it so I had to abandon the project. Relief and regret.

Filming completed Mon. 22.3.82, at 16.05. That was that, then!

In a press release prior to the launch of the film, Bergman made the following statement: 'After Fanny and Alexander there will be no more feature films for me. It could not be any more fun, nor any more painful either. Fanny and Alexander is like a summing up of my entire life as a filmmaker. Feature films are a job for young people, both physically and psychologically.'

Epilogue

When shooting was over it was time to go through the accumulated material, some 25 hours of film that was to be edited first into five episodes for television, then to a cinema version with a maximum length of 150 minutes. On 31 March 1982 Bergman wrote in his workbook:

'At last I am reviewing the rushes. The first day we sat through four hours of material. The result was indeed a mixed bag. At times I was rather shocked by what I saw. What I had thougt worked well, turned out to be bad, uneven, deplorable. Other things, I suppose, were passable. But nothing, except Gunn Wållgren, was really good.'

When Bergman and the editor Sylvia Ingemarsson had seen it all, they went through the 25 hours again and things started to feel better. The TV version turned out to be over five hours long, 326 minutes. Then it was time for the cinema version. Bergman writing in Images:

The idea was that we would quickly, in a few days, design the theater version that I already had planned out in my head. I knew rather clearly what I wanted to cut, and my goal was to end up with a two-and-a-half-hour film. We worked at a rapid pace. When we had finished, I discovered to my horror that I had a film almost four hours long. What a shock! I had always given myself credit for having an excellent sense of time and timing. There was nothing to do but start over from the beginning. It was extraordinarily troublesome, since I now had to cut into the vital parts of the film. I knew that with each cut I reduced the quality of my work. We finally ended up in a compromise: the film was three hours and eight minutes long.

He also claimed that the TV version was the one that showed his true vision, since the cinema version was merely a fragment, albeit for obligatory reasons. The shooting itself had been filmed by Arne Carlsson. From this behind-the-scenes material he and Bergman put together Document Fanny och Alexander.

In April 1984 Fanny and Alexander was awarded no fewer than four Oscars: for best foreign language film, best cinematography (Sven Nykvist), best art direction/set decoration (Anna Asp), and best costume design (Marik Vos). The award was received on his behalf by Bergman's wife, Ingrid, who, according to Nykvist, was very keen to meet Gregory Peck at the ceremony.

Fanny and Alexander marks the beginning of a new era in Bergman's artistic output. Admittedly, he never completely abandoned filmmaking, but he did concentrate instead on his writing, where he had begun his career. And thematically Fanny and Alexander was to be the first part of an ongoing family saga that with time came to assume almost epic proportions. A few years after the film's release he made a short film for television called Karin's Face, based around photographs of his mother.

At the same time he began to write his autobiography The Magic Lantern, followed in 1991 by the novel about his parent's marriage The Best Intentions (also filmed for television). The very next year saw a new film from a screenplay by Bergman, this time about the relationship between Bergman as a young boy and his father. The director of Sunday's Children was Bergman's own son Daniel Bergman. Sunday's Children was published as a book in 1993, following the release of the film. A few years later saw both the publication of Private Confessions and a TV adaptation of the novel.

When it was announced in 1999 that Liv Ullmann was to direct a film for television, Faithless, based on a screenplay by Bergman (also published as a book) Bergman felt obliged at the press conference to stress that it wasn't 'about my parents, aunts and uncles'. This time it was about himself!

Sources

- The Ingmar Bergman Archives.

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Jörn Donner, "Rätt ta risken och trotsa alla", Svenska Dagbladet, 15 December 1982.

- "Jag har försökt att ta kål på barnet i mig men det lever", Vi, 15 April 1982.

- "Bergman berättar om Fanny och Alexander", Aftonbladet, 26 December 1984.

By his own admission, Arnaud Desplechin had Fanny and Alexander in mind when he wrote A Christmas Tale. The timing (Christmas festivities) and five acts editing (yet another theatrical device) probably are borrowed from Bergman’s film. One scene is particularly reminiscent of it: when Faunia (Emmanuelle Devos) prays for her friend Henri, she clenches her hands, while a surreal white light floods the screen, and a violin chromatic scale is heard. In a 2008 interview, Arnaud Desplechin told me he had felt it was the most effective way to shoot this particular scene.

Finally, Michael Haneke’s White Ribbon, winner of the 2009 Cannes Palme d’Or, is reminiscent of three Bergman films. As in The Passion of Anna, unexplained criminal acts – among which a barn burning down – occur in a small and quiet village and are related by a voice-over. Like Pastor Tomas Ericsson in Winter Light, the local doctor, a widower, humiliates his mistress. Like Bishop Edvard Vergerus in Fanny and Alexander, the local puritanical pastor gives his pubescent children a guilty conscience over apparently small transgressions.

There is also a seeming kinship between Bergman’s last opus Saraband and Haneke’s latest work, Amour.

© Charlotte Renaud

[The "Legacy" section is written and compiled by Charlotte Renaud. Look here for heirs to other Bergman films.]

The Ekdahls are an upper-middle-class theatrical family who are sheltered by their own theatrics from the deepening chaos of the outside world. Bergman has the grace in this most graceful film not to view their histrionics and eccentricities as neuroses.

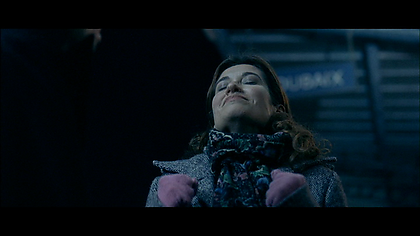

One tumultuous year in the life of the Ekdahl family is viewed through the eyes of ten-year-old Alexander, whose imagination fuels the magical goings-on leading up to and following the death of his father. His mother's remarriage to a stern prelate banishes Alexander and his sister Fanny from all known joys, and thrusts them and the movie into a kind of gothic horror.

The bishop is a Bergmanesque character whose severity has gone awry – he has become sinister – and the film's round rejection of him in favor of "kindness, affection and goodness" may be Bergman's fondest farewell to cinema.

Distribution titles

Fanni i Aleksand'r (Bulgaria)

Fanny and Alexander (Great Britain)

Fanny and Alexander (USA)

Fanny ja Alexander (Finland)

Fanny og Alexander (Denmark)

Fanny og Alexander (Norway)

Fanny y Alexander (Spain)

Fanny et Alexandre (France)

Fanny und Alexander (West Germany)

Production details

Production country: Sweden, France, West Germany

Swedish distributor (35 mm): Sandrew Film & Teater AB

Laboratory: FilmTeknik AB

Production company: Cinematograph AB, Svenska Filminstitutet, Sveriges Television AB TV1, Gaumont International,

Personafilm GmbH, Tobis Filmkunst GmbH

Aspect ratio: 1,66:1

Colour system: Eastman Color

Sound system: Optical mono

Original length (minutes): 188

Censorship: 123.776

Date: 1982-12-09

Age limit: 11 years and over

Length: 5155 metres

Release date: 1982-12-17, Royal, Göteborg, Sweden, 188 minutes

Sandrew 1, Helsingborg, Sweden

Sandrew 1, Malmö, Sweden

Astoria, Stockholm, Sweden

Sandrew 1, Södertälje, Sweden

Sandrew 1, Umeå, Sweden

Sandrew 1, Uppsala, Sweden

TV-screening: 1999-12-26, TV4, Sweden, 180 minutes

Filming locations

Uppsala, Sweden

Filmhuset, Gärdet, Stockholm, Sweden

Music

Title: Den gång jag var...

Lyrics: Allan Bergstrand

Title: Sonat, piano, op. 35, b minor, "Marche funèbre"

Composer: Frédéric Chopin (1837-1839)

Orchestra: Stockholm Regionmusikkår

Orchestra manager: Per Lyng

Title: Tretonsmusik

Composer: Daniel Bell

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Symfoni, no 4, op 120, d minor. Movement 2

Composer: Robert Schumann (1841, rev. 1851)

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Hebreisk song from the 17th century

Singer: Stina Ekblad

Title: An der schönen blauen Donau, op. 314

Composer: Johann Strauss, jr. (1867)

Comment: Instrumental - music box.

Title: Suite No 3 for Cello Solo

Composer: Benjamin Britten

Instrumentalist: Frans Helmerson (cello)

Cembalomusik

Composer: Allan Edwall

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Suite No 2 for Cello Solo

Composer: Benjamin Britten

Instrumentalist: Frans Helmerson (cello)

Title: O Tannenbaum, O Tannenbaum

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Sonat, fluite, cembalo, BWV 1031, Eb major

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Instrumentalist: Gunilla von Bahr (fluit)

Title: Du Ring an meinem Finger

Composer: Robert Schumann

Lyrics: Adalbert von Chamisson

Singer: Christina Schollin

Title: Smålandsvisan

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: La Belle Hélène

Composer: Jacques Offenbach

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Es ist ein Ros' entsprungen

Lyrics: Thekla Knös (1867)

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Title: Nocturne, nr 7, op. 27:1, ciss minor

Composer: Frédéric Chopin (1834-35)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Helan går

Singer: Allan Edwall

Singer: Jarl Kulle

Singer: Börje Ahlstedt

Title: Hej, tomtegubbar ...

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Singer: Börje Ahlstedt

Singer: Jarl Kulle

Singer: Allan Edwall

Title: Nu är det jul igen ...

Singer: Choir

Title: Bagatell, piano

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei (piano)

Title: Humoresk, piano, op. 101. No 7, Gb major

Composer: Antonín Dvořák (1894)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Impromptu, piano, D. 935, op. 142. Nr 3, B major

Composer: Franz Schubert (1827)

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Finska Rytteriets marsch

Lyrics: Zacharias Topelius

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Instrumentalist: Käbi Laretei (piano)

Title: Den signade dag

Lyrics: Johan Olof Wallin (1812)

Arrangement: Johan Olof Wallin (1812)

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Slutackord - teatern

Composer: Daniel Bell

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: A Tailor and His Wife

Comment: Sung by choir (the student friends).

Title: Triumfmarsch

Composer: Giuseppe Verdi

Arrangement: Daniel Bell

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Kvintett, stråkar, piano, op. 44, Eb major

Composer: Robert Schumann (1842)

Instrumentalist: Marianne Jacobs (piano)

Instrumentalist: Freskkvartetten

Title: Konsert, mandolin (2), string orchestra, RV 532, G major

Composer: Antonio Vivaldi

Comment: Instrumental.

Title: Ängelmusik

Composer: Daniel Bell

Collaborators

- Kristina Adolphson, Siri

- Börje Ahlstedt, Carl Ekdahl

- Pernilla Allwin, Fanny Ekdahl

- Kristian Almgren, Putte Ekdahl

- Carl Billquist, Police superintendent Jespersson

- Axel Düberg, The witness

- Ebba Edstrand, Aurora, newborn child of Edvard and Emilie

- Allan Edwall, Oscar Ekdahl

- Siv Ericks, Alida

- Ewa Fröling, Emilie Ekdahl

- Patricia Gélin, The statue

- Majlis Granlund, Vega

- Maria Granlund, Petra Ekdahl

- Bertil Guve, Alexander Ekdahl

- Eva von Hanno, Berta

- Sonya Hedenbratt, Aunt Emma

- Olle Hilding, Priest at christening ceremony

- Svea Holst

- Jarl Kulle, Gustav Adolf Ekdahl

- Käbi Laretei, Aunt Anna von Bohlen

- Linnéa Linder, Helena Victoria

- Mona Malm, Alma Ekdahl

- Lena Olin, Rosa

- Gösta Prüzelius, Dr. Fürstenberg

- Christina Schollin, Lydia Ekdahl

- Hans Strååt, Pastor of marriage ceremony

- Angelica Wallgren

- Pernilla August, Maj Kling

- Emelie Werkö, Jenny Ekdahl

- Gunn Wållgren, Helena Ekdahl

- Inga Ålenius, Lisen

- Georg Årlin, The colonel

- Marianne Aminoff, Blenda Vergérus

- Harriet Andersson, Justina

- Mona Andersson, Karna

- Linda Krüger, Pauline

- Hans Henrik Lerfeldt, Elsa Bergius

- Jan Malmsjö, Bishop Edvard Vergérus

- Marianne Nielsen, Selma

- Marrit Ohlsson, Malla Tander

- Kerstin Tidelius, Henrietta Vergérus

- Pernilla Wahlgren, Esmerald, the bishop's dead daughter

- Anna Bergman, Mrs Hanna Schwartz

- Gunnar Björnstrand, Filip Landhal

- Mattias Bolliger

- Nils Brandt, Mr Morsing

- Lars-Owe Carlberg

- Gus Dahlström, Stage manager

- Ernst Günther, rector magnificus

- Hugo Hasslo, Carl's singing partner

- Heinz Hopf, Tomas Graal, actor

- Maud Hyttenberg, Miss Sinclair

- Sven-Erik Jacobsson

- Marianne Karlbeck, Miss Palmgren

- Kerstin Karte, the Prompter

- Tore Karte, Office manager

- Åke Lagergren, Johan Armfeldt, actor

- Sune Mangs, Mr Salenius, actor

- Per Mattsson, Mikael Bergman (plays the part of Hamlet)

- Marie Louise Sid, Dancer

- Lickå Sjöman, Grete Holm

- Ryno Wallin

- Daniel Bell

- Gunnar Djerf, Member of theatre orchestra

- Ebbe Eng, Member of theatre orchestra

- Folke Eng, Member of theatre orchestra

- Evert Hallmarken, Member of theatre orchestra

- Nils Kyndel, Member of theatre orchestra

- Ulf Lagerwall, Member of theatre orchestra

- Börje Mårelius, Member of theatre orchestra

- Karl Nilheim, Member of theatre orchestra

- Erland Josephson, Isak Jacobi

- Stina Ekblad, Ismael Retzinsky

- Mats Bergman, Aron Retzinsky, Nephew of Isak

- Viola Aberlé, Japanese woman

- Gerd Andersson, Japanese woman

- Ann-Louise Bergström, Japanese woman

- Marie-Hélène Breillat

- Peter Stormare, Young man helping Jacobi with chests

- Krister Hell, Additional Casting

- Ingrid Bergman, Administration

- Susanne Lingheim, Propman

- Percy Nilsson, Construction Coordinator

- Åke Dahlbom, Driver

- Kristina Makroff, Costume Supervisor

- Elsie-Britt Lindström, Costumer

- Robert Nordlund, Costumer

- Kjell S. Koppel, Costumer

- Arne Högsander, Puppet Execution

- Jakob Tigerschiöld, Draftsman

- Ulf Björck, Gaffer

- Torbjörn Andersson, Gaffer

- Ted Lindahl, Gaffer

- Kent Högberg, Gaffer

- Ragnar "Pelka" Hansson, Gaffer

- Tony Forsberg, Second Unit Cameraman

- Sven Nykvist, Director of Photography

- Lars Karlsson, Assistant Cameraman

- Dan Myhrman, Assistant Cameraman

- Cecilia Drott, Hair Stylist

- Kjell Gustavsson, Hair Stylist

- Mariann Virdestam, Hair Stylist

- Brita Werkmäster, Unit Manager

- Eva Ivarsson, Unit Manager

- Sylvia Ingemarsson, Film Editor

- Anne-Marie Broms, Assistant Costume Designer

- Lenamari Wallström, Assistant Costume Designer

- Ingabritt Adrianson, Assistant Costume Designer

- Maria "Tobbe" Lindmark, Assistant Costume Designer

- Marik Vos, Costume Designer

- Kerstin Eriksdotter, Continuity

- Mercedes Björlin, Choreography

- Owe Svensson, Production Mixer

- Bo Persson, Production Mixer

- Björn Gunnarsson, Production Mixer

- Lars Liljeholm, Production Mixer

- Nils Melander, Color Timer

- Barbro Holmbring, Make-up / Hair

- Leif Qviström, Make-up / Hair

- Anna-Lena Melin, Make-up / Hair

- Rolf Persson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Anna Skagerfors, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Cecilia Iversen, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Lisbet Jansson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Anna Marie "Ami" Davidsson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Tua Ekholm, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Bengt Landegren, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Tom Stocklassa, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Bengt Svedberg, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Sigrid William-Olsson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Kent Ericsson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Thomas Olsson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Ylva Hammar, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Teddy Holm, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Dick Jacobsson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Andrew Jones, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Donald Karlsson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Lena Karlsson, Painter / Scenic Artist

- Daniel Bergman, Key Grip

- Ulf Pramfors, Key Grip

- Berit Gullberg, Press Agent

- Jörn Donner, Producer

- Hellen Igler, Production Accountant

- Katinka Faragó, Production Manager / Production Coordinator

- Benita Lundqvist, Production Secretary

- Peter Schildt, Assistant Director

- Jan Andersson, Property Master

- Gunilla Allard, Property Master

- Christer Ekelund, Property Master

- Johan Husberg, Property Master

- Anna Asp, Production Designer

- Kaj Larsen, Production Designer

- Ann-Margret Fyregård, Assistant Production Designer

- Ulrika Rindegård, Assistant Production Designer

- Jan Eriksson, Carpenter

- Kenneth Blomqvist, Carpenter

- Hans Strandberg, Carpenter

- Björn Sinclair, Carpenter

- Nils-Olof Johansson, Carpenter

- Olle Bergh, Carpenter

- Bertil Sjölund, Carpenter

- Anders Söderlund, Carpenter

- Berth Martinson, Carpenter

- Martti Malkamaa, Carpenter

- Bengt Lundgren, Special Effects

- Arne Carlsson, Still Photographer

- Solveig Eriksson, Dressmaker

- Wiveca Dahlström, Dressmaker

- Ann-Katrin Edmark, Dressmaker

- Rosemarie Karlsson, Dressmaker

- Lena Persson, Dressmaker

- Caroline von Rosen, Dressmaker

- Nicklas Svartengren, Dressmaker

- Johan Thorén, Other Crew

- Marie Rechlin, Other Crew

- Fredrik von Rosen, Other Crew

- Christian Wirsén, Other Crew

- Mildred Brandt, Other Crew

- Ingmar Bergman, Screenplay