Wild Strawberries

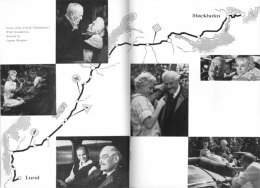

Professor Isak Borg re-evaluates his life during a road-trip between Stockholm and Lund.

"Who can forget such images?"Woody Allen

About the film

Winter 1956-1957 was a time of intensive and fruitful labour for Bergman. The summer had been devoted to The Seventh Seal, followed by three productions at the Malmö City Theatre: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Erik XIV and Peer Gynt. But his general health was poor. As spring approached he was admitted to Stockholm's Karolinska University Hospital where he remained for almost two months 'for general observation and treatment.' It was during this period that he wrote the screenplay for Wild Strawberries.

In an interview from the 1960s he speaks of a journey to Dalarna during the autumn of 1956 when he stopped off in Uppsala at his grandmothers' house on Slottsgatan [though in fact it was Trädgårdsgatan]. He was overcome by a particular feeling: just imagine if the old cook Lalla were to open the door, just as she had done so many times before?

Then it struck me: supposing I make a film of someone coming along, perfectly realistically, and suddenly opening a door and walking into his childhood? And then opening another door and walking out into reality again? And then walking round the corner of the street and coming into some other period of his life, and everything still alive and going on as before? That was the real starting point of Wild Strawberries.

Later he would revise the story of the film's genesis. In Images: My Life in Film he comments on his own earlier statement: 'That's a lie. The truth is that I am forever living in my childhood.'

Nevertheless, the screenplay was begun in earnest during his stay in hospital in the spring of 1957. The project had been given the seal of approval by Carl Anders Dymling, who had been shown a short synopsis. Bergman's doctor at Karolinska was his good friend Sture Helander, who invited Ingmar to attend his lectures on psychosomatics. Helander was married to Gunnel Lindblom who was to play Isak's sister Charlotta in the film. In general, casting and other preparations seem to have progressed with remarkable speed, since the completed screenplay is dated 31 May and shooting began on 2 July. The fact that many of the actors came from the Malmö City Theatre company probably helped in the process.

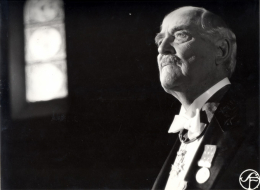

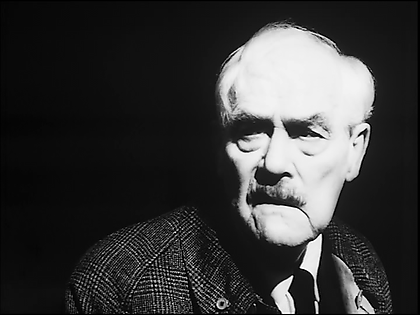

The casting of the heavyweight principal role – Isak Borg – is a story in itself. Given that Wild Strawberries is probably the one film of Bergman that bears the closest relationship with his favourite film The Phantom Carriage, one might imagine that the participation of Victor Sjöström was planned from an early stage. Yet this does not appear to be the case. In Bergman on Bergman he has stated that he only thought of Sjöström when the screenplay was complete, and that he asked Dymling to contact the great man. Yet in Images: My Life in Film he claims that: 'It is probably worth noting that I never for a moment thought of Sjöström when I was writing the screenplay. The suggestion came from the film's producer, Carl Anders Dymling. As I recall, I thought long and hard before I agreed to let him have the part.' We shall never know the true story, but in the finished film, Sjöström's role was of fundamental importance.

Sources of inspiration

Of all Bergman's works, Wild Strawberries is one of the most widely imitated and referred to (see below). It is also one of only a few films in which Bergman's own sources of inspiration and creative borrowings are most clearly discernible.

The influences of August Strindberg – widespread in Bergman – are immediately apparent. Strindberg's introduction to A Dream Play (which is later quoted openly in Fanny and Alexander) might also appear to be the credo of Wild Strawberries:

Time and space do not exist. Upon an insignificant background of real life events, the imagination spins and weaves new patterns; a blend of memories, experiences, pure inventions, absurdities and improvisations.

Given that during the five years prior to Wild Strawberries Bergman produced no fewer than three Strindberg plays (The Crown Bride, Ghost Sonata, Erik XIV) the affinities are hardly surprising. Strindberg's sworn enemy Henrik Ibsen also appears to have had a key influence on Wild Strawberries. Not least Peer Gynt, which Bergman had produced just before he wrote the screenplay for the film. Like the eponymous hero of that play, Isak in Wild Strawberries takes stock of his life.

The many borrowings of the film were noted in one of the few negative reviews it received, criticising the film for too many literary references and a lack of originality:

From the Ibsen era comes the old cliché about the living who are actually dead. From His Lord's Will [Hjalmar Bergman's Hans nåds testamente] the amusing quarrels with the faithful servant. In skilfully contrived dream sequences the influence of Pär Lagerkvist can be discerned, when Strindberg is not making his contributions with the distinguished academic who is forced to undergo a viva.

As mentioned, one obvious cinematic influence is Sjöström's The Phantom Carriage, the film which, according to Bergman, was: the film of all films. 'I saw it for the first time when I was fifteen; to this day I see it at least once every summer, either alone or in the company of younger people. I clearly see how The Phantom Carriage has influenced my own work, right down to minute details.'

The first dream sequence, with its funeral - albeit without a driver - is a clear example of the influence of Sjöström, as is the clock without hands, which can be found in Karin Ingmarsdotter. But the most obvious celebration of his cinematic hero is naturally the appearance in the film of the man himself. According to Bergman, Sjöström 'took my text, made it his own, invested it with his own experiences':

[...] loneliness, coldness, warmth, harshness, and ennui. Borrowing my father's form, he occupied my soul and made it all his own - there wasn't even a crumb left over for me! He did so with the sovereign power of a gargantuan personality. I had nothing to add, not even a sensible or irrational comment. Wild Strawberries was no longer my film; it was Victor Sjöström's!

Apart from obvious borrowings from other works, the inspiration for Wild Strawberries can also be traced to Bergman's more personal experiences. As usual, Bergman himself is forthcoming with his own biographical details, not least in this case his relationship with his parents, a relationship that was particularly troubled at around this period: 'I tried to put myself in my father's place and sought explanations for the bitter quarrels with my mother. [...] Isak Borg equals me. I B equals Ice and Borg (the Swedish word for fortress). Simple and facile. I had created a character who, on the outside, looked like my father, but was me, through and through'

The painful identification with the father from whom he had distanced himself is central to the razor-sharp portraits of Isak Borg and his world-weary son, Evald. And the presentation of one and the same person as both old and young is a theme dear to Bergman's heart right up to his very latest works. The theme can be traced back to the prose work Bo Dahlin's notes on the divorce of parents (1951), which contains a scene between a jealous son and his mother's lover. Maaret Koskinen has recognised this as one of the familiar stylistic devices in Bergman's work's: 'At times, one gets the impression that Bergman himself has, in places, confronted a younger and older version of one and the same ego, who enter a conversation between themselves (also a favourite device in later works).'

Another, more intriguing source for the device of portraying oneself in two versions can be found in an entertaining article by Bergman in the popular Swedish magazine Se, written shortly before the filming of Wild Strawberries. The article is an ironic self portrait based around an alleged event at the Cannes Film Festival, where they played 'festival roulette with my film Smiles of a Summer Night.' A Russian artist asked if he could draw Bergman's portrait, placing his subject half turned towards a large mirror:

'After a while the picture was finished and I was allowed to see it. There were two Bergmans: one, as it were, direct, and one in the mirror. The first had a childish, almost foolish expression on his face. The image in the mirror was of an old man, a ghost with a weary look.'

It is hard not to regard one of the key scenes of Wild Strawberries, a dream sequence where Isak is forced to look at himself in a mirror held up by Sara, in which he sees an old man, in the light of this anecdote. Whether or not it is actually true is of minor significance.

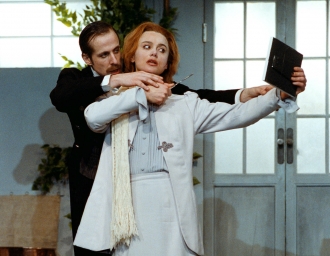

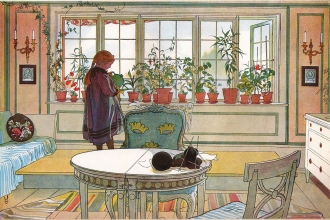

Finally, one may also speculate as to whether a number of well-known paintings provided the inspiration for some of the shots in the film (although this has never been confirmed by Bergman). The dream sequence scene in which Isak Borg is forced to witness his wife's infidelity bears both pictorial and thematic similarities with Edvard Munch's 'Jealousy'. And some of the more idyllic scenes of childhood bear distinct parallels with Carl Larsson's 'Crayfishing'.

Shooting the film

Shooting began on 2 July 1957, and took place for the most part at the Filmstaden studios in Råsunda, just outside Stockholm. A couple of scenes were filmed in Stockholm's old town, Gamla Stan, and scenes from the car journey were shot on location: Slussen in Stockholm; Gränna (including lunch at the Gyllene Uttern restaurant); Dalarö and Ägnö in the Stockholm archipelago; and at the University Square in Lund

During the shooting, the health of the 79-year-old Sjöström gave cause for concern. Dymling had persuaded him to take on the role with the words: 'All you have to do is lie under a tree, eat wild strawberries and think about your past, so it's nothing too arduous.' But in the event, it proved to be rather demanding. During the first few days Sjöström had problems with his lines, which made him frustrated and angry. To unburden his revered mentor, Bergman made a pact with Ingrid Thulin that if anything went wrong during a scene, she would take the blame on herself. Things gradually got better, especially when they changed filming times so that Sjöström could get home in time for his customary late afternoon whisky at 4.30. And the old charmer's obvious delight at playing opposite the 22-year-old Bibi Andersson was another plus.

Sjöström's presence on the set was also a source of entertainment and cinema history education for the team. In Bergman's words: 'Victor Sjöström was an excellent storyteller, funny and engaging – especially if some young, beautiful woman happened to be present. We were sitting at the very source of film history, both Swedish and American.'

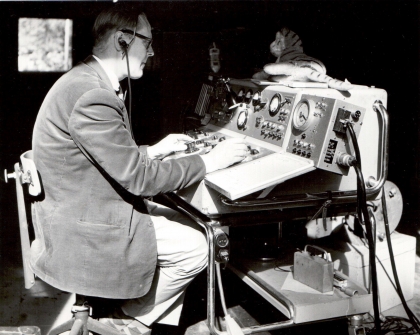

The film's cinematographer was Gunnar Fischer. Recalling the famous, deliberately over-exposed nightmare scene at the start of the film, Fischer has observed that he and Bergman attempted to intensify the impact of the nightmare with the light effects.

We agreed we would try to create hard images, try to eradicate all the softness of the grey scales. And unusually enough, I managed to acquire a few metres of spare film to experiment with. In general we had to make do with a bare minimum of film[...] I think I opted for a very fast, light-sensitive film. And then we were lucky with the street we were about to film. The sunlight was very strong indeed, ideal for the kind of black and white images we wanted. Yet when we returned after lunch the sun had moved – as it does – right in the middle of the street was the shadow of a large birch tree. What could we do? I could hardly contact the studio and say: 'Can you saw down that birch tree?' Maybe you can do that sort of thing in Hollywood, but not in Stockholm. I don't remember what we did exactly, but you can still notice that shadow at times.

The nightmare sequence was shot for the most part in the Filmstaden studios, apart from a couple of takes of the funeral, which were filmed in Gamla Stan at around two o'clock in the morning (there is clear daylight at that time of the year in Stockholm). According to Fischer, the crew suddenly heard the cheery song of revellers on their way home from a night on the town. When they caught sight of a funeral coming towards them without a driver, their singing quickly fell silent.

One of the most peculiar incidents during the shooting of the film involves the many hundreds of snakes that were intended to serve as extras in the dream scene where Isak witnesses his wife's infidelity. 'Wherever I looked it seemed that snakes were coming to life, springing out of the porous, swamp-like earth.'

It was probably just as well that the scene never came off, since the symbolism of the snakes would have been so overtly Freudian. But the actual reason why the snakes never featured in the film is worth recounting: the night before shooting they had all escaped from the terrarium in which they were being held and moved off into the neighbouring woods.

Epilogue

Filming came to an end on 27 August 1957, and the technical work started almost immediately. Oscar Rosander was the principal editor. The film was premiered in seven Swedish cities on 26 December 1957. The reviews were keenly enthusiastic, with one or two exceptions.

The film was selected to compete at the Berlin Film Festival, where it won the Golden Bear Award as Best Film. Reporting for Cahiers du cinéma, Jean-Luc Godard's short telegram to the home office is worth quoting: 'Golden Bear Wild Strawberries proves Ingmar greatest stop script fantastic about flas conscience Victor Sjöström dazzled beauty Bibi Andersson stop multiply Heidegger by Giraudoux get Bergman stop.'

Wild Strawberries remains Bergman's most successful film in terms of the number of awards it has received, and it firmly established Bergman's reputation as a filmmaker on the international stage.

With the possible exception of The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries is the Bergman film that other filmmakers have referred to most. Philip and Kersti French have even described it as 'the real ur-road movie', claiming that other films in the genre – such as Easy Rider – owe an implicit debt to Bergman's film. This may be an exaggeration, but whether in the form of parody or homage, there are numerous references to Wild Strawberries in the films of directors as diverse as Pedro Almodóvar (High Heels), André Téchiné (My Favourite Season), David Cronenberg and Tim Burton. Yet the most tireless devotee of the film is surely Woody Allen, who has made at least three films that – wholly or in part – be seen as appendages to Wild Strawberries: Another Woman, Crimes and Misdemeanors and Deconstructing Harry.

Finally, given that Bergman himself has said that he attempted to model Isak Borg on his own father, with whom he was in bitter feud at the time, it is interesting to see Bergman senior's reaction to the film. In a letter to its leading actor he wrote:

Dear Victor Sjöström!

Permit me, Ingmar's father, to send you my respectful greetings and my heartfelt thanks for your brilliant performance in Ingmar's latest film. – And thank you for all you have given to Ingmar and to me, and to countless others through your noble artistry and the spiritual inspiration of your entire work. – I will always remember with gratitude the friendly, encouraging words you spoke to me about Ingmar when he was still very young, and I stood before you in doubt and uncertainty.

My wife joins me in expressing our warm thanks.

Respectfully yours

Erik Bergman

4/1 58

Sources

- Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film.

- Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern.

- Ingmar Bergman, "Ingmars självporträtt", SE, no.9, 3 March 1957.

- Stig Björkman, Torsten Manns & Jonas Sima, Bergman on Bergman, (New York: Da Capo P., 1993).

- Bengt Forslund, Victor Sjöström: Hans liv och verk, (Stockholm: Bonniers, 1980).

- Philip French & Kersti French, Wild Strawberries, (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

- Maaret Koskinen, I begynnelsen var ordet, (Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 2002).

- Mårten Blomkvist, Interview with Gunnar Fischer before the screening of Wild Strawberries on Cinemateket 10th of May 2003.

Two sequences of Wild Strawberries are frequently quoted: 1) the first nightmare, during which Isak Borg dreams he is lost in a sunny empty street, and, after a look at a clock without hands, finally meets a man, who collapses; 2) the family lunch scene, as remembered by old Isak many years later. Both scenes seem influenced by August Strindberg, whose introduction to A Dream Play might be the credo of Wild Strawberries (it will later be openly quoted in Fanny and Alexander):

Time and space do not exist. Upon an insignificant background of real life events, the imagination spins and weaves new patterns; a blend of memories, experiences, pure inventions, absurdities and improvisations.

Given that during the five years prior to Wild Strawberries Bergman produced no fewer than three Strindberg plays (The Crown Bride, Ghost Sonata, Erik XIV) the affinities are hardly surprising.

1. Nightmare Scene

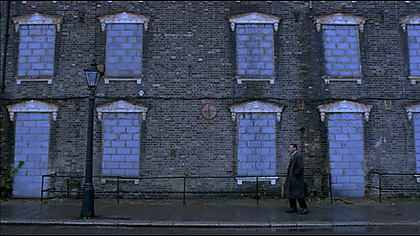

In the beginning of David Cronenberg's Spider, Dennis Cleg (Ralph Fiennes) roams a derelict urban area reminiscent of Isaac’s opening nightmare:

In the nightmare sequence of Desplechin's Esther Kahn, Esther dreams of a sunny, deserted street, whose doors and windows are all closed. She meets a faceless man, who suddenly collapses. Later in the movie, Esther, like Isak in Wild Strawberries, is said to be "dead, hard and cold".

© Charlotte Renaud

[The "Legacy" section is written and compiled by Charlotte Renaud. Look here for heirs to other Bergman films.]

Woody Allen in "Through a Life Darkly", The New York Times, 18 September, 1988:

Only in the late 50's, when I took my then wife to see a much talked about movie with the unpromising title Wild Strawberries did I look into what was to become a lifelong addictions to the films of Ingmar Bergman. I still recall my mouth dry and my heart pounding away from the first uncanny dream sequence to the last serene close-up. Who can forget such images? The clock with no hands. The horse-drawn hearse suddenly becoming stuck the blinding sunlight and the face of the old man as he is being pulled into the coffin with his own dead body. Clearly here was a master with an inspired personal style; an artist of deep concern and intellect, whose films would prove equal to great European literature.

Distribution titles

Les fraises sauvages (France)

Fresas salvajes (Spain)

Jordbærstedet (Denmark)

Mansikkapaikka (Finland)

Il posto della fragole (Italy)

Ved vejs ende (Norway)

Wild Strawberries (Great Britain)

Wild Strawberries (USA)

Wilde Erdbeeren (West Germany)

Wilde Erdbeeren (Austria)

Production details

Production country: Sweden

Swedish distributor (35 mm): Svensk Filmindustri, Svenska Filminstitutet

Swedish distributor (video for rental and sale) (physical): Svenska Filminstitutet

Laboratory: FilmTeknik AB

Production company: Svensk Filmindustri

Aspect ratio: 1,37:1

Colour system: Black and white

Sound system: Optical mono

Original length (minutes): 91

Censorship: 091.290

Date: 1957-12-16

Age limit: 15 years and over

Length: 2490 metres

Release date: 1957-12-26, Röda Kvarn, Helsingborg, Sweden, 91 minutes

China, Jönköping, Sweden

Röda Kvarn, Linköping, Sweden

Fontänen, Malmö, Sweden

Scania, Malmö, Sweden

Skandia, Norrköping, Sweden

Fontänen, Stockholm, Sweden

Röda Kvarn, Stockholm, Sweden

Röda Kvarn, Uppsala, Sweden

Filming locations

Filmstaden, Råsunda, Stockholm.

Gyllene Uttern near by Gränna.

Slussen, Stockholm.

Dalarö and Ängsö in the Stockholm archipelago.

Universitetsplatsen, Lund.

Music

''Fuga i ess-moll'' – Johann Sebastian Bach),

''Kungliga Södermanlands Regementes marsch'' – Carl Axel Lundvall

''Marcia Carolus Rex''

''Parademarsch der 18:er Husaren'' – Alwin Müller

''Under rönn och syrén/Blommande sköna dalar'' – Herman Palm, lyrics Zacharias Topelius

''Ja, må han leva!''.

Isak: Our relation with other people mainly consist of discussing and judging our neighbours' character and behaviour. For me, this has led to a voluntary withdrawal from virtually all so-called intercourse. Owing to this, I have become somewhat lonely in my old age. These days of my life have been full of hard work, and for this I'm grateful. What began as a struggle to make a living ended in a passion for science

Isak: Perhaps I should also add that I'm confirmed pedant. Something which at times has been rather trying for both myself, and those who've been obliged to live alongside me. My name is Eberhard Isak Borg, and I'm seventy-eight years old

Fröken Agda: Just go ahead and ruin the most solemn day of my life.

Isak: We're not married, Miss Agda.

Fröken Agda: I thank the lord every night that I'm not married to the professor. All my life I've trusted my judgement and I'll do so today.

Isak: Is that your last word on the matter?

Fröken Agda: That is my last word. I have lots to say to myself about old mean men who think only of themselves and not at all of others who've served them loyally for forty years.

Isak: It's beyond my grasp why I've put up with your despotism all these years, Miss Agda.

Isak: Now take the cigar. Cigars are an expression of the fundamental idea of smoking. A stimulant and a relaxation. A manly vice.

Marianne: And what vices may a woman have?

Isak: Crying, bearing children, and gossiping about the neighbours.

Marianne: How old are you, Uncle Isak?

Isak: Why do you ask?

Marianne: No reason, really. Why?

Isak: I know why you're asking.

Marianne: If you say so

Isak: What exactly have you against me?

Marianne: Do you want an honest answer?

Isak: I'm asking you.

Marianne: You're an inveterate egotist, Uncle Isak. You're completely ruthless; you've never listened to anyone but yourself. It's well-masked by your old man's mask and your amiability. But you're an inflexible egotist. The world may see you as a great philanthropist. We who've seen you at close quarters know better. You can't fool us.

Isak: It's possible that I became a bit sentimental. Perhaps I was a bit tired and felt a trifle melancholy. It's not inconceivable that I came to think of a thing or two associated with the places where we played as children. I don't know how it happened, but the day's clear reality flowed into dreamlike images. I don't even know if it was a dream, or memories which arose with the force of real events.

Sara: We've got a ride almost all the way to Italy. This is Anders. And that's Viktor, Vic for short. And this is father Isak. The looker you're ogling like crazy is Marianne.

Alman: Are you all right? We have no excuse. We're entirely to blame. My wife was driving,

Alman: That's my wife, Berit. She used to be an actress. We were discussing that when

Come here and apologise!

Berit: I'm so sorry, it was entirely my fault. I was about to punch my husband when that bend appeared. Your sins will find you out. Right, Sten? You're Catholic.

Isak: How is your leg?

Alman: It's not from this. I've been crippled for years. Unfortunately it's not only my leg that's crippled, according to my wife.

Berit: Now watch the engineer closely, see how he matches his strength with the young boys, how how tenses his feeble muscles to impress the pretty girl. Sten darling, watch out that you don't have a hemorrhage.

Alman: My wife loves to embarrass me in front of strangers. I let her it's psychotherapy.

Alman: I can never tell if my wife is really crying or putting on an act. Dammit, I think these are real tears.

Sara: Have you looked yourself in the mirror, Isak? You haven't. Then Ill show you how you look.

Alman: Moreover, you are guilty of guilt.

Isak: Guilty of guilt?

Alman: I have noted that you don't understand the accusation.

Isak: Is it serious?

Alman: Unfortunately, Professor.

Viktor: How could a modern man be a cleric? Anders isn't that thick.

Marianne: Why don't your leave your wife be?

Alman: Do not trifle with women's emotions, for they are holy. You're a very attractive woman. Old Berit is a bit shabby, so you can afford to defend her.

Marianne: I sympathise with your wife for many reasons

Alman: A most sarcastic remark. And you don't seem hysterical in the least. Little Berit here is a classical hysteria. Do you know what that means?

Marianne: Your wife says you're a Catholic.

Alman: Exactly, that's how I bear it; I ridicule my wife, and she me. She has her hysterics and I have my Catholicism. But we need each other's company. It's only out of pure selfishness that we haven't murdered each other by now.

Marianne: Did you sleep well?

Isak: Yes, but I dreamt. This past month I've been having the oddest dreams. It's quite comical.

Marianne: What is?

Isak: It is as if I am telling myself something I don't want to hear when I am awake.

Marianne: What would that be?

Isak: That I'm dead

even though I'm alive.

Evald: Its absurd to live in this world, but it's even more ridiculous to populate it with new victims and it's most absurd of all to believe that they will have it any better than us.

Marianne: You're making excuses.

Evald: Call it what you want. Personally I was an unwelcomed child in a marriage which was a nice imitation of hell.

Evald: This life disgusts me and I don't think that I need a responsibility which will force me to exist another day longer than I want to.

Judy Bloch, 2004:

Wild Strawberries unites two strands in Bergman's work: here, the examination of male vanity finds its apex, and the protagonist is introduced to a rather severe comeuppance in the face of death. Bergman does it with mirrors, and with dreams, which are the mind's mirror. Interestingly, the film's Dali/Kafkaesque dream sequences have proved less memorable than the scenes in which natural settings are brilliantly transformed into dreamscapes by virtue of their flashback context.

Honoring his debt to the early Swedish cinema and the oneiric quality of its nature cinematography, Bergman cast the great silent film director and actor Victor Sjöström as the aging pedant, Isak Borg, who dreams his own death, revisits his youth as a spectator, and learns amid the forgiving wild strawberries (symbolic in Sweden of a favorite spot or sanctuary) that he had always denied desire.

Collaborators

- Victor Sjöström, Professor Isak Borg

- Gunnar Björnstrand, Evald Borg, Isak's son

- Ingrid Thulin, Marianne Borg, Evald's wife

- Bibi Andersson, Sara

- Folke Sundquist, Anders

- Björn Bjelfvenstam, Viktor

- Jullan Kindahl, Miss Agda, Isak's housekeeper

- Gunnar Sjöberg, Sten Alman, engineer

- Gunnel Broström, Berit Alman, Sten's wife

- Naima Wifstrand, Isak's mother

- Per Skogsberg, Hagbart Borg

- Per Sjöstrand, Sigfrid Borg

- Gio Petré, Sigbritt Borg

- Peder Hellman, Sigbritt's baby

- Gunnel Lindblom, Charlotta Borg

- Göran Lundquist, Benjamin Borg

- Maud Hansson, Angelica Borg

- Eva Möller, Anna Borg

- Lena Bergman, Kristina Borg

- Monica Ehrling, Birgitta Borg, Kristina's twin sister

- Yngve Nordwall, Uncle Aron

- Sif Ruud, Aunt Olga

- Gertrud Fridh, Karin, Isak's wife

- Åke Fridell, Karin's lover

- Max von Sydow, Henrik Åkerman

- Ann-Mari Wiman, Eva Åkerman, Henrik's wife

- Vendela Rudbäck, Elisabet, Isak's mother's helper

- Helge Wulff, Conferrer of doctor's degrees

- Ulf Johanson, Isak's father

- Harry Asklund, (Unknown part)

- Gittan Gustafsson, Art Director

- Björn Thermænius, First Assistant Cameraman

- Lennart Wallin, Boom Operator

- Gunnar Fischer, Director of Photography

- Sven Sjönell, Unit Manager

- Oscar Rosander, Film Editor

- Millie Ström, Costume Designer

- Aaby Wedin, Production Mixer

- Sven Persson, Re-recording Mixer

- Carl Axel Lundvall, Music Composer

- Johann Sebastian Bach, Music Composer

- Wilhelm Harteveld, Music Composer

- Herman Palm, Music Composer

- Erik Nordgren, Music Composer

- Göte Lovén, Music Composer

- Alwin Müller, Music Composer

- Eskil Eckert-Lundin, Orchestra Leader

- Allan Ekelund, Production Manager / Production Coordinator

- Gösta Ekman, Assistant Director

- Karl-Arne Bergman, Property Master

- Katinka Faragó, Script Supervisor

- Nils Nittel, Make-up Supervisor

- Louis Huch, Still Photographer

- Ingmar Bergman, Screenplay